Browse by category

- Adaptive reuse

- Archaeology

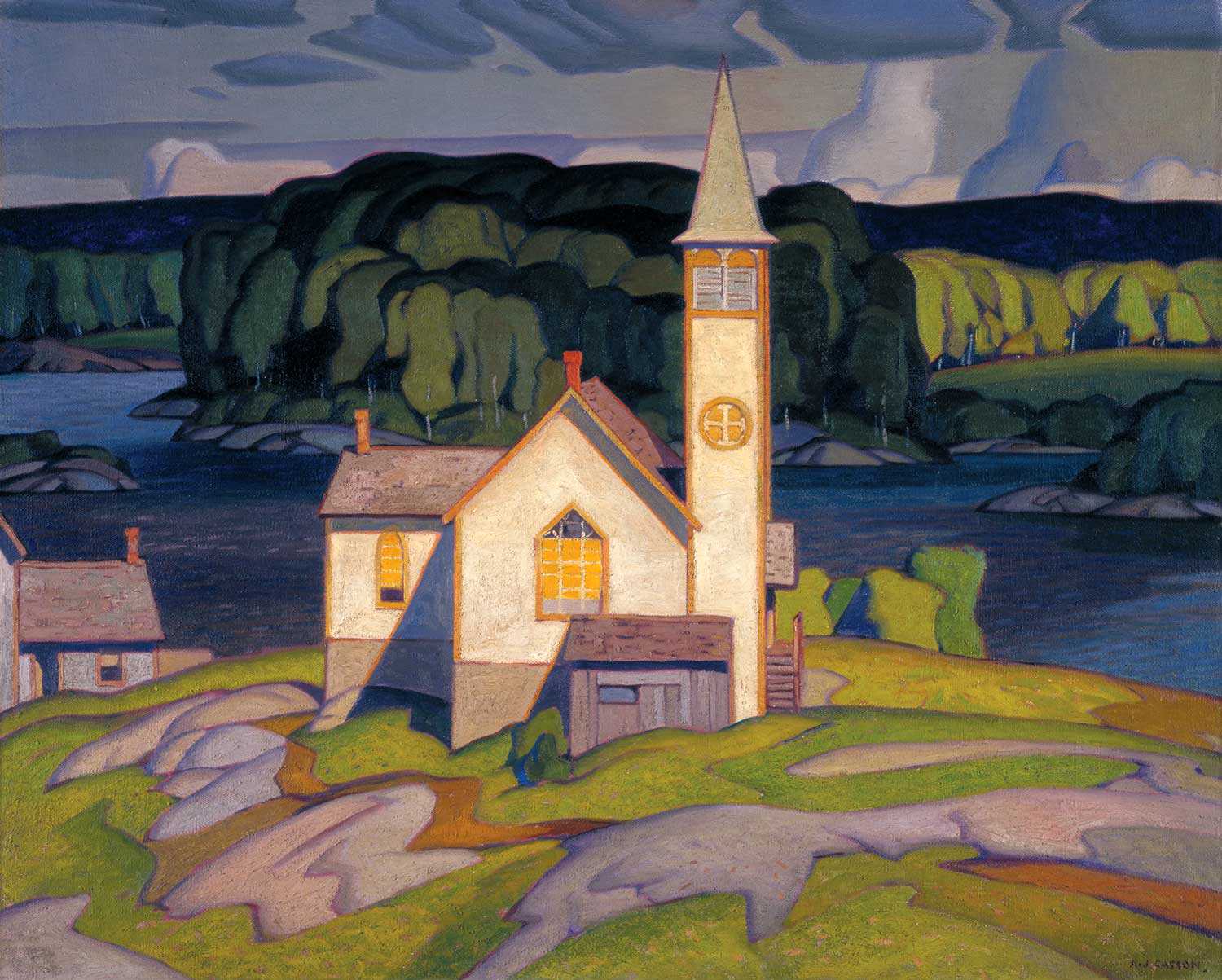

- Arts and creativity

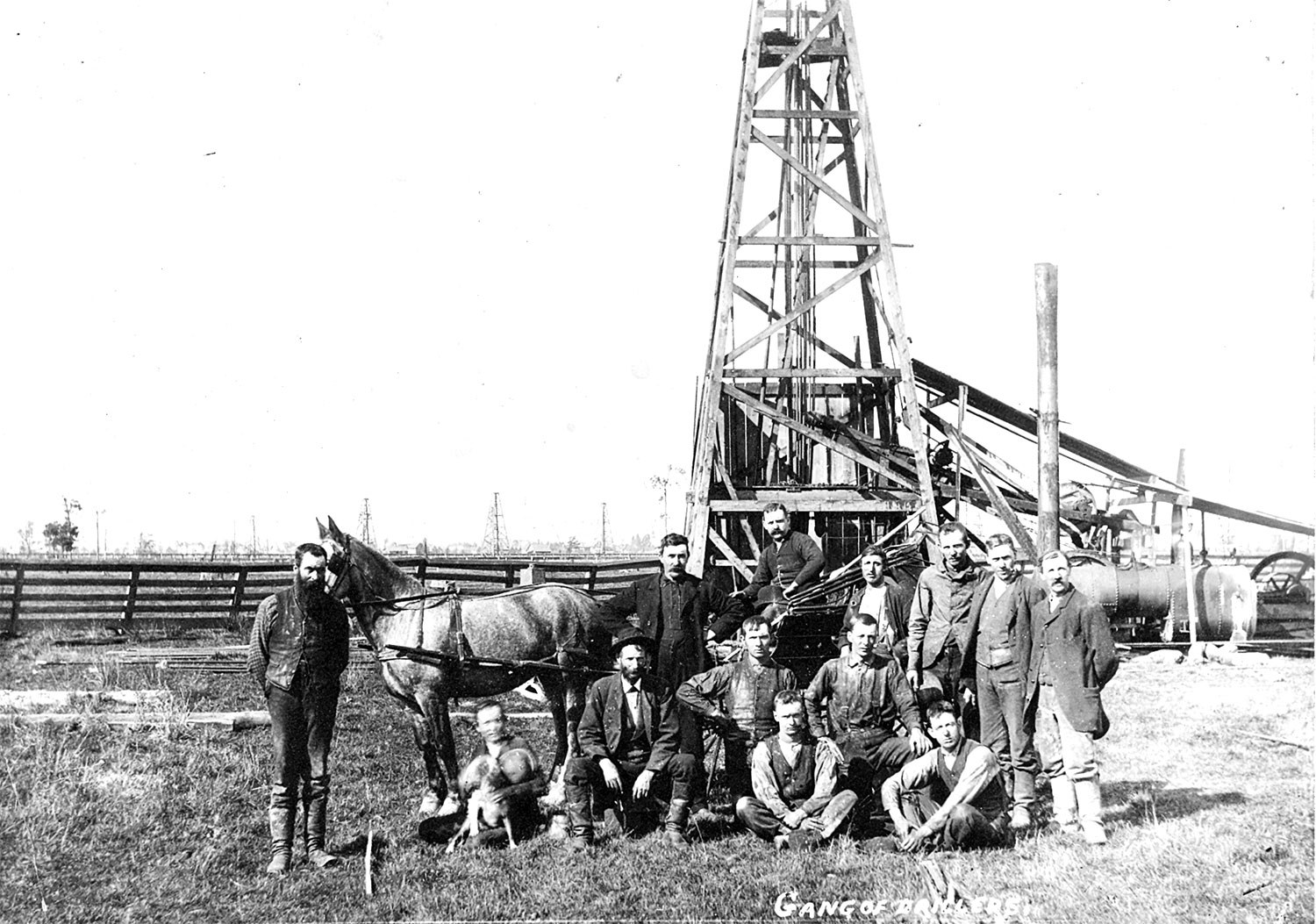

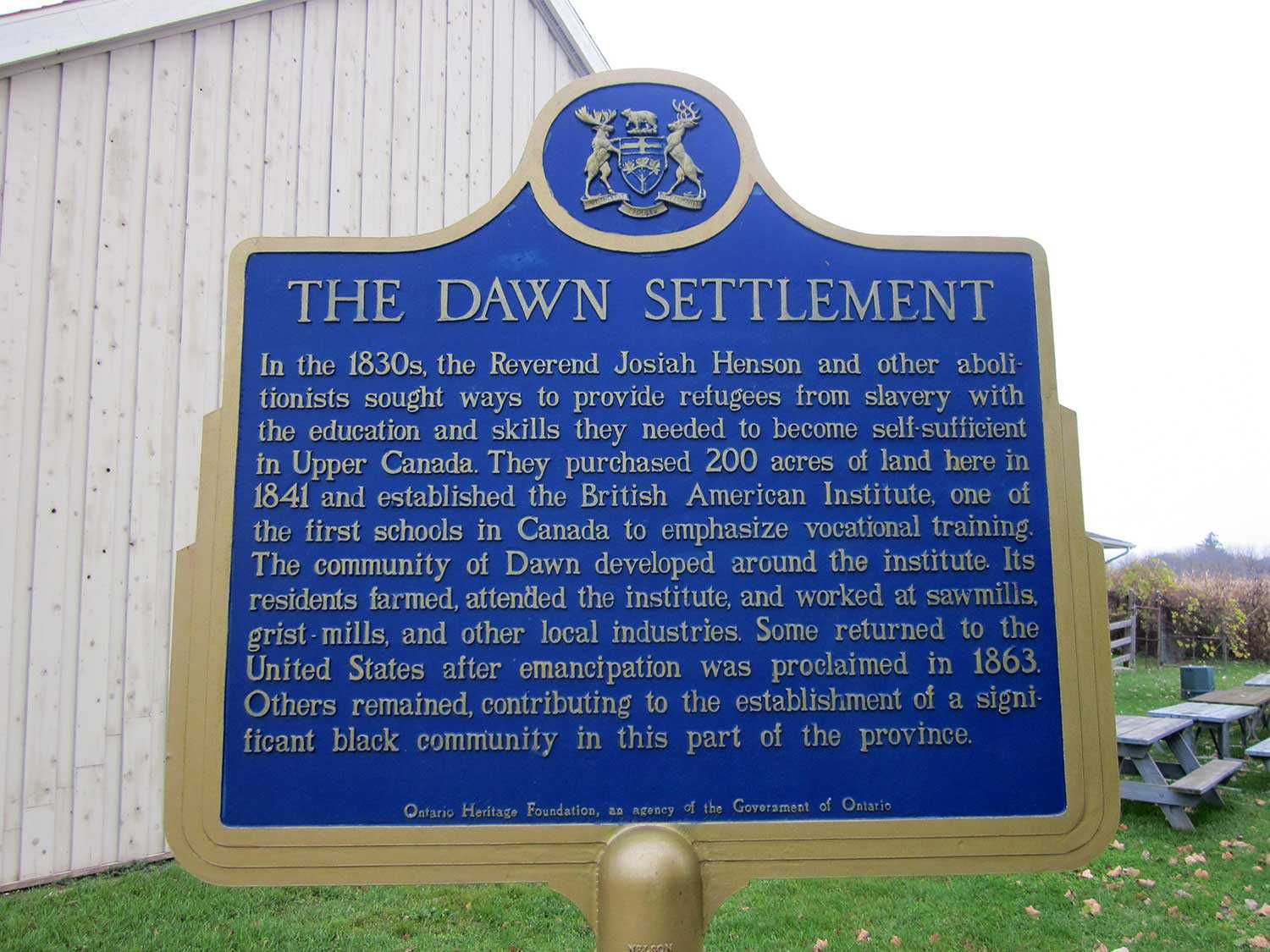

- Black heritage

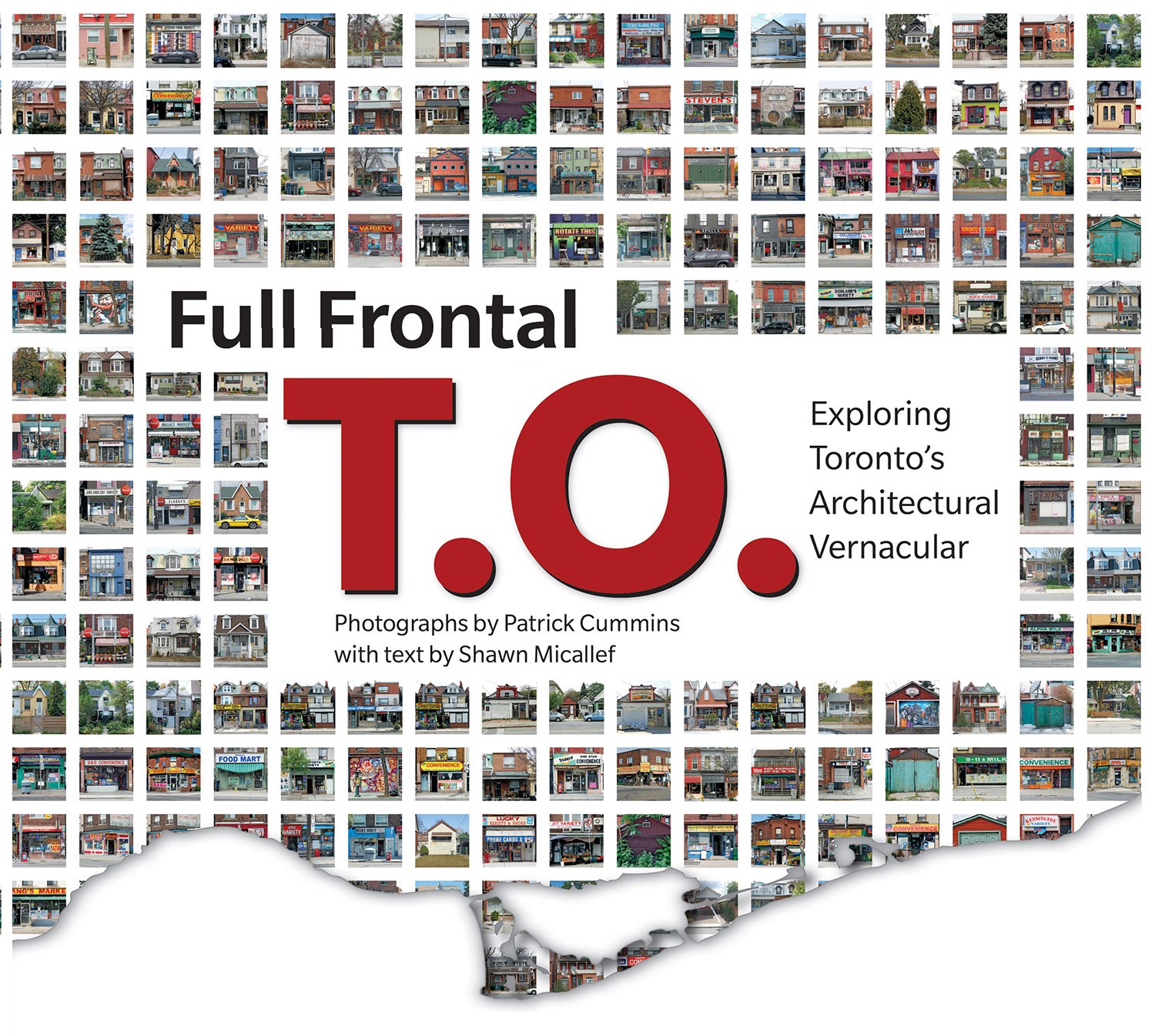

- Buildings and architecture

- Communication

- Community

- Cultural landscapes

- Cultural objects

- Design

- Economics of heritage

- Environment

- Expanding the narrative

- Food

- Francophone heritage

- Indigenous heritage

- Intangible heritage

- Medical heritage

- Military heritage

- MyOntario

- Natural heritage

- Sport heritage

- Tools for conservation

- Women's heritage

Revitalizing communities – The power of conservation

Published Date: 01 Oct 2019

Over the past few years, I’ve spoken and written extensively about value – exploring questions of what we protect, how we make those decisions, and who we involve in the decision making. The Trust team has been examining whose stories we tell, and whose heritage we protect through our sites and programs. We are working on expanding that narrative to a more honest, authentic and inclusive portrayal of Ontario’s heritage. These are important and timely discussions.

Beth Hanna is the Chief Executive Officer of the Ontario Heritage Trust.

In this issue of Heritage Matters, we turn our attention to a broader discussion of the value of heritage sites and old buildings in our communities. We are often asked to measure the impact of our work in economic terms. Funders, sponsors and governments are increasingly interested in how to measure heritage outcomes against metrics common in business ventures. What’s the bottom line? The return on investment? The highest and best use?

In fact, the economic impact of heritage revitalization is well documented. We know that investment in preserving and restoring old buildings creates jobs, stimulates business and tourism. We know that such investment supports small business and generates local economic activity. In this issue, we’ll examine the value of heritage conservation as a strong and necessary investment in the health and vitality of our communities.

The United States National Trust for Historic Preservation has examined three American cities as case studies to demonstrate the unique and valuable role that older, smaller buildings play in the development of sustainable cities. Older, Smaller, Better: Measuring how the character of buildings and blocks influences urban vitality (2014) concludes that “established neighborhoods with a mix of older, smaller buildings perform better than districts with larger, newer structures when tested against a range of economic, social, and environmental outcome measures.”

This report is worth examining in detail, not only for its key findings (which are summarized below) but also for the development and planning principles that it proposes for other communities to use. The key findings are:

- Older, mixed-use neighborhoods are more walkable

- Young people love old buildings

- Nightlife is most alive on streets with a diverse range of building ages

- Older business districts provide affordable, flexible space for entrepreneurs from all backgrounds

- The creative economy thrives in older, mixed-use neighborhoods

- Older, smaller buildings provide space for a strong local economy

- Older commercial and mixed-use districts contain hidden density

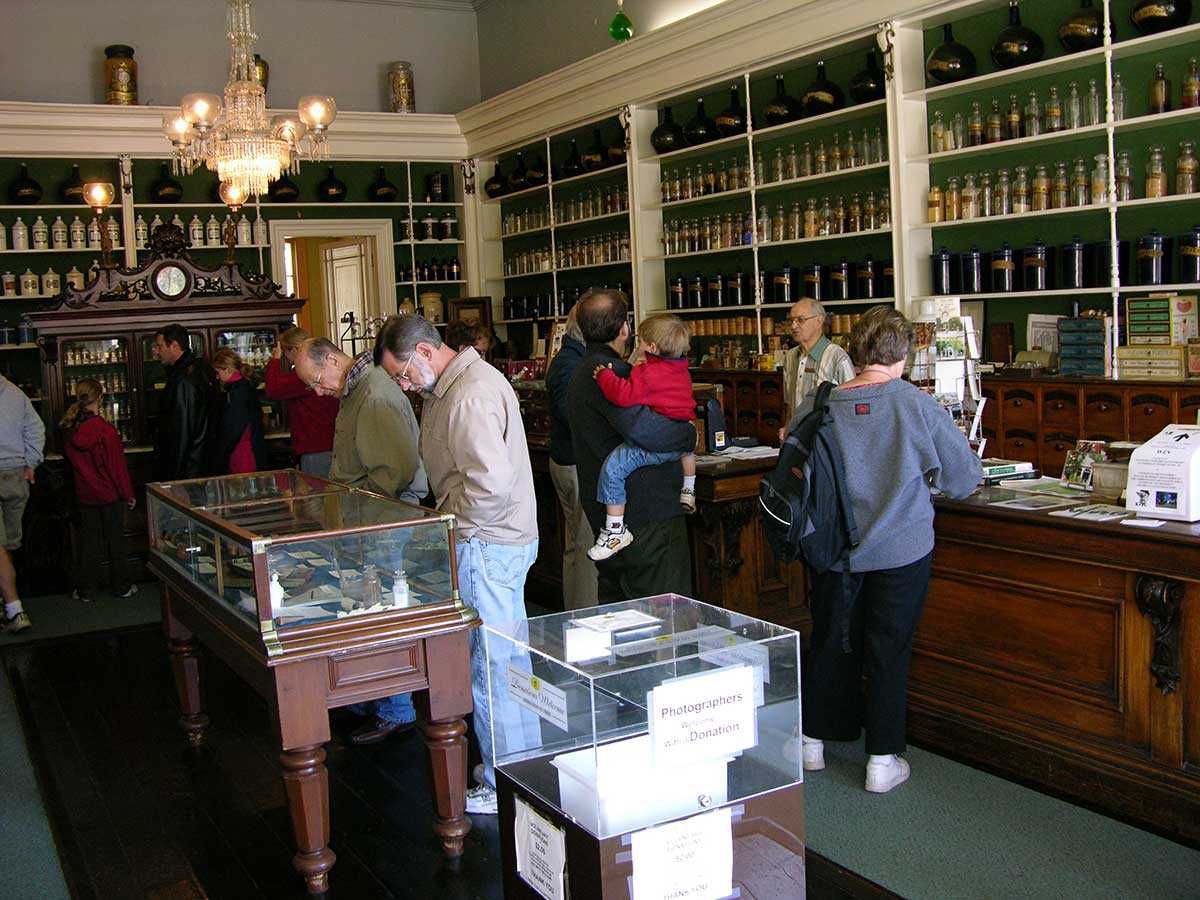

Heritage Counts 2018 is a study by Historic England of heritage buildings in commercial use in England. It found that there are 142,000 businesses operating in listed buildings across England, an increase of 18 per cent from 2012 to 2018; and, further, that 26 per cent of creative industries are located in conservation areas. It concludes that “the historic environment is one of the ‘capital stocks’ or ‘resources’ that businesses need to become established and to thrive.” It goes on to suggest that “Through careful economic development policies driven by conservation, and through engagement with communities and entrepreneurs, heritage assets can be a powerful contributor to the competitive advantage of place and to the social prosperity of local economies.” It is an important study that warrants careful review.

“Heritage assets have evolved and those that have survived have overcome functional obsolescence, neglect and even damage. They have adapted and continue to form the backbone of our local economies. Today the historic environment is host to many new and emerging sectors like creative industries for example – our research has shown that 26% of this growing sector is located in a conservation area.” Heritage Counts 2018, Historic England

The fact is that heritage conservation is more than an economic investment in our communities. Heritage preservation also contributes to their vitality, makes them more competitive and authentic.

Jane Jacobs, author of The Death and Life of Great American Cities, is well known for her commentary on cities, and for her conclusion that “new Ideas must use old buildings.” The full quote, of course, is: “Cities need old buildings so badly it is probably impossible for vigorous streets and districts to grow without them … for really new ideas of any kind – no matter how ultimately profitable or otherwise successful some of them might prove to be – there is no leeway for such chancy trial, error and experimentation in the high-overhead economy of new construction. Old ideas can sometimes use new buildings. New ideas must use old buildings.”

I wonder if she ever imagined how often she would be quoted in defence of conservation and of good urban planning.

“Cities need old buildings so badly it is probably impossible for vigorous streets and districts to grow without them.” Jane Jacobs, The Death and Life of Great American Cities

Heritage conservation is not just about the built environment. It is also about preserving historic spaces, landscapes, environmentally significant spaces, the relationship between people and the land. It’s about providing citizens with touch points that honour their places and their stories.

Max Page talks about historic preservation as being “fundamentally about bringing old places and living people into contact and dialogue.” ”Old places,” he says in Why Preservation Matters, “are powerful, and can spur our imagination, our emotions, our sense of connectedness in ways other connections to the past cannot.”

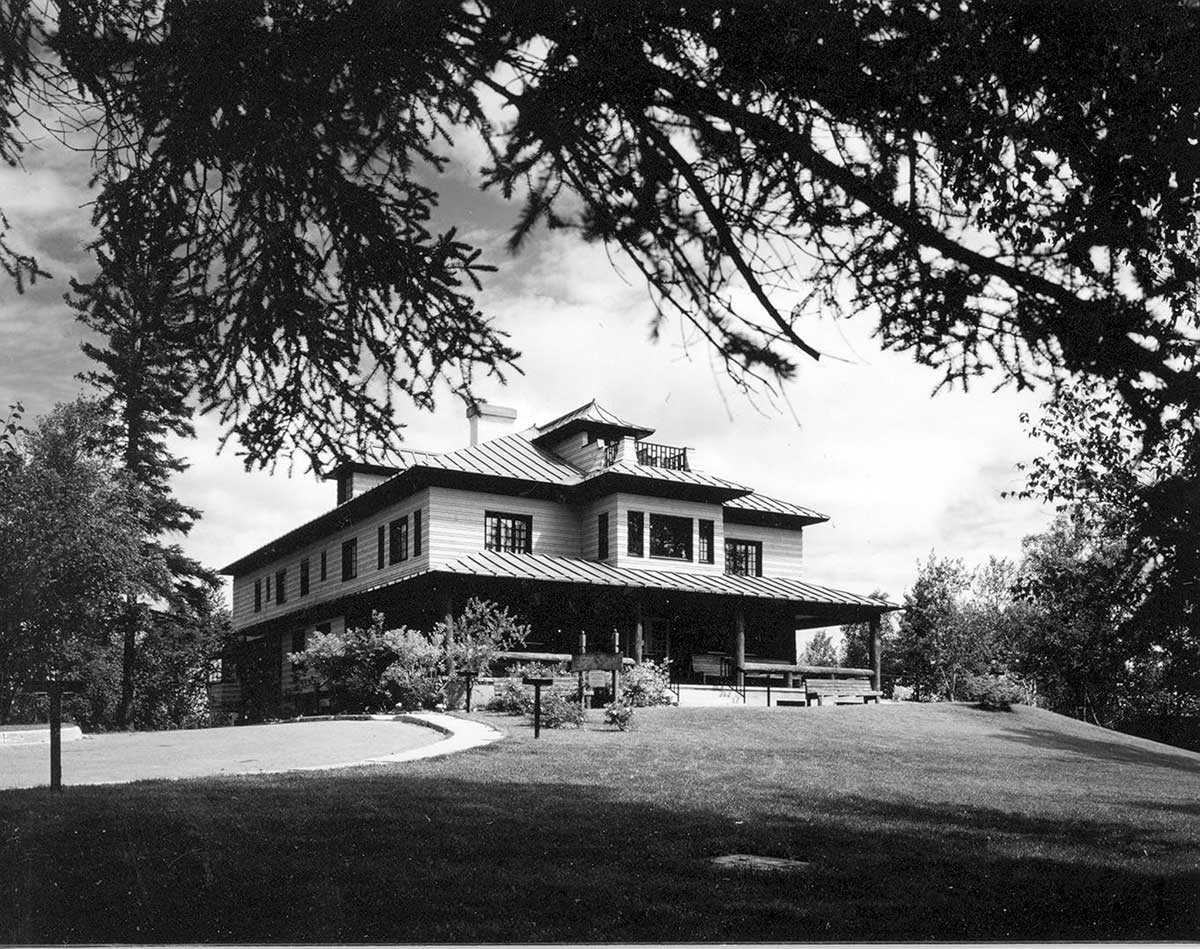

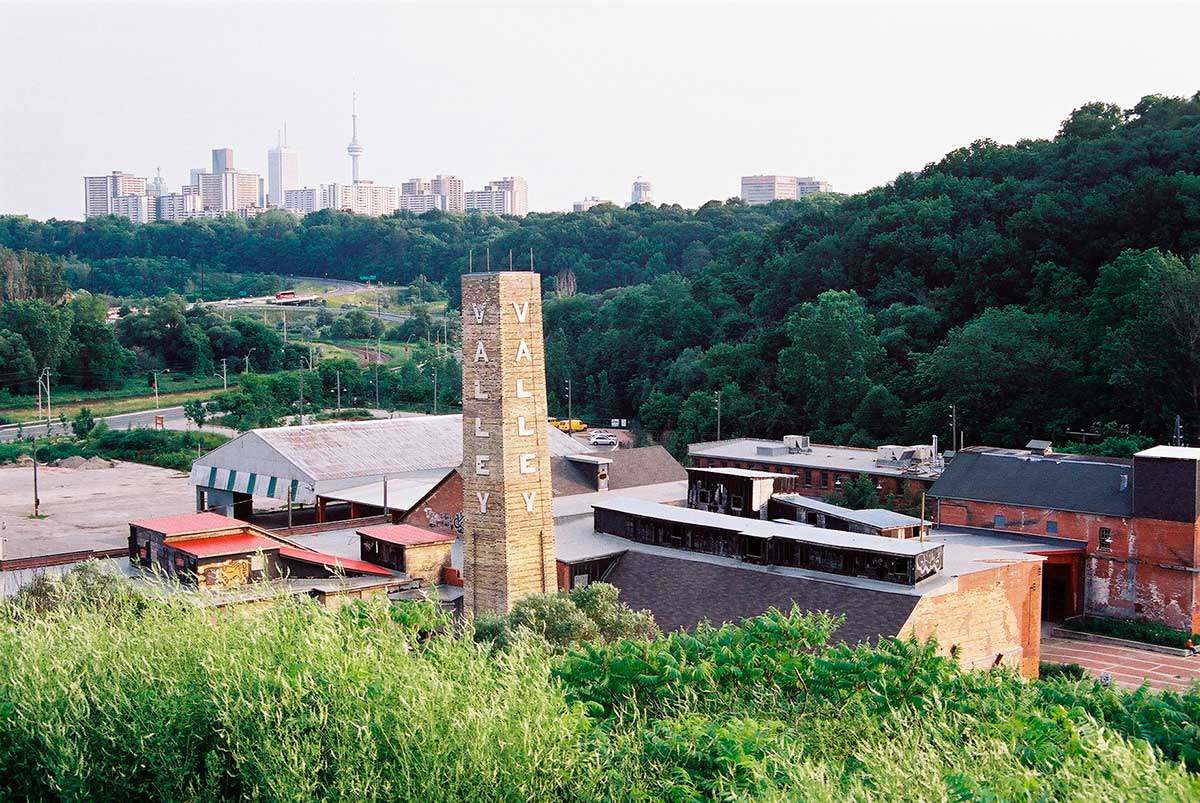

A great appetite exists across Ontario to visit, enjoy, shop at and dine in old places. Hills Strategies’ study Measuring the Economic Impacts of Heritage reported that the direct economic impact of arts, culture and heritage industries in Ontario in 2017 was $26.7 billion. Residents and visitors alike are seeking out and demanding that experience in places like Toronto’s Distillery District, Belfountain, St. Jacobs, the Rideau Canal and Agawa Canyon. It is hard to argue with that kind of commercial demand. But it takes vision, leadership and commitment to nurture these unique and commercially viable places in a competitive marketplace.

We see time and again examples of people with vision leading projects that realize positive results in their communities and neighbourhoods. The Lieutenant Governor’s Ontario Heritage Awards have recognized a number of these in recent years and I’d like to share just a few of many examples.

“As cities expand rapidly, conservation and continued use of heritage can provide crucially needed continuity and stability. A city’s conserved historic core can differentiate that city from competing locations thus helping the city attract investment and talented people. In addition, heritage anchors people to their roots, builds self-esteem, and restores dignity. Identity matters to all vibrant cities and all people. In other words, the past can become a foundation for the future.” Rachel Kyte, Vice President, Sustainable Development Network, The World Bank

In 2017, ERA Architects and Streetcar Developments won an Award for Excellence in Conservation for the conservation and revitalization of the Broadview Hotel in Toronto. Dating from 1891-92, the Broadview Hotel is a landmark building that serves as a community hub for the Riverside neighbourhood of Toronto. The team restored and maintained the key architectural elements of the building, while making strategic enhancements to allow for commercial and retail use. The result is the transformation of a landmark and the rejuvenation of the urban landscape in Riverside.

The Thames Talbot Land Trust is a non-profit organization dedicated to promoting and preserving ecological heritage and was the recipient of an Award for Excellence in Conservation in 2016. The organization purchased Hawk Cliff Woods, 93 hectares (230 acres) of culturally significant property. Through volunteer efforts, the Thames Talbot Land Trust launched several initiatives to preserve and enhance the Carolinian forest, which is along an international migratory route for birds and monarch butterflies. Due to these efforts, the site has been secured and opened for public enjoyment through marked trails and interpretive signage.

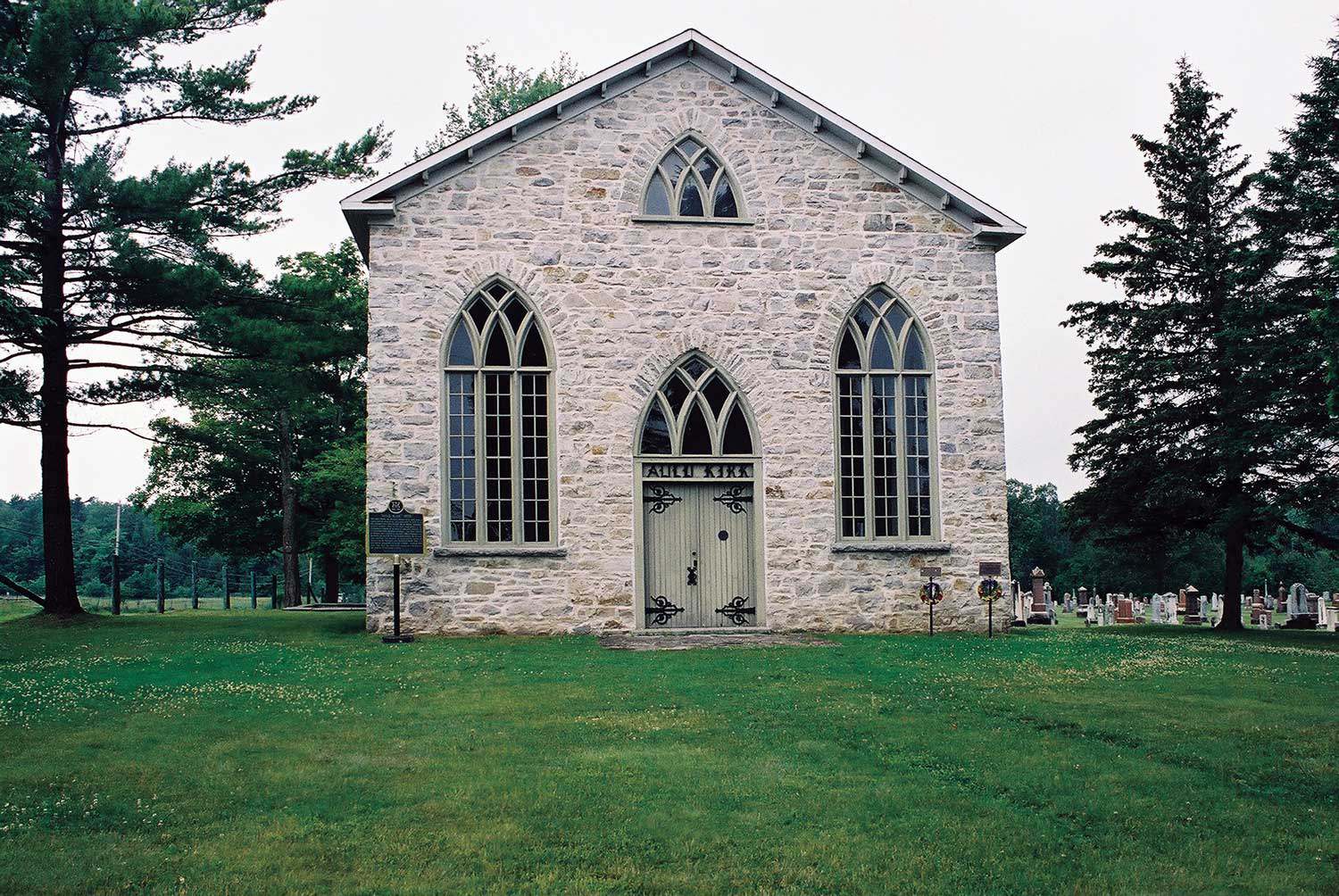

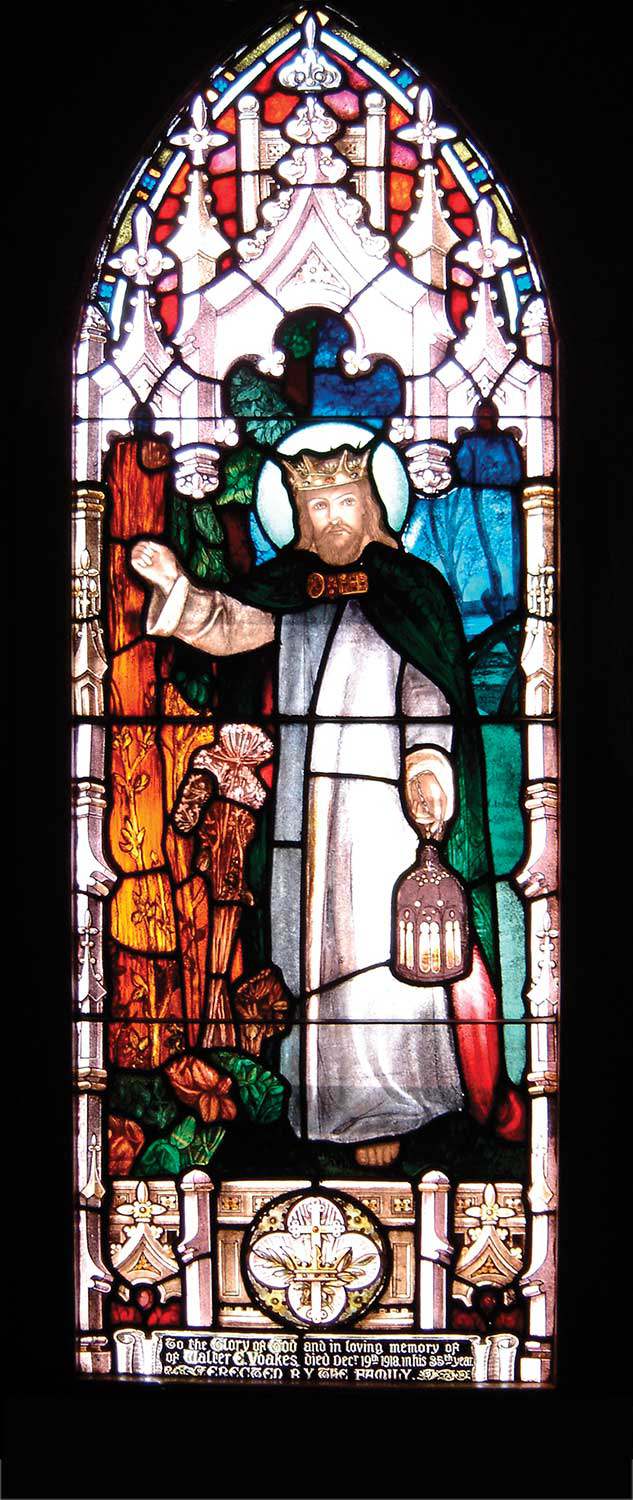

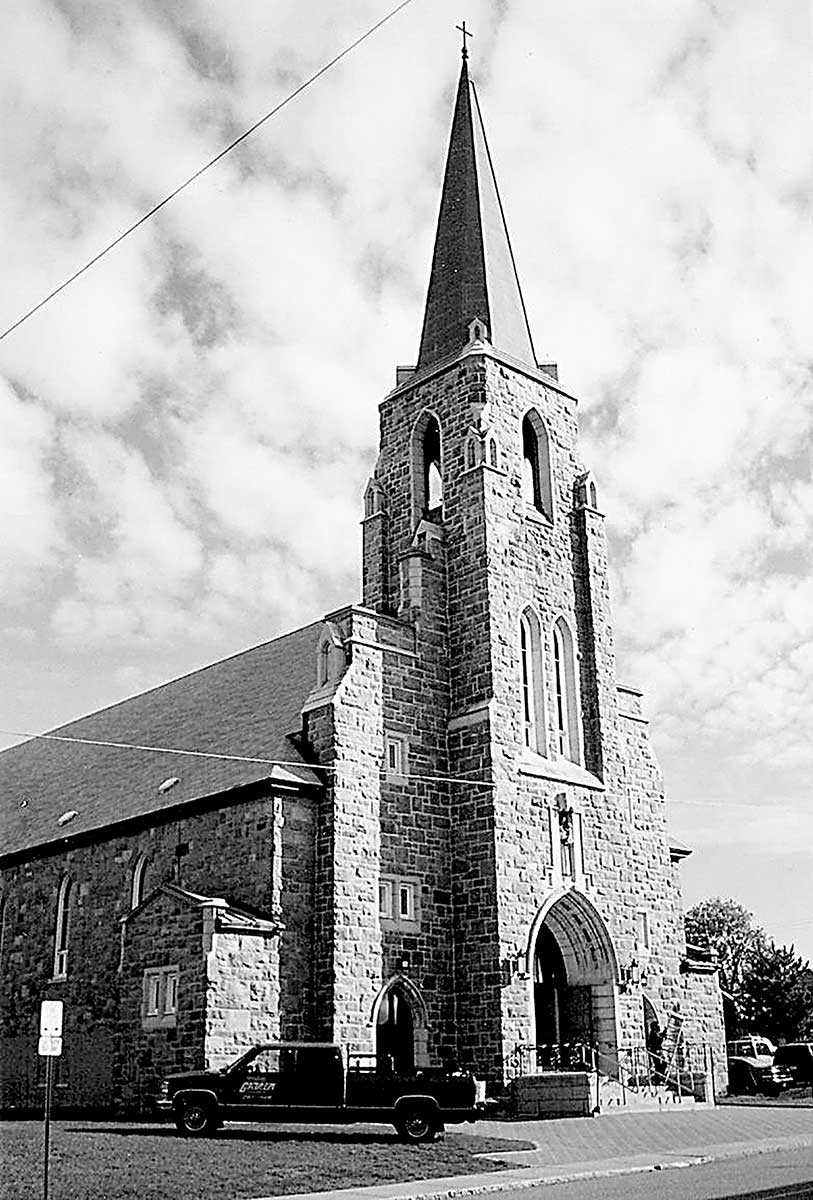

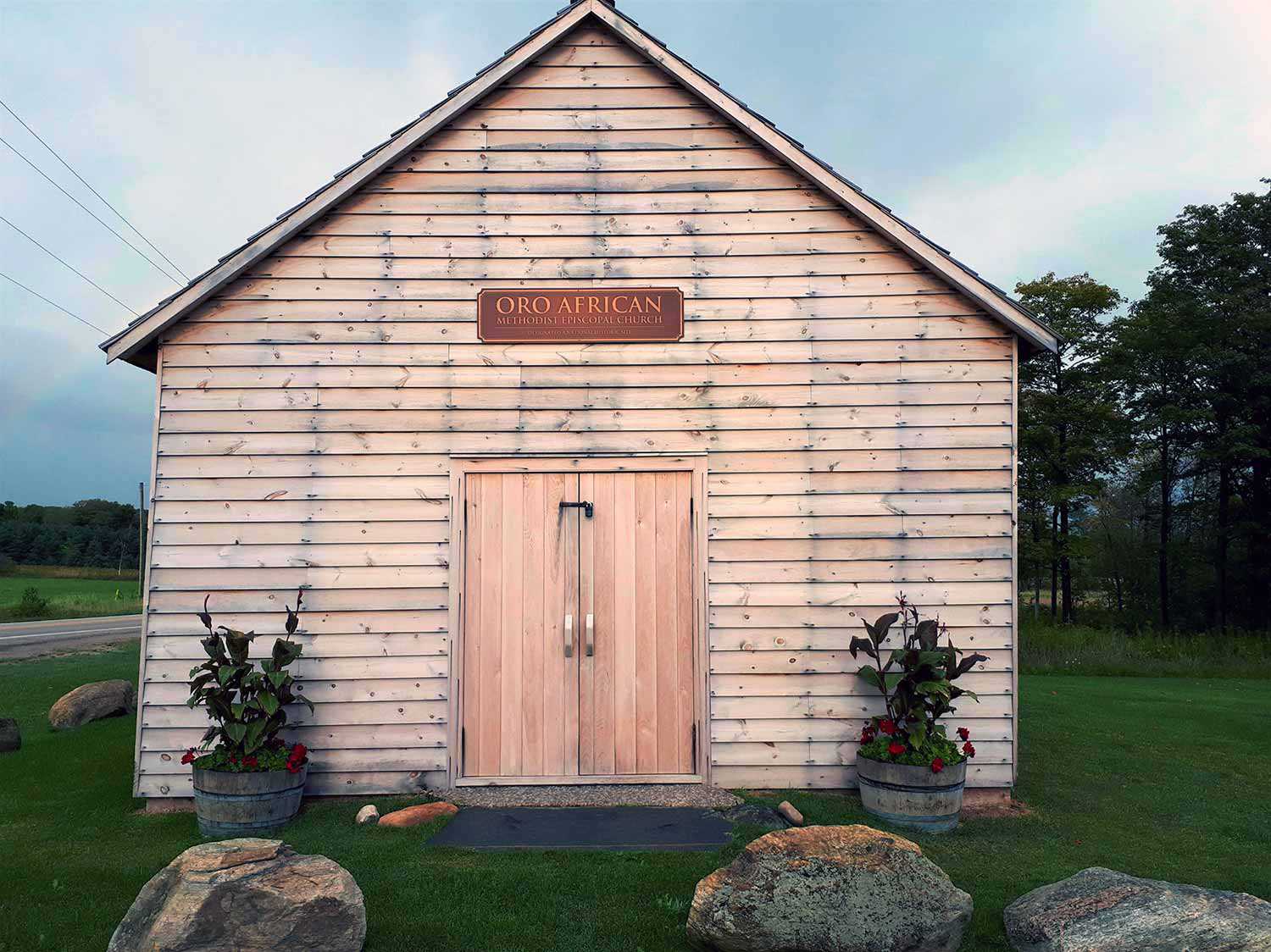

In 2015, the Township of Oro-Medonte launched an innovative crowdfunding and marketing campaign to save the Oro African Methodist Episcopal Church. The campaign was successful, not only for the funds that it raised to complete the restoration, but also for the unique excitement and passion that it generated throughout the community. The leadership demonstrated throughout all aspects of this campaign reached beyond Oro-Medonte, with a diversity of contributors and supporters from across Canada and the United States. The reopening event in August 2016 was symbolic of this celebration of cultural, religious and racial diversity.

And there are many others. The former Canadian Pacific Railway station in Owen Sound has a new life as Mudtown Station – a brewery, restaurant and community gathering place whose story you’ll see later in the magazine. The fire hall in Grimsby thrives as the Station 1 Coffeehouse. And the owner of Good Bread in Vittoria is adapting Norfolk County’s first Baptist church in a way that respects its landmark status in the community, recreates it as a community meeting place and will, once his vision is realized, offer both food and music, as well as truly delicious bread.

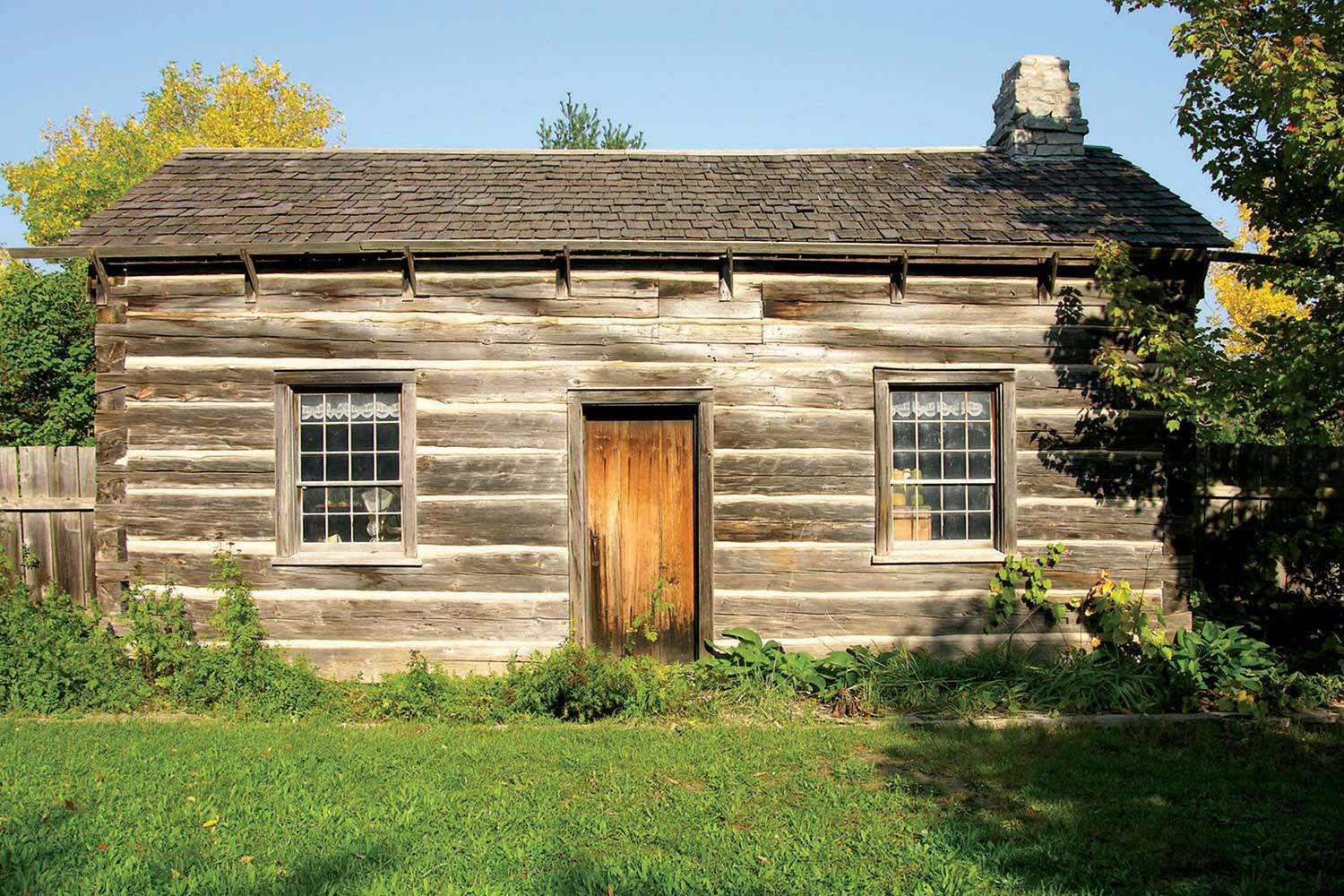

By investing in conservation, we are investing in giving new life to our neighbourhoods and showcasing the uniqueness and diversity of Ontario. Historic places play a key role in revitalizing and regenerating our towns, cities and rural areas. By protecting the historic environment, we provide citizens with touchstones to the past (the good and bad, beautiful and challenging), assess it from our present context, learn from it, and use it as a launch point to stimulate creativity and innovation.

![J.E. Sampson. Archives of Ontario War Poster Collection [between 1914 and 1918]. (Archives of Ontario, C 233-2-1-0-296).](https://www.heritage-matters.ca/uploads/Articles/Victory-Bonds-cover-image-AO-web.jpg)