Browse by category

- Adaptive reuse

- Archaeology

- Arts and creativity

- Black heritage

- Buildings and architecture

- Communication

- Community

- Cultural landscapes

- Cultural objects

- Design

- Economics of heritage

- Environment

- Expanding the narrative

- Food

- Francophone heritage

- Indigenous heritage

- Intangible heritage

- Medical heritage

- Military heritage

- MyOntario

- Natural heritage

- Sport heritage

- Tools for conservation

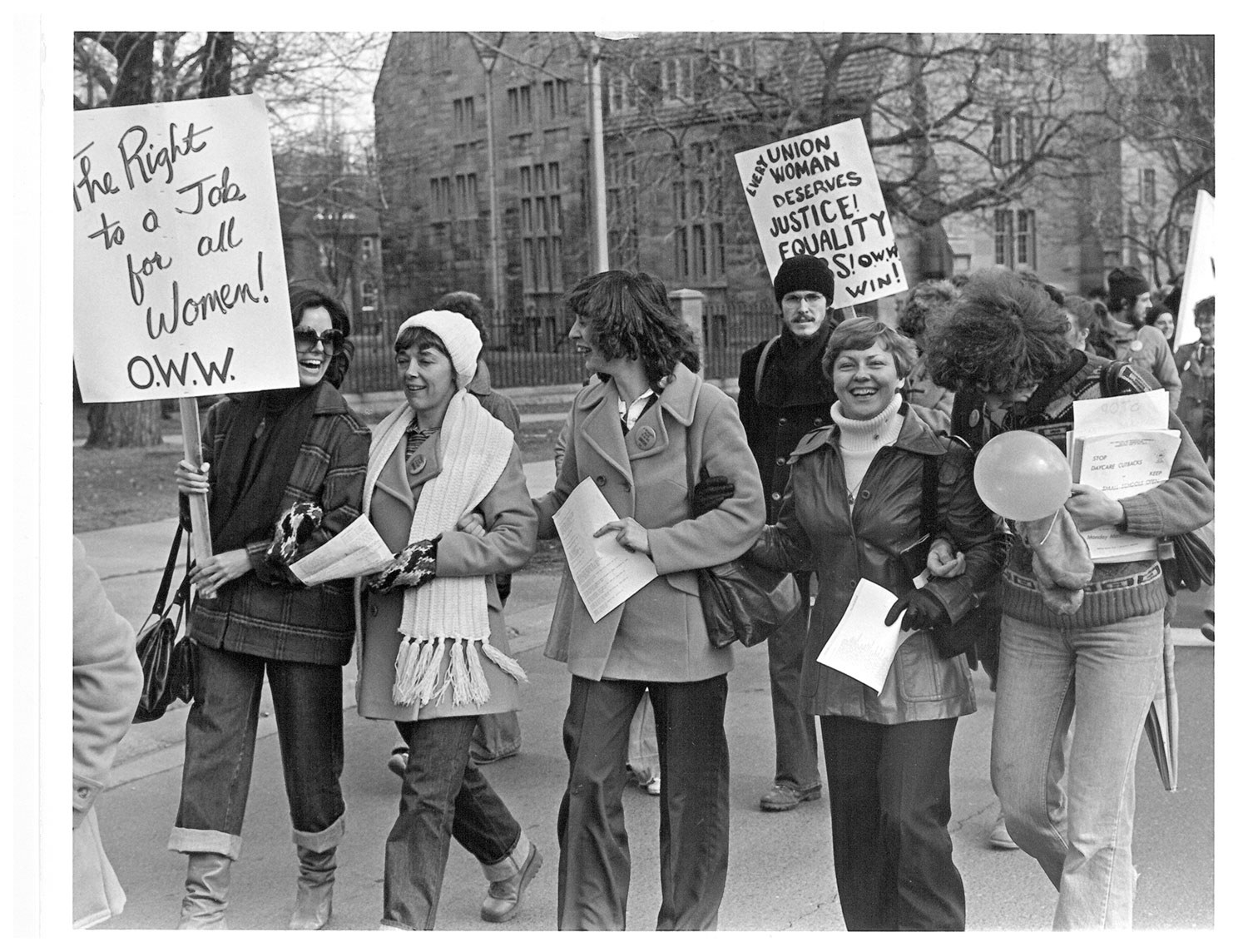

- Women's heritage

Women’s rights are human rights – The fight for an equal voice

"Women who are British subjects, 21 years of age, and who otherwise meet the qualifications entitling a man to vote are entitled to vote in a Dominion election. In effect January 1, 1919."

An Act to confer the Electoral Franchise upon Women, S.C. 1918, c. 20

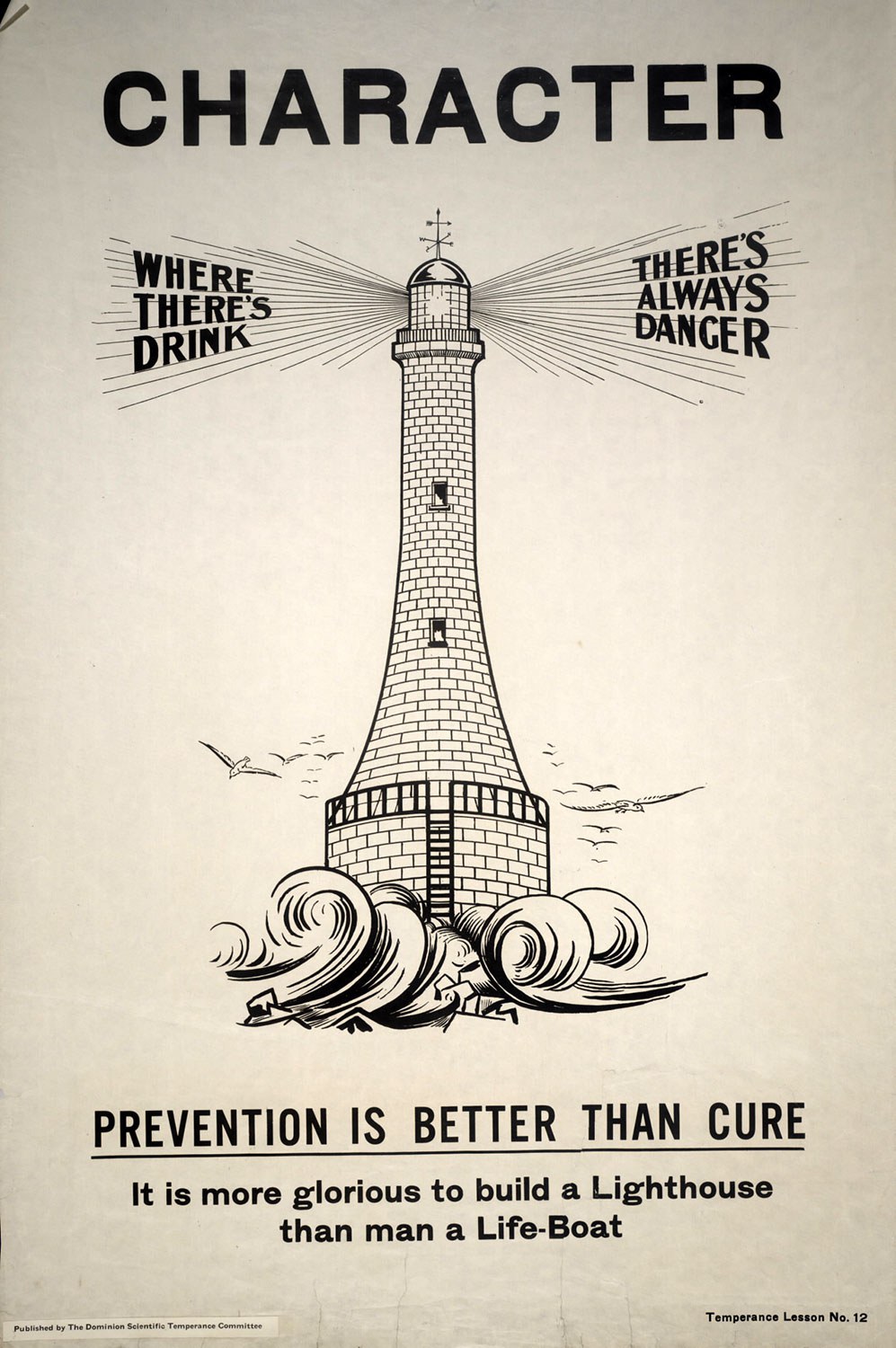

Did you know that women in Canada couldn’t vote in federal elections until 1918 – just 100 years ago? They could vote in some provinces prior to that – Manitoba was first in 1916, Ontario fifth in 1917 and Quebec last in 1940. And even then, this right only extended to property-owning British subjects over the age of 21. Did you known that Asian-Canadians were denied the right to vote until the late 1940s? Or that, under federal law, Indigenous women covered by the Indian Act couldn’t vote for band councils until 1951, and Indigenous people couldn’t vote in federal elections until 1960 – unless they gave up their status and treaty rights?

As a student at the University of Toronto in the late 1970s, I was deeply influenced by the feminist movement of the day, spurred on by an incident of gender discrimination in my teenage years that changed my understanding of the world around me. I’ve always been a feminist, passionate about women’s rights and human rights and about the need for people both to have and to use their voices. And still these dates surprise me. More surprising was the need for women to prove their right to be treated as persons under the law, but more on that later.

It isn’t possible in a few pages to summarize the history of women’s suffrage in Canada. I’d like to discuss some of the first advocates for women’s rights and women’s suffrage, the courageous women who led these movements, and to consider how far we’ve come since then.

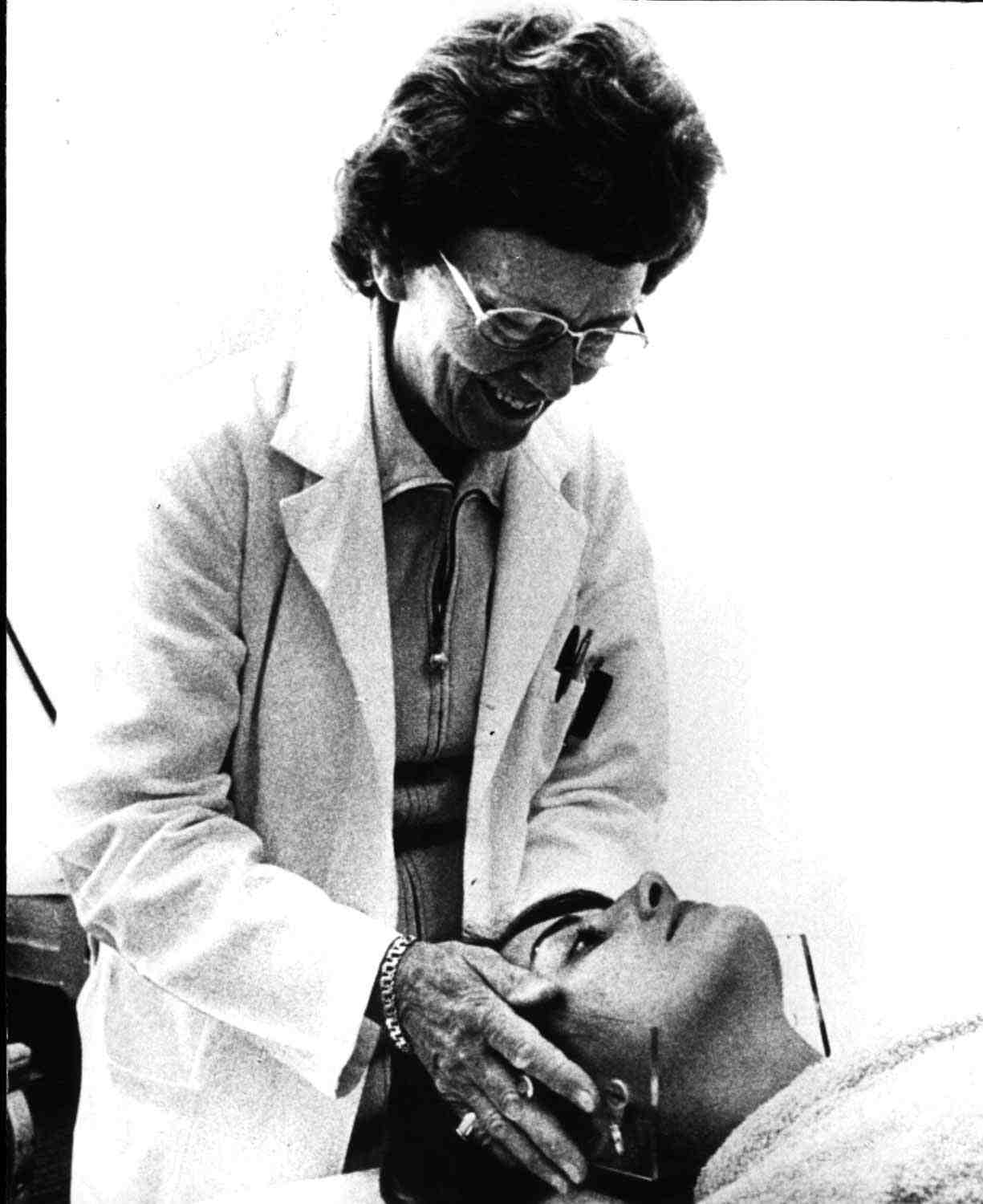

Imagine the experience of Emily Stowe, the first woman to be appointed principal of a public school in Ontario. She applied in 1865 and was denied entrance to the Toronto School of Medicine for the sole reason of her gender. In 1867, she obtained a degree from the New York Medical College for Women and returned to Canada, but it would be four more years before the University of Toronto admitted her and Jenny Trout to pursue their studies.

Dr. Stowe became a tireless advocate for women’s education and suffrage. She helped to establish the Toronto Women’s Literary Club “to form an association for intellectual culture, where they can secure a free interchange of thought and feeling that pertains to woman’s higher education, including her moral and physical welfare.” It became the Toronto Women’s Suffrage Club and, in 1903, the Canadian Suffrage Association, with Stowe as its first president.

The National Council of Women in Canada (NCWC), founded in 1893, was another voice lobbying to improve the status of women. At that time, only unmarried women and widows could vote in Ontario. Married women across Canada could neither own property nor hold public office.

Canadian suffragists at the end of the 19th century held national and international meetings, lobbied, circulated petitions and worked with male politicians who supported the cause. Ally Liberal John Waters, MPP of Middlesex North, introduced nine bills in favour of women’s suffrage from 1885-93. Suffragists also held mock parliaments, theatrical parodies that assumed that women had always held the right to vote and men were seeking enfranchisement. One such performance was held at the Horticultural Gardens in Toronto (now Allan Gardens) on February 18, 1896.

Sonia Leathes was a NCWC member who wrote a number of pamphlets advocating women’s suffrage, including “Where and How May Canadian Women Vote” (1911) and “What Equal Suffrage has Accomplished” (1911-12). In February 1914, University Magazine published “Votes of Women: Speech Given to the National Council of Women of Canada:” “Where women are not electors, parliament is not responsible to women, and their interests and wishes are not directly represented. Even when legislation is passed affecting the special interests of women … such laws are dealt with entirely as seems best to the representatives of the male electorate, and in no case are the women themselves consulted.”

This was a time of great change and upheaval in Canadian society. During the war years, women were called to serve in what were traditionally male roles in offices, factories and public service; they volunteered for home defence and service organizations and raised funds. Their contribution to the Canadian war effort and society as a whole was crucial. Coming out of that experience, women would no longer be ignored.

On April 12, 1917, female Ontarians obtained the right to vote in provincial elections. It would be 1943 before Ontario elected a female MPP to join the Legislature – Agnes Macphail and Rae Luckock both won that year and Macphail was the first sworn in.

Macphail had considerable experience by that time. On December 17, 1921, some 500,000 women voted for the first time in a federal election, which was won by Borden’s coalition government. Four women ran, and Agnes Macphail was elected to serve as Grey-Bruce MP, a position she held until 1940. Her first speech called for greater equality for women in Canadian legislation and society: “Mr. Speaker, women don’t want to be deemed to be part of the goods and chattel of men. Women want to be individuals as men are individuals. No more, no less – and I would like to see that principle embodied in law.” Following her defeat in 1940, Macphail was elected to the Ontario legislature in 1943 and 1948 and was responsible for Ontario’s first equal pay legislation, passed in 1951. At the time of her death in 1954, she was being considered for appointment to the Canadian Senate.

Appointment to the Canadian Senate was a significant issue. Until 1929, the government had argued that the power to “summon qualified Persons to the Senate” did not include women. In 1927, Emily Murphy, Nellie McClung, Irene Parlby, Louise McKinney and Henrietta Muir Edwards sought clarification from the Supreme Court of Canada as to whether the word “persons” in Section 24 of the British North America Act (1867) included “female persons.” The five male justices of the Supreme Court of Canada unanimously voted that it did not. The question was decided differently by the Privy Council of Great Britain in a case known legally as Edwards v. Attorney General of Canada, and more broadly as the Persons Case. When Lord Sankey, Lord Chancellor of Great Britain, announced their decision on October 18, 1929, he stated: “... to those who ask why the word [persons] should include females the obvious answer is why should it not?”

Prime Minister Mackenzie King appointed Cairine Wilson of Ottawa to the Senate in 1930. Twenty-three years passed before two more women were appointed to the Senate – Murial McQueen Fergusson and Nancy Hodges.

The Royal Commission on the Status of Women, chaired by Florence Bird, released its report in 1970. Its responsibility was to “inquire into … the status of women in Canada … to ensure for women equal opportunities with men in all aspects of Canadian society.” Among its conclusions: “The last 50 years, since woman suffrage was introduced, have seen no appreciable change in the political activities of women beyond the exercise of the right to vote. In the decision-making positions, and most conspicuously in the government and Parliament of Canada, the presence of a mere handful of women is no more than a token acknowledgement of their right to be there. The voice of government is still a man’s voice. The formulation of policies affecting the lives of all Canadians is still the prerogative of men.”

Following the work of the National Action Committee, the Canadian Advisory Council on the Status of Women was created in 1973 and, in the ensuing seven years, published studies, briefs and comments on such topics as human rights, criminal law, federal appointments and the rights of Indigenous women.

In November 1980, it submitted a brief on “Women, Human Rights and the Constitution” to the Special Joint Committee on the Constitution. It set out a series of recommendations focused on the proposed Charter of Rights and Freedoms.

The Charter of Rights and Freedoms of 1982 guaranteed rights and freedoms “equally to male and female persons” [s.28] and equal protection under the law [S.15]: “Every individual is equal before and under the law and has the right to the equal protection and equal benefit of the law without discrimination and, in particular, without discrimination based on race, national or ethnic origin, colour, religion, sex, age or mental or physical disability.”

The discussion continued through the work of a range of national and provincial commissions and organizations. In the 1980s, the National Action Committee on the Status of Women was a major voice in the Canadian women’s movement and a political advocate for women. The Native Women’s Association of Canada was founded in 1974; the Congress of Black Women of Canada was launched in 1975; Women’s Legal Education and Actions Fund was founded in 1985; the Canadian Women’s Foundation was created in 1991; and the National Council of Women of Canada continues its work, as do many other vital organizations.

Women have been fighting for generations to hold the same rights and privileges as men, to hold equal voice in decision making, equal status under the law. Where are women today in the political scene? According to Equal Voice – a national, multi-partisan organization dedicated to electing more women to political office in Canada – women continue to be underrepresented in every federal, provincial and territorial legislature in Canada. Only 26 per cent of elected members in Canada’s national Parliament, the House of Commons, are women – and women’s representation in provincial and territorial legislatures ranges from 9 to 37 per cent.

Clearly, there is still a lot of work to do. The #MeToo movement has brought to light the treatment of women that has always been unacceptable and will no longer be tolerated. Add current data from the Status of Women Canada that identifies the high rate of sexual violence against women as “one of the most pressing human rights issues facing Canadians today” and the horrific issue of missing and murdered Indigenous women. Even on issues of pay, Statistics Canada reports that women earn $0.87 for every dollar earned by men. How do we get to equality?

I take inspiration from the trailblazing women involved in this story and those featured on the pages that follow. They’ve broken through gender and racial barriers, faced opposition and ridicule. Each one has made a significant contribution, and none of their names should be forgotten.

I encourage you to learn more about the women and men who have fought for equality. I have some personal heroes – Kay Livingstone, Chief Elsie Knott, the Honourable Jean Augustine, Doris Anderson, Beverley McLachlin, Daphne Odjig, Jeanette Corbier Lavall, Roberta Jamieson, Roberta Bondar and Bertha Wilson. These women, and many more unsung heroes, have led and are leading the fight for equality for all women and working to make things better for generations to come. They are bold, sharp, insightful – building bridges, uniting us and making us optimistic for a better future. Who would you add to the list? And whose names will be added from our next generation?

As I look to that future, what I want for our sons and daughters, our grandchildren, great-nieces and nephews of all parts of society is a different #MeToo discussion. I want them to say equally: MeToo – I hold a seat in the House of Commons; MeToo – I’m a leader in the provincial legislature; I own an international corporation; I’m an entrepreneur, an artist, a parent, a teacher, a scientist, a doctor, a judge; MeToo – I am fulfilling my dreams; MeToo – my voice is being heard.

Photo: Almanda Walker-Marchand (c. 1928). Formed in Ottawa in 1914 at the outset of the First World War, the Fédération nationale des femmes canadiennes-françaises was the first francophone, secular society of women established outside of Quebec. Almanda Walker-Marchand served as its president for 32 years and saw the group expand from Ottawa to other parts of Ontario, the Prairies and British Columbia. Ph52-40. Université d’Ottawa, CRCCF, Fonds Fédération nationale des femmes canadiennes-françaises (C53).

![“Mayor Oliver: Wonder who told them we didn’t encourage the suffragette movement in Toronto?”, [photograph], ca. 1910, Newton McConnell fonds, C 301-0-0-0-996, Archives of Ontario.](https://www.heritage-matters.ca/uploads/Articles/Archives-of-Ontario-cartoon-I0007312-web.jpg)

![F 2076-16-3-2/Unidentified woman and her son, [ca. 1900], Alvin D. McCurdy fonds, Archives of Ontario, I0027790.](https://www.heritage-matters.ca/uploads/Articles/27790_boy_and_woman_520-web.jpg)

![Wyland, Francie. 1976. Motherhood, Lesbianism, Child Custody: The Case for Wages for Housework. Toronto: Wages Due Lesbians. Cover woodcut by Anne Quigley. CLGA collection, in monographs, folder M 1985-054].](https://www.heritage-matters.ca/uploads/Articles/Wages-Due-Lesbians_Wyland-pamphlet-image-web.jpg)