Browse by category

- Adaptive reuse

- Archaeology

- Arts and creativity

- Black heritage

- Buildings and architecture

- Communication

- Community

- Cultural landscapes

- Cultural objects

- Design

- Economics of heritage

- Environment

- Expanding the narrative

- Food

- Francophone heritage

- Indigenous heritage

- Intangible heritage

- Medical heritage

- Military heritage

- MyOntario

- Natural heritage

- Sport heritage

- Tools for conservation

- Women's heritage

Realizing the dream: The discovery of insulin

Medical heritage

Published Date: Feb 12, 2016

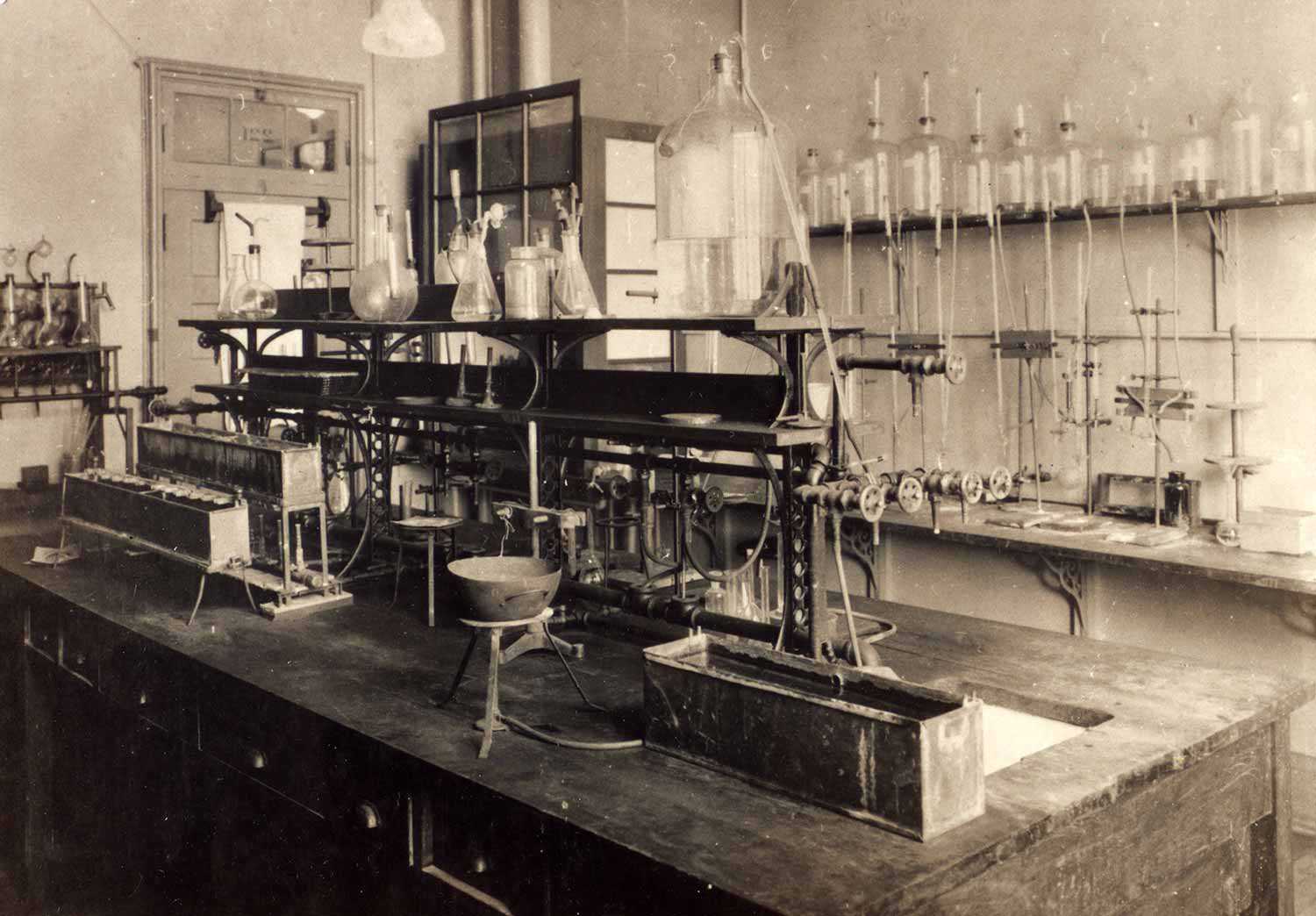

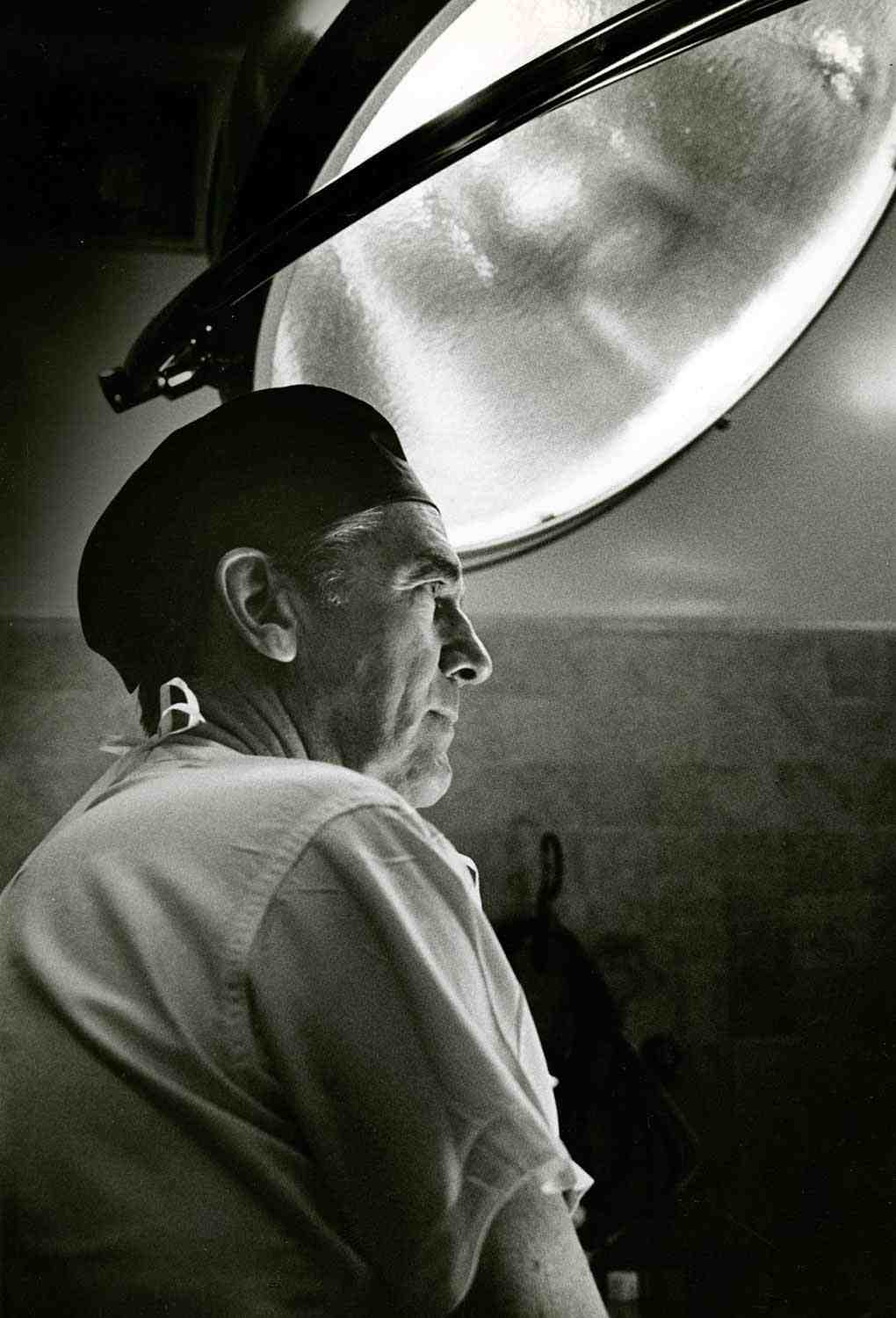

Photo: Photograph of laboratory 221 in the Old Medical Building, University of Toronto. This was the laboratory in which Banting and Best carried out some of their research in 1921-22. Courtesy Thomas Fisher Rare Book Library, University of Toronto. Banting Collection. P10043.

The news was stunning. Suddenly, in early 1922, researchers at the University of Toronto announced that they had discovered an effective treatment for diabetes mellitus. The team had isolated an internal secretion from the pancreas, which they named insulin. Injections of insulin erased all symptoms of diabetes from starved, dying victims of the disease, causing them to regain weight and strength. Insulin brought these patients – mostly children – back to life.

It still does. Tens of millions of sufferers from severe diabetes around the world maintain close-to-normal lives with their regular injections of insulin. Insulin was Canadian science’s greatest gift to humanity.

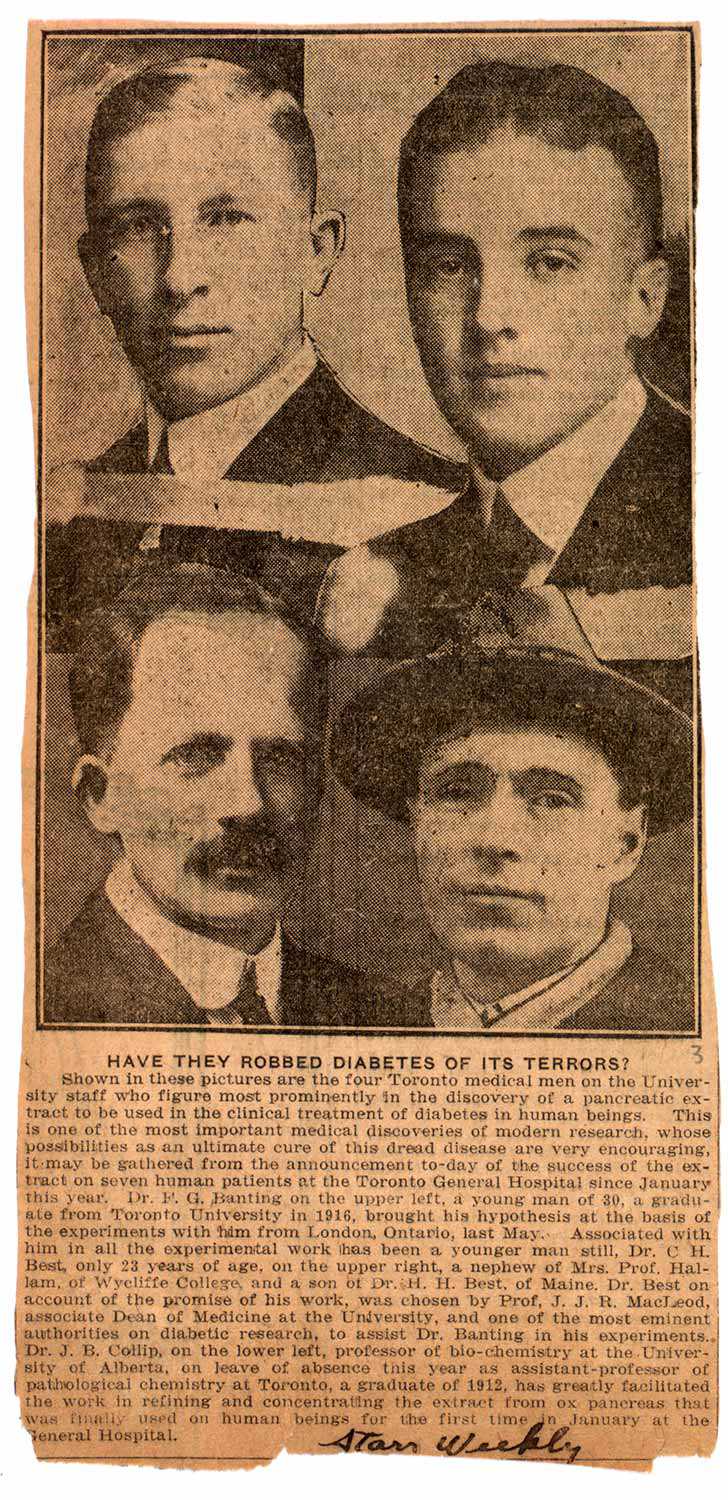

Toronto Star weekly newspaper clipping of March 26, 1922 shows (from top left, clockwise) Frederick Banting, Charles H. Best, James B. Collip and J.J.R. Macleod. This photograph collage was reprinted in several Canadian newspapers. Courtesy Thomas Fisher Rare Book Library, University of Toronto. Banting Collection. C10025.

In October 1923, the Nobel Prize was awarded to Drs. Frederick Banting and John J.J.R. Macleod for the discovery of insulin. This was the quickest honouring of a discovery in Nobel history, and remains Canada’s only Nobel Prize in physiology or medicine.

Banting, who had had the idea that prompted the insulin research to begin under Professor Macleod’s supervision in the physiology department at the University of Toronto, announced that he would split his share of the prize money with his student assistant, Charles Best. Macleod shared his money with a biochemist who had been added to the team, James B. Collip.

For many years, there was much puzzlement and controversy about how the credit for the discovery of insulin should be allocated. Most Canadians, and many others, came to believe that insulin had been discovered only by Banting and Best, working on their own and only getting some vague help in the later stages from Macleod and Collip. But once the full documentary record of the insulin research became available, it became evident that Banting and Best had only started a ball rolling – Macleod had indicated the directions in which it should roll, and Collip had supplied the final push to achievement. Discovering insulin had been a collaborative effort, involving at least four scientists.

Working as a team at the University of Toronto, an institution newly equipped to support advanced research, was key to their achievement. The background story to the coming of insulin was the way in which the people of Toronto, Ontario and Canada had come to believe in the importance of research in the early years of the 20th century. They had decided that Ontario’s provincial university should develop the capacity to conduct world-class experimentation and that Canada should be on the frontier of modern science, contributing to discovery and progress.

Governments, alumni and philanthropists had poured resources into building the University of Toronto’s physical and intellectual research capacity. Thus, when Frederick Banting, a practising physician, took a crude idea to do some research into diabetes back to his alma mater, he was welcomed and supervised by an internationally renowned expert in carbohydrate metabolism, Macleod. He was given talented assistance by a brilliant science graduate, Best. And then he was pulled to victory by the extractive wizardry of a visiting biochemist, Collip.

The team had all the research animals and other resources that they needed to carry out their experiments. Insulin emerged in Canada because the University of Toronto was the first research facility to assemble the expertise and resources necessary to stage an all-out assault on this problem.

“If you build it, he will come,” says the voice in the classic movie Field of Dreams. In the early years of the 20th century, Ontario’s and Canada’s leading university had been redirected to become a field of medical dreams, where it was hoped that great things might happen. Almost unbelievably – you’d think it had been scripted – Banting came up with his idea, and a great research game was played with amazing success.

The real beneficiaries, of course were not particularly interested in the scientists’ struggles for credit. They just wanted to celebrate their good fortune in having access to one of the greatest and most dramatic breakthroughs in the history of medicine. As a wise physician said at Toronto’s Nobel dinner in 1923, “In insulin, there is glory enough for all.”