Browse by category

- Adaptive reuse

- Archaeology

- Arts and creativity

- Black heritage

- Buildings and architecture

- Communication

- Community

- Cultural landscapes

- Cultural objects

- Design

- Economics of heritage

- Environment

- Expanding the narrative

- Food

- Francophone heritage

- Indigenous heritage

- Intangible heritage

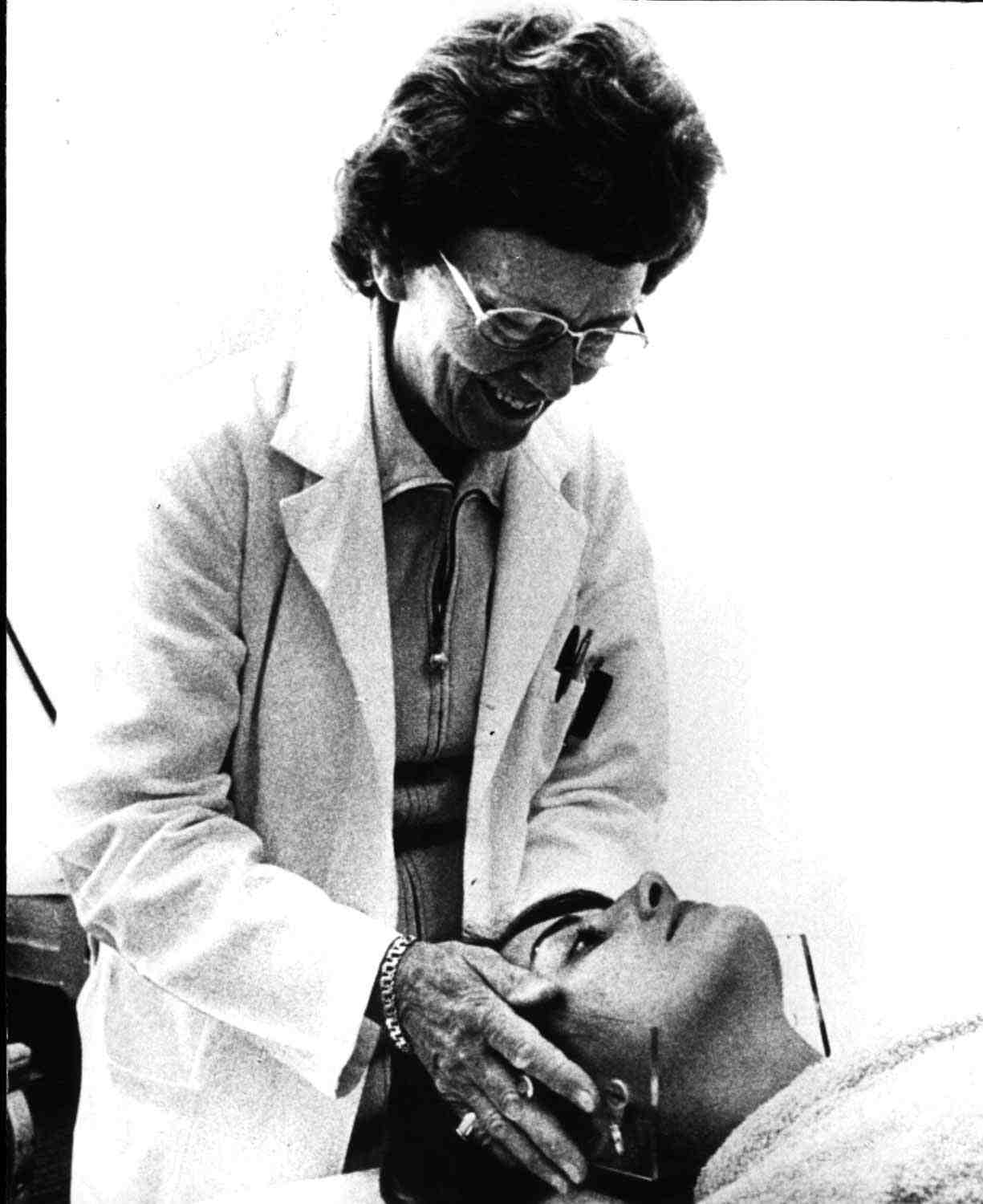

- Medical heritage

- Military heritage

- MyOntario

- Natural heritage

- Sport heritage

- Tools for conservation

- Women's heritage

Practices and attitudes die slowly: Sexual assault legislation and activism in Canada

In 1967, during a decade of social change and revolution, the federal government launched the Royal Commission on the Status of Women to address the growing feeling that progress on gender equality had stalled. They aimed to provide practical solutions that the government could implement to ensure that all Canadians had equal opportunities. Their 1970 report identified crucial areas where changes were needed – including family law, income inequality, lack of political representation and the Indian Act. It poignantly noted that, “The stage has been set for a new society equally enjoyed and maintained by both sexes. But practices and attitudes die slowly.” This 50-year-old observation continues to resonate for activists working for women’s equality, especially those involved in the fight against sexual violence.

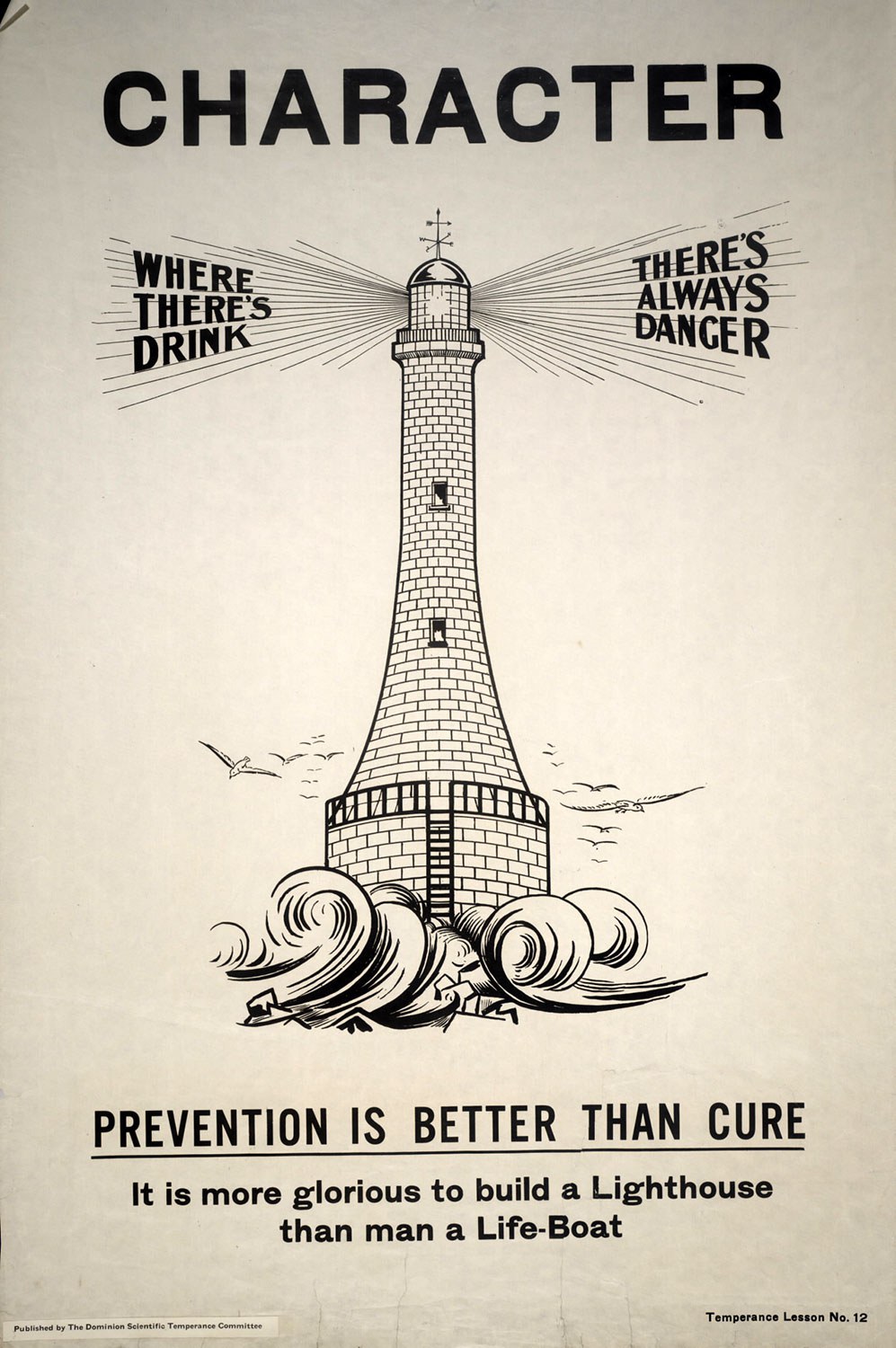

For most of Canadian history, it was difficult for women to press charges for sexual assaults. Survivors of sexual assault were thought to be unreliable and untrustworthy witnesses. Their testimonies were not considered sufficient evidence to prove that a crime had occurred; the prosecution either had to provide independent evidence or another witness. This hurdle made it almost impossible to try most sexual assault cases. In the 1970s, women’s organizations, legal professionals and academics began to place increased pressure on the federal government to reform sexual assault laws to reflect the seriousness of these crimes.

In 1983, Canada’s legal system began to catch up with these demands. Bill C-127 reformed sexual assault legislation to broaden the definition of sexual assault, including removing an exemption for spouses. It included legal changes to value survivors’ testimonies. The federal government of the time hoped that these changes would increase conviction rates and help reduce the shame and stigma that survivors of sexual assault faced when they came forward. Trying and convicting sexual assault cases, however, continues to be a challenge in the Canadian legal system. Many survivors of sexual assault still experience obstacles reporting these offences to authorities and getting resolutions to their cases.

In spite of gains that women have made in society, the risk of sexual violence continues to impact their lives. Additionally, 60 per cent of students enrolled in post-secondary schools are women. Yet, women’s increased presence on campus has not made schools safe places for women. Approximately one in five students will experience some form of sexual assault while they are attending university or college, but schools have struggled to resolve complaints that they receive about sexual harassment and violence experienced on campus. In the last five years, these experiences have led students and advocacy organizations to voice their frustration at a system that never seems to be improving. In Ontario, this outcry led to the mandatory implementation in 2017 of sexual assault policies at all postsecondary institutions. Once these policies have become an established part of campus culture, they aim to reduce the likelihood that students will have to worry about their personal safety on campus and enable them to contribute to the shaping of a more positive culture for dealing with sexual violence on campus.

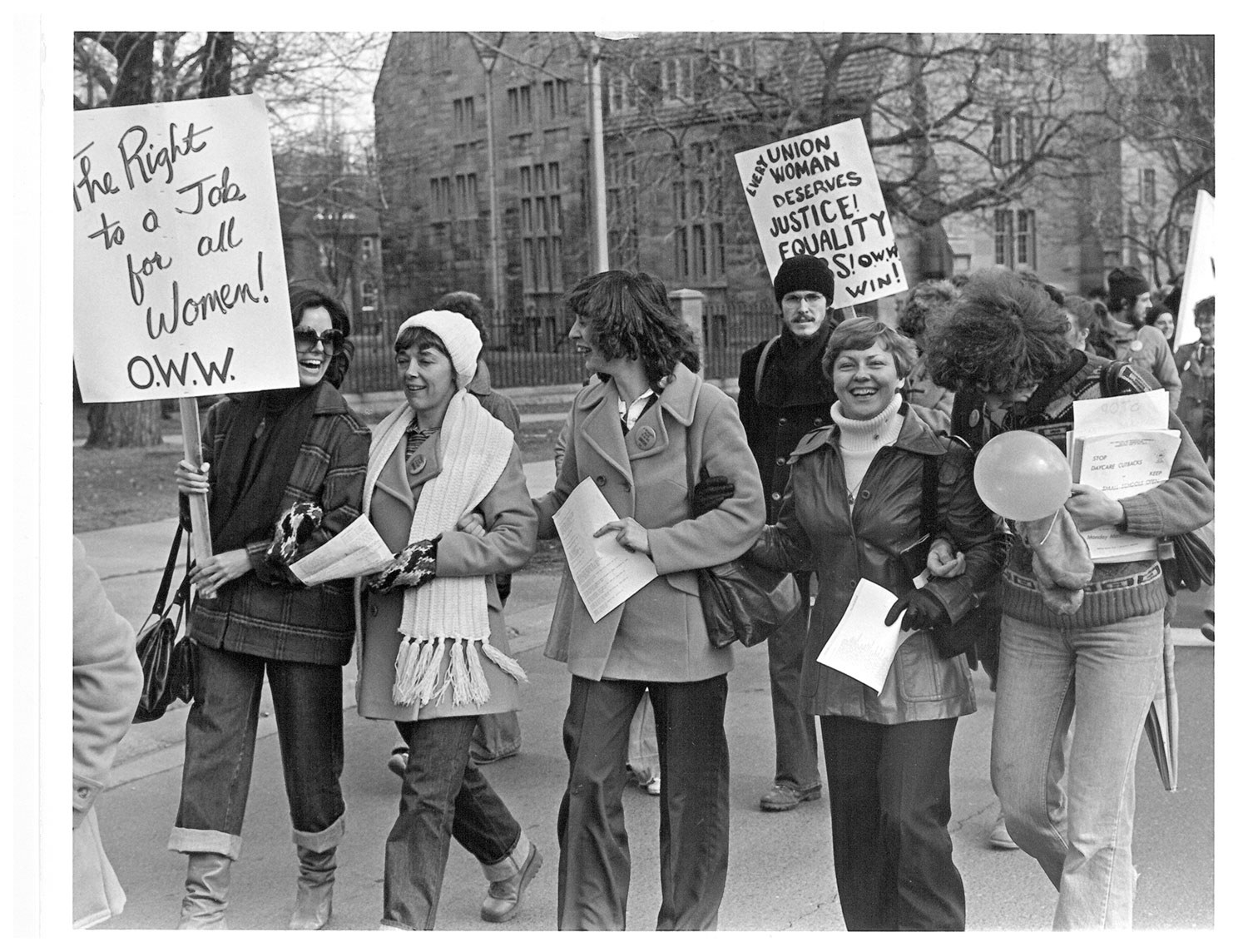

As legislative changes slowly occurred, women across Ontario realized that collective action was integral to making their voices heard on a national scale. Despite some gains, women were still underrepresented in legislatures and the House of Commons, and lacked the numbers to raise awareness for topics like sexual assault. Take Back the Night Marches provided women with an opportunity to raise awareness, find support and voice their frustration with the continued violence that women faced in society. These gatherings began in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania in 1975 after the murder of a young woman walking home alone at night. In 1981, the Canadian Association of Sexual Assault Centres agreed to hold marches across Canada that September. These marches became powerful spaces where women could support each other and raise community awareness about the continued prevalence of sexual assault and violence against women in communities. Take Back the Night marches are still held in cities across Ontario – from Windsor to Thunder Bay.

Canadian women continue to be active in standing up in international solidarity for equality and defence of human rights. On January 21, 2017, people in Canadian cities and towns joined in the Women’s March. Toronto’s march was the largest in the country, with over 60,000 protestors converging on Queen’s Park and Nathan Phillips Square. (On January 20, 2018 Women’s Marches were held in 38 communities across Canada, a 20 per cent increase over the number held in 2017.) This meaningful support for the continued advancement of gender equality and against oppression demonstrated that while the struggle for gender equality is not yet over and remains a powerful force to be reckoned with. The stage is still set for a society equally enjoyed by everyone, and through activism and solidarity we may hope that other practices and attitudes will finally die off.

![“Mayor Oliver: Wonder who told them we didn’t encourage the suffragette movement in Toronto?”, [photograph], ca. 1910, Newton McConnell fonds, C 301-0-0-0-996, Archives of Ontario.](https://www.heritage-matters.ca/uploads/Articles/Archives-of-Ontario-cartoon-I0007312-web.jpg)

![F 2076-16-3-2/Unidentified woman and her son, [ca. 1900], Alvin D. McCurdy fonds, Archives of Ontario, I0027790.](https://www.heritage-matters.ca/uploads/Articles/27790_boy_and_woman_520-web.jpg)

![Wyland, Francie. 1976. Motherhood, Lesbianism, Child Custody: The Case for Wages for Housework. Toronto: Wages Due Lesbians. Cover woodcut by Anne Quigley. CLGA collection, in monographs, folder M 1985-054].](https://www.heritage-matters.ca/uploads/Articles/Wages-Due-Lesbians_Wyland-pamphlet-image-web.jpg)