Browse by category

- Adaptive reuse

- Archaeology

- Arts and creativity

- Black heritage

- Buildings and architecture

- Communication

- Community

- Cultural landscapes

- Cultural objects

- Design

- Economics of heritage

- Environment

- Expanding the narrative

- Food

- Francophone heritage

- Indigenous heritage

- Intangible heritage

- Medical heritage

- Military heritage

- MyOntario

- Natural heritage

- Sport heritage

- Tools for conservation

- Women's heritage

Pimachiowin Aki – Canada’s newest World Heritage Site

On July 1, 2018, during the 42nd Session of the World Heritage Committee in Manama, Bahrain, Pimachiowin Aki was inscribed on the UNESCO World Heritage List – Canada’s first “mixed” (cultural and natural) World Heritage Site. In response to the committee’s decision, Anishinaabe First Nation spokesperson Sophia Rabliauskas acknowledged the guidance of our Elders and recounted how the Anishinaabeg (Ojibwe people) have lived and cared for this land for thousands of years – a sacred responsibility given to us by the Creator that ensures life for our children and grandchildren.

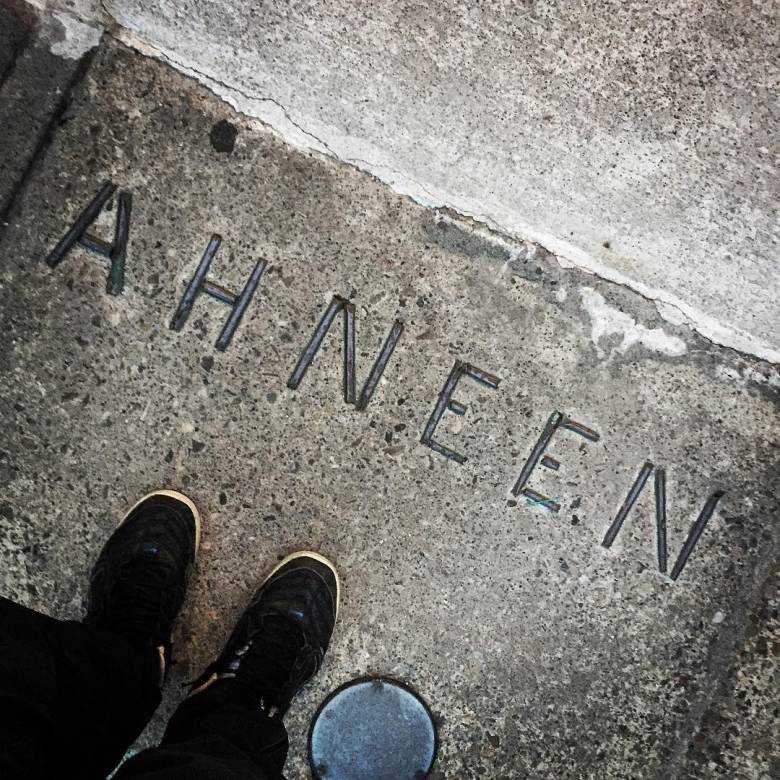

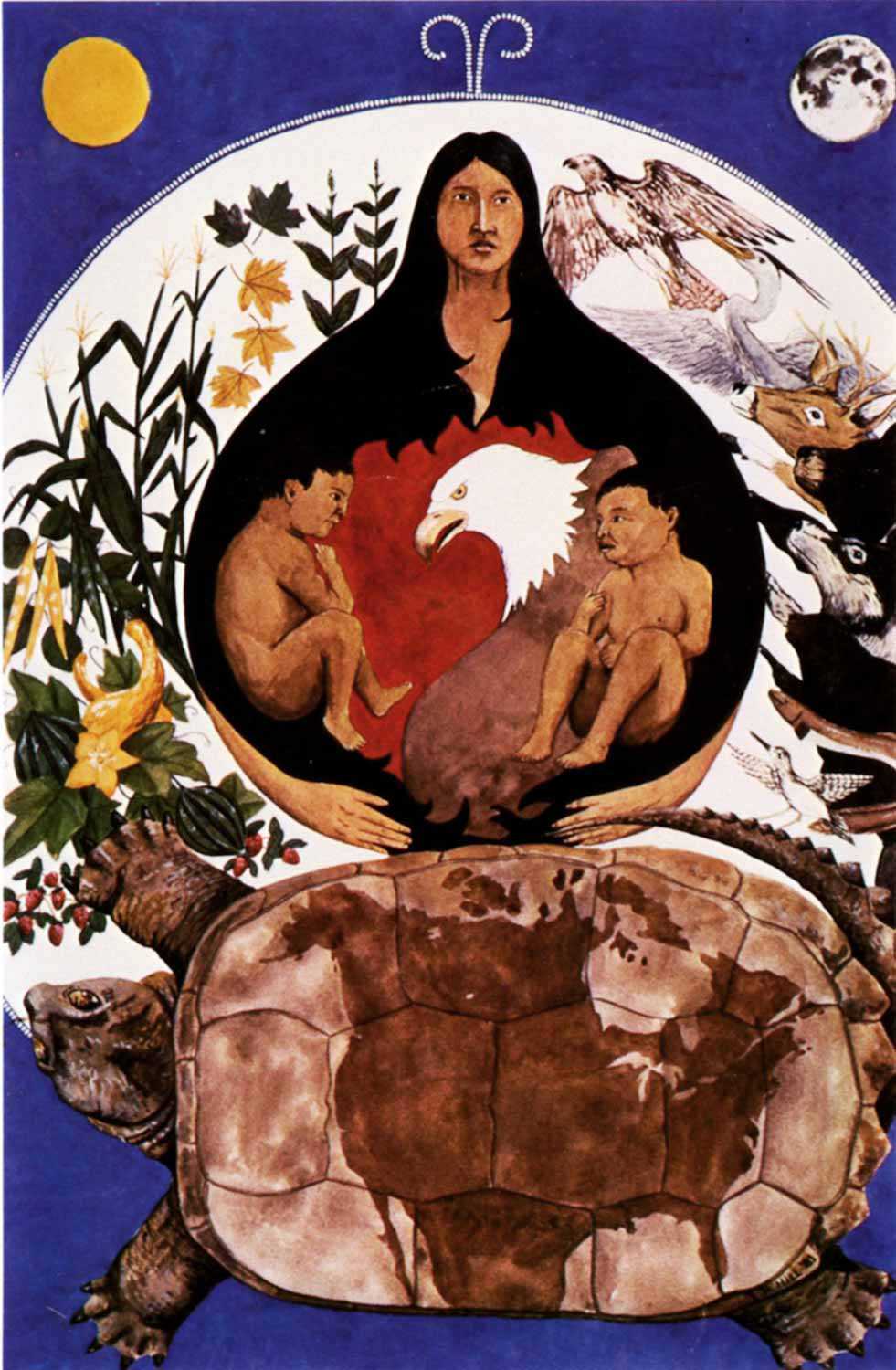

Pimachiowin (pronounced pim-MA-cho-win) means “the good life.” This is the greatest ambition of Anishinaabeg. The good life includes hunting success, economic stability, good health into old age, and healthy, happy children. Aki (pronounced ah-KAY) means “land.” Aki is a holistic concept of land in which no distinction is made between “the spirit beings” and “those who have life.” Pimachiowin Aki together means “the land that gives life.” Pimachiowin Aki is a manifestation of an enduring kinship between culture and nature.

Fish have always been an important resource for Anishinaabeg. (Photo: Pimachiowin Aki Corporation | Credit: Hidehiro Otake)

“We all fit side by side on this circle [of life], and we all are important, depending on each other for life. No one is more important than the other. That is why we have a strong relationship with all life.” Albert Bittern (November, 2013)

Covering 29,040 square kilometers of central Canada’s boreal shield, and spanning the Manitoba-Ontario border, Pimachiowin Aki is among the 20th largest World Heritage Sites, and is rare in the world – less than one per cent of all World Heritage Sites are in the mixed site-cultural landscape category.

Pimachiowin Aki is comprised of ancestral lands of the Bloodvein River, Little Grand Rapids, Pauingassi and Poplar River Anishinaabe First Nations, with a total population of 6,000 people. Atikaki Provincial Park (Manitoba) as well as Woodland Caribou Provincial Park and Eagle-Snowshoe Conservation Reserve (Ontario) complete the site.

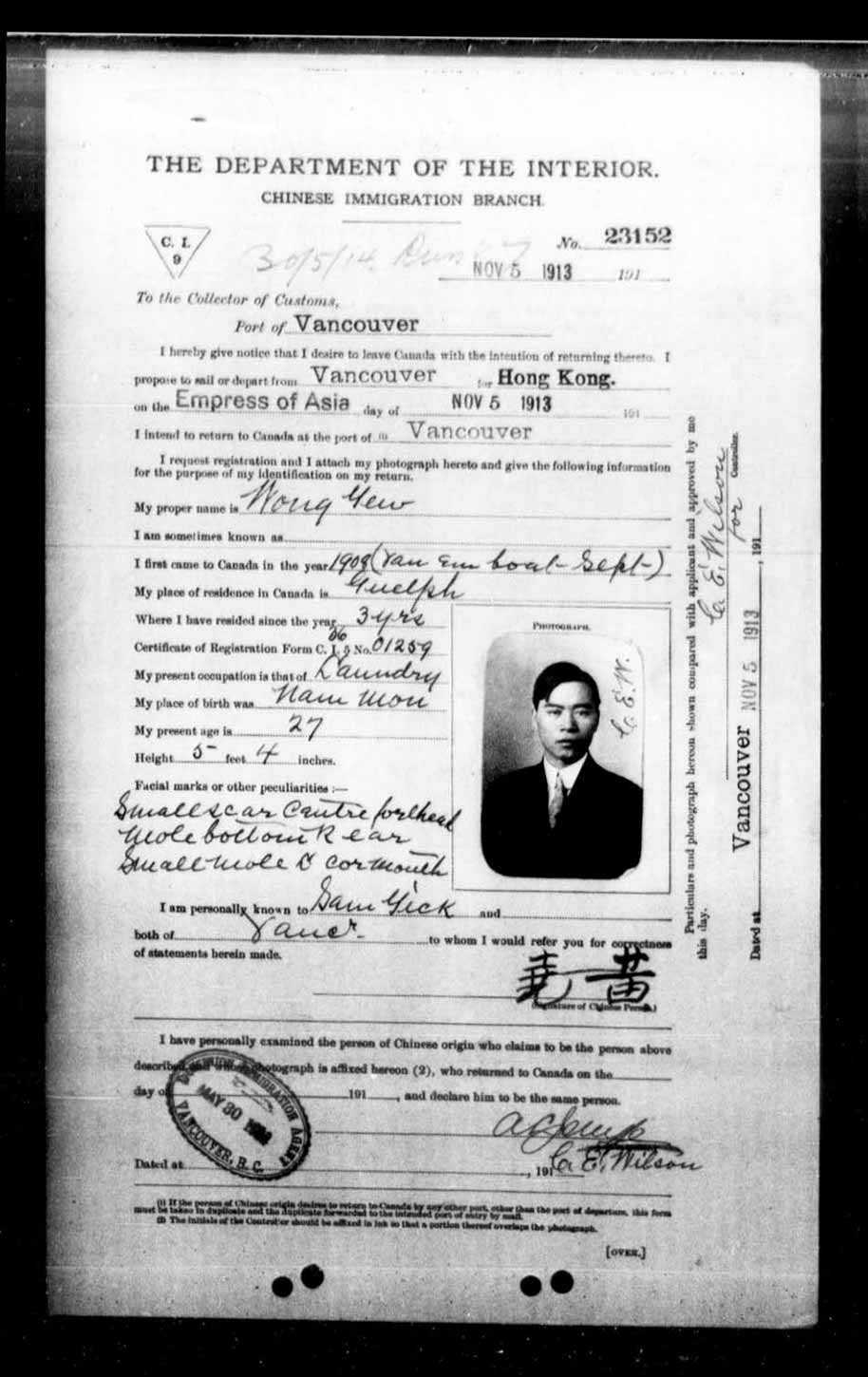

In 2002, the Pimachiowin Aki First Nations signed the Protected Areas and First Nations Resource Stewardship: A Cooperative Relationship Accord (the Accord). Through the Accord, the First Nations set out the vision of a network of protected areas worthy of inscription on the World Heritage List. The governments of Ontario and Manitoba joined with the First Nations to propose Pimachiowin Aki’s inclusion on Canada’s Tentative List of World Heritage Sites in May 2004. In 2006, the First Nation and provincial government partners established the Pimachiowin Aki Corporation to oversee preparation of the nomination dossier. The Corporation is a non-profit, charitable organization governed by a Board of Directors that represents the First Nations and provincial governments.

The first nomination was deferred by the World Heritage Committee in 2013. The Committee recommended an upstream advisory mission to explore ways to strengthen the nomination to fit better with the selection criteria of World Heritage Sites and the cultural landscape concept. At the time, the Committee acknowledged that although the World Heritage Convention is the sole international convention that relates to both cultural and natural heritage, it does not adequately recognize the indissoluble bonds that exist in some places between culture and nature. A second nomination in 2015 elaborated on the testimony of Pimachiowin Aki to the cultural tradition of Ji-ganawendamang Gidakiiminaan, or “keeping the land,” and was recommended by the advisory bodies to the World Heritage Committee – the International Council on Monuments and Sites and the International Union for the Conservation of Nature – for inscription during the July 2016 World Heritage Committee session. The advisory bodies lauded this nomination as a watershed in representing the seamless links between culture and nature and customary stewardship knowledge, beliefs and practices, and as a landmark for sites nominated through the commitment of Indigenous peoples.

In June 2016, one of the original five First Nations withdrew support for the nomination, and as a result, the nomination was referred back to Canada for revision.

The third nomination, approved in July 2018, fully met the intent of the World Heritage Convention: to protect, preserve and present places of outstanding universal value.

We strongly believe that nature and culture are inseparable. This nomination describes our cultural tradition of ji-ganawendamang Gidakiminaan, keeping the land, which reflects our sacred responsibility and spiritual connection to the boreal forest of Pimachiowin Aki (the land that gives life). It also describes the responsibility that each generation has carried to ensure life will continue for generations to come.

As Anishinaabe people we want to leave a lasting legacy to protect and preserve of this area for the benefit of the planet. (Sophia Rabliauskas, July 1, 2018, excerpt from remarks to the World Heritage committee following the inscription of Pimachiowin Aki on the World Heritage list)

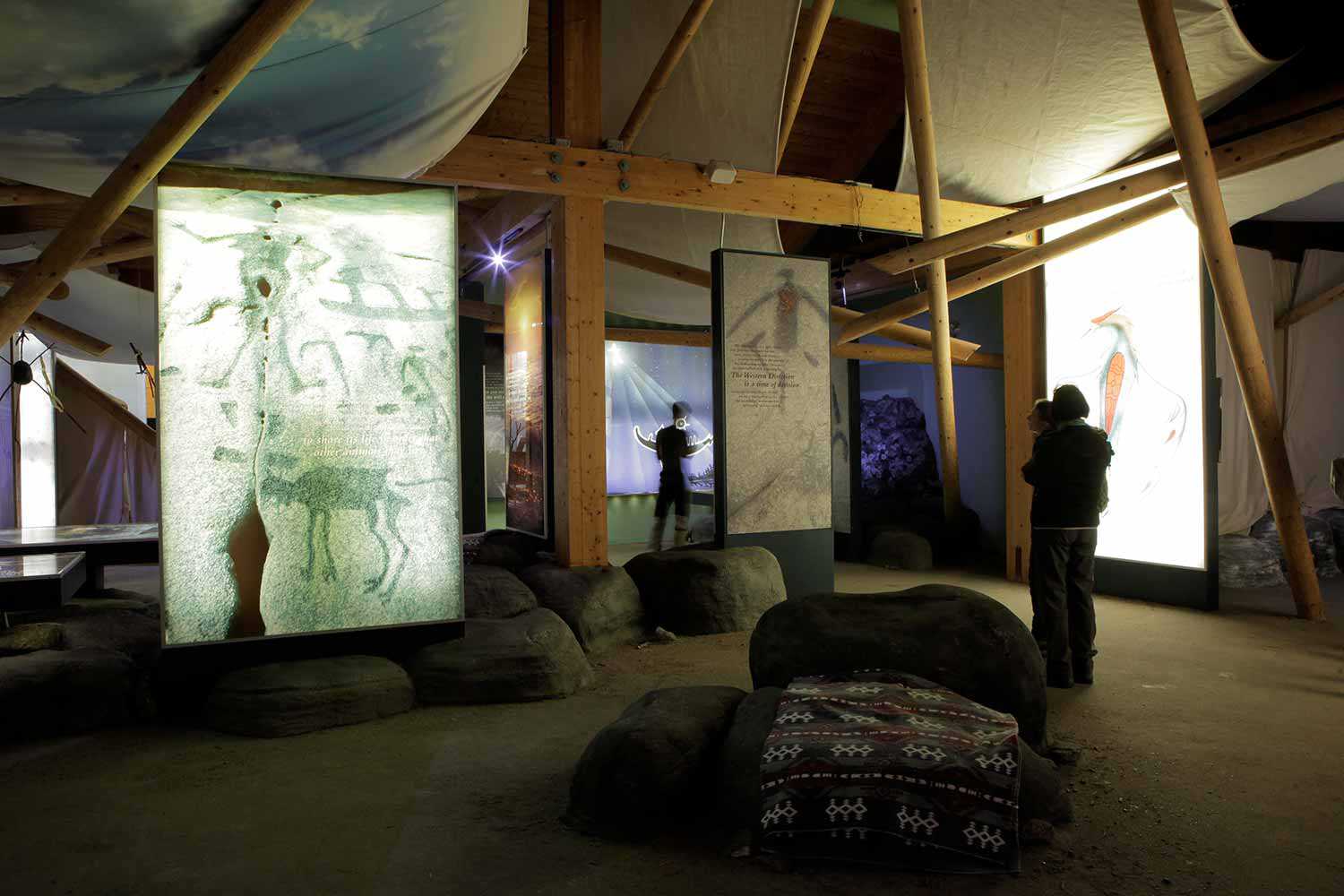

Pimachiowin Aki is the most complete and therefore exceptional example of a landscape within the North American subarctic geocultural area that provides testimony to the cultural tradition of Ji-ganawendamang Gidakiiminaan. The cultural tradition is reflected through tangible and spatial expressions of Anishinaabe interactions with the land, such as pictographs (rock art) and other archaeological, sacred and ceremonial sites, travel routes, cabin and camp sites, harvesting and processing sites, traplines and named places. Anishinaabeg are also connected to the land through intangible attributes, including Anishinaabemowin (the Anishinaabe language), knowledge, social relations, beliefs and cultural values associated with Ji-ganawendamang Gidakiiminaan.

“Teachings are shared through drumming, singing, community gatherings, offerings. For as long as we remember, the elder that has the most knowledge and wisdom is the community leader. This elder would perform traditional drum songs and provide traditional medicine for healing.” Solomon Pascal (from translation, January 2014)

Pimachiowin Aki is an exceptional example of the global boreal biome, and is the best example of the ecological and biological diversity of the North American boreal shield ecozone. Pimachiowin Aki contains an exceptional diversity of terrestrial and freshwater ecosystems and fully supports wildfire, nutrient flow and species movements and predator-prey relationships, which are essential ecological processes in the boreal forest. Large protected areas like Pimachiowin Aki are necessary to maintain ecological processes and ecological integrity, and to maintain networks of sites supporting Indigenous livelihoods and cultural traditions.

Moving forward, the Pimachiowin Aki Corporation will play an integral role in safeguarding the outstanding universal value of this special place and realizing social, cultural, environmental and economic benefits within and beyond the new World Heritage Site. Key programs areas include:

- Safeguarding tangible and intangible cultural heritage

- Conserving and understanding ecosystems and species

- Supporting sustainable economies

- Informing and educating the public

- Coordinating monitoring and reporting

- Supporting community-based initiatives

An early priority is the establishment of a Pimachiowin Aki Indigenous Land Guardians program.

The Pimachiowin Aki partners are grateful to everyone who has supported this initiative, from Anishinaabe Elders, leaders and community members to the provinces of Ontario and Manitoba, the government of Canada and to the many individuals and organizations who have contributed their time, energy and talents to protect and transmit to future generations this exceptional and irreplaceable heritage. For more information, visit pimachiowinaki.org.