Browse by category

- Adaptive reuse

- Archaeology

- Arts and creativity

- Black heritage

- Buildings and architecture

- Communication

- Community

- Cultural landscapes

- Cultural objects

- Design

- Economics of heritage

- Environment

- Expanding the narrative

- Food

- Francophone heritage

- Indigenous heritage

- Intangible heritage

- Medical heritage

- Military heritage

- MyOntario

- Natural heritage

- Sport heritage

- Tools for conservation

- Women's heritage

Perspectives on a site: Artifacts, fragments and layers

Archaeology, Buildings and architecture

Published Date: Dec 05, 2014

Photo: 2007 excavations uncovered Macdonell’s icehouse and smokehouse

When the Trust conserves a property as complex as Macdonell-Williamson House, we consider a variety of perspectives related to the site as an artifact – both below and above ground. Exploring the underground landscape can help explain the greater context of the site, revealing its historical climate, economy, politics and culture. Unique archival evidence is also embodied in the architecture itself, which allows us to understand the evolution and use of the building’s fabric over time. Exploring each nook and cranny shows a layered past that helps to illustrate an important era in Canada’s development.

The following perspectives converge to create a unique lens through which we can come to a better understanding of the site and its place in our history.

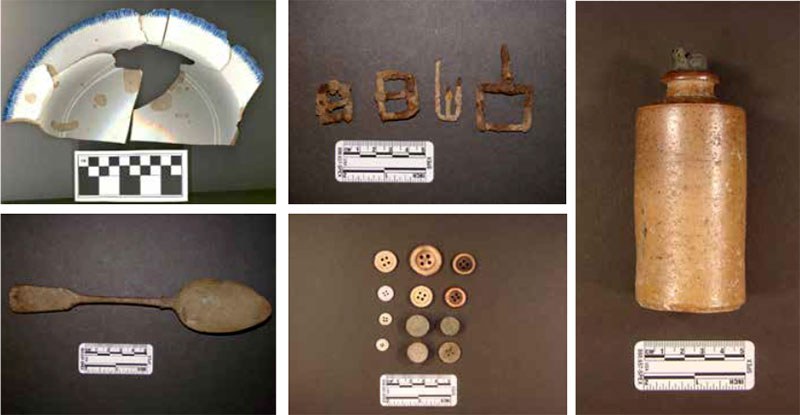

Over 135,000 artifacts were excavated during multiple field seasons at the MacDonell-Williamson site. Clockwise from top left: a blue edged platter, horse harness buckles, a stoneware bottle with cork intact, various buttons and a spoon.

Archaeology by Dena Doroszenko

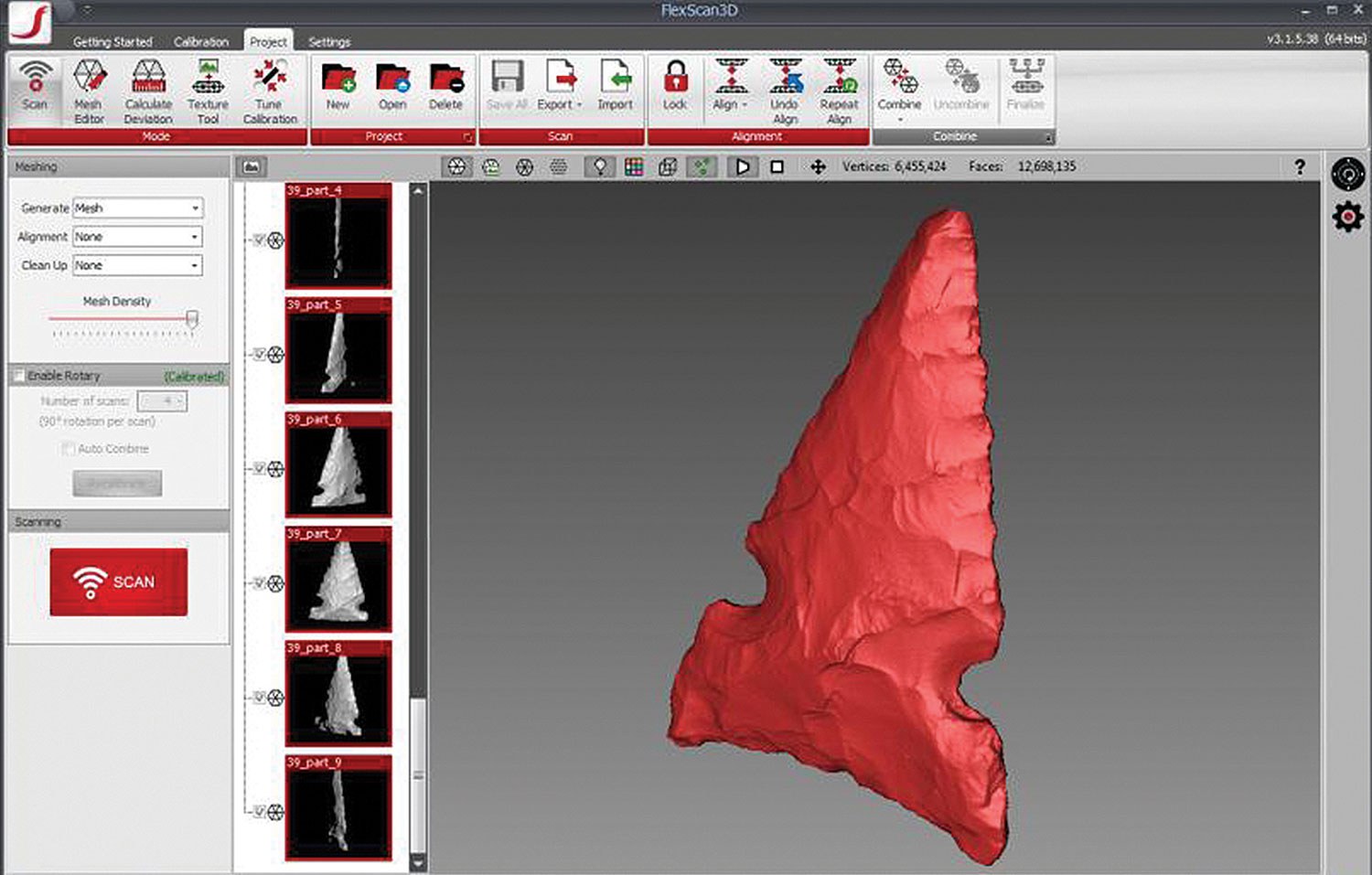

Archaeology reveals the story of the distant and recent past through the discovery, examination and interpretation of fragments. By their very nature, artifacts are evocative objects from the past, and they can also be studied and made legible.

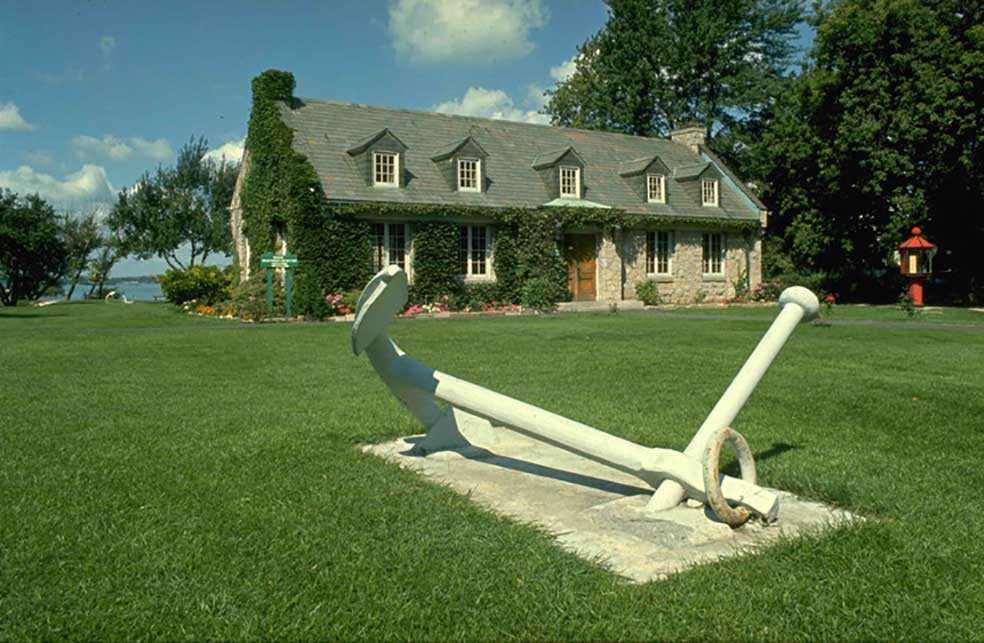

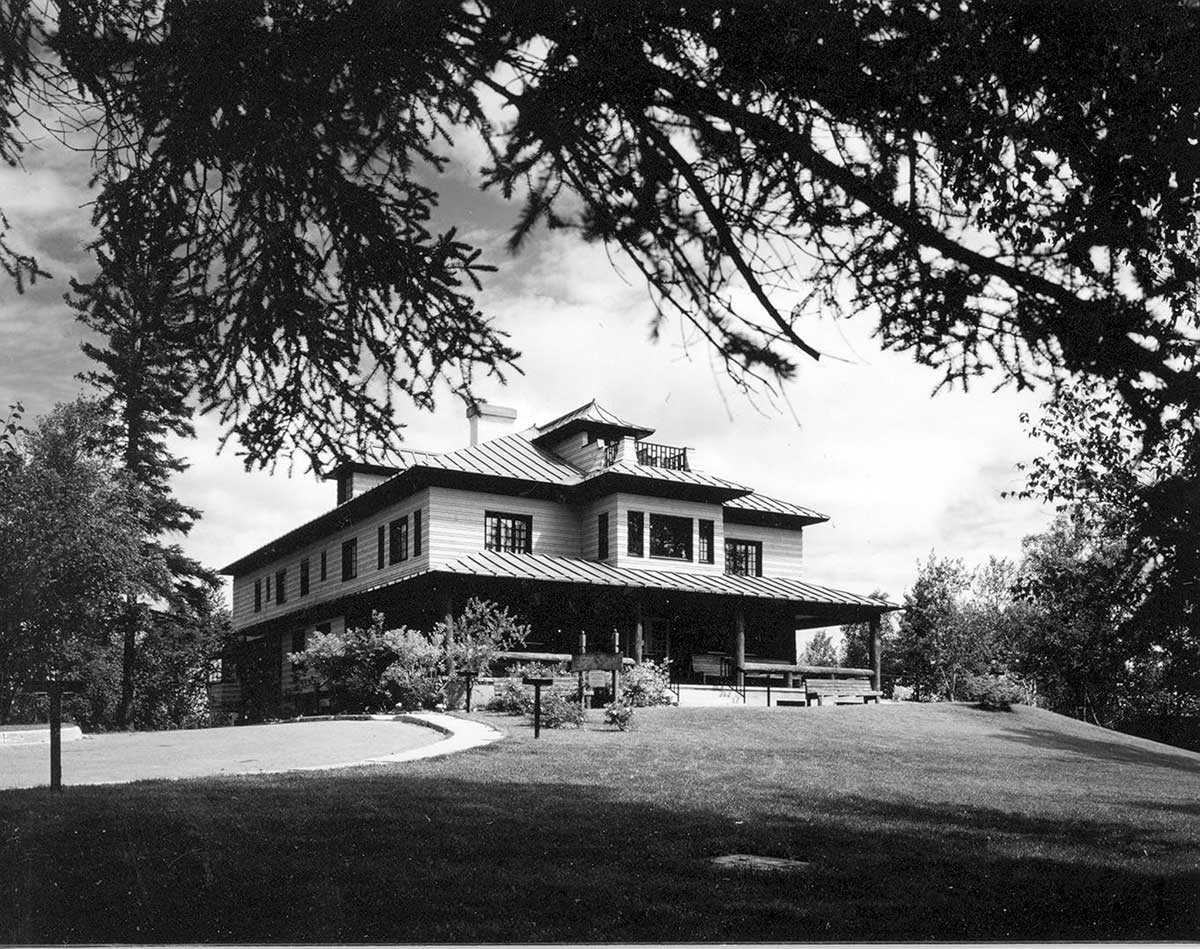

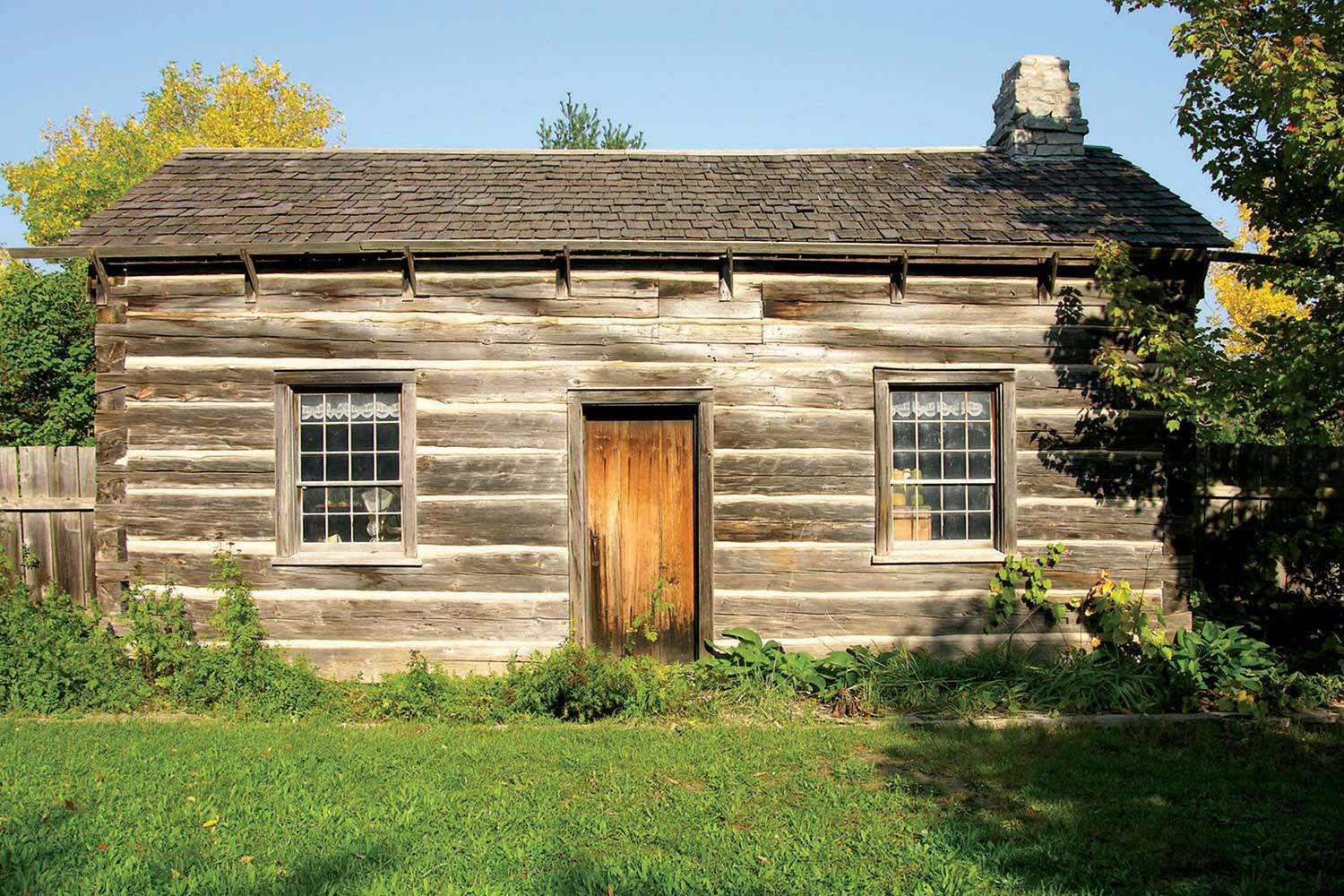

The Trust-owned Macdonell-Williamson site – on a bluff above the Ottawa River in eastern Ontario – is a landscape of artifacts: the landmark 18th-century stone house being perhaps the most complex artifact of all. At this site, archaeology of the below-ground and above-ground variety is being used to enhance the historical narrative, and to develop an interpretive experience that embraces the concepts and values of patina, artifact and ruin.

The distant past

“Spanish John” Macdonell settled in New York state and then in St. Andrews West in the early 1790s. In 1793, his 25-year-old son John signed on as a clerk for the North West Company and soon became a partner. John Macdonell established a large family with his wife, Magdeleine Poitras. On his retirement, he moved the family to Montreal and, by 1813, bought a large property on the Ottawa River adjacent to the village of Pointe Fortune and the Carillon rapids.

The land that Macdonell purchased was first patented in 1788 by William Fortune and contained numerous buildings. The large house that Macdonell built in 1817 implies that the family lived in relative affluence. Historical documentation and the archaeological record, however, suggest that Macdonell never attained this level of prosperity.

As early as 1820, just three years after building his house, he was in financial difficulty. The years that followed were less than kind to him for he was plagued by constant financial problems and personal tragedies. Nevertheless, the freight forwarding business he had established at first appeared successful. In 1821, the fur trade company for which Macdonell had once worked ceased to exist after amalgamation with its rival, the Hudson’s Bay Company. This development had a significant impact on his life. It meant that he earned less from his fur trade interest than he had expected. This reversal of fortune at the time he was building his spacious home was probably quickly felt. Even worse, Macdonell’s chosen location for his home was suddenly rendered irrelevant when the Hudson’s Bay Company opted not to use the Ottawa waterway to bring goods to the interior.

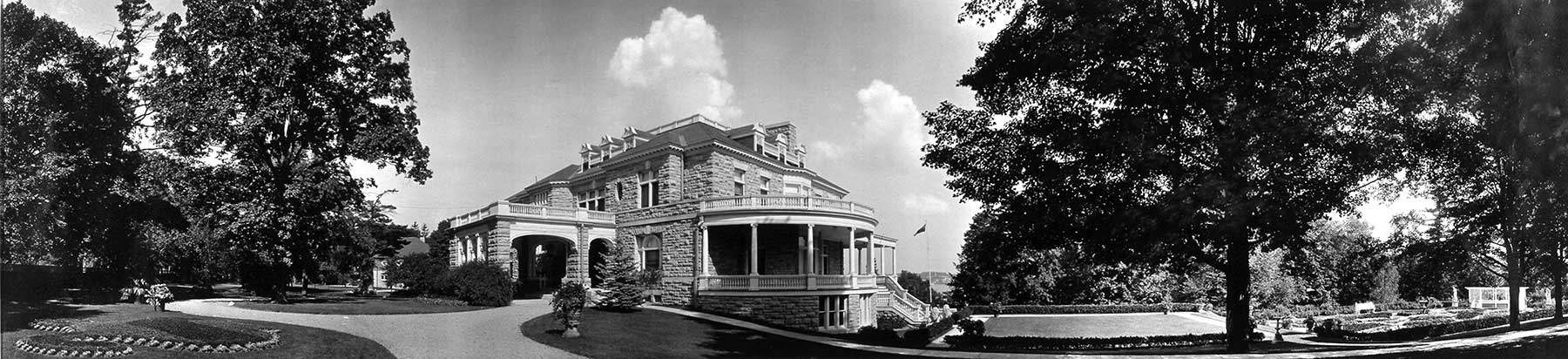

On April 17, 1850, John Macdonell died at his home. He was 81. He left the house to his son, John Beverly Palafox Macdonell. By 1882, when the property was sold to the Williamson family, only three acres (1 hectare) remained of the original 1,400 acres (566 hectares). The Williamson family and their descendants occupied the house for the next 79 years and made significant changes to the house and outbuildings, but preserved the three acres that the Ontario Heritage Trust holds in trust today.

The recent past

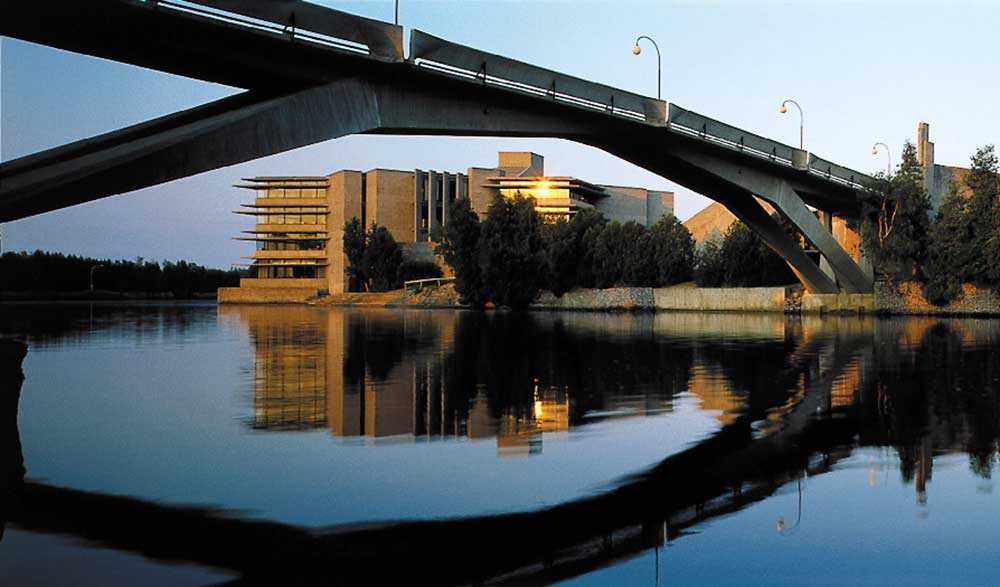

It seemed that the fate of the house was sealed when it was expropriated by Quebec Hydro in 1961 for the Carillon hydroelectric development. The dam was eventually constructed farther upstream and the house was spared, but left abandoned. It was designated a National Historic Site by the Government of Canada in 1969 and was acquired by the Ontario Heritage Trust in 1978. In 1995, the Friends of the Macdonell-Williamson House formed to become the Trust’s operating partner and to run the property as a seasonal heritage attraction. This partnership initiated a period of investment in the study, archaeology and architectural preservation of the site that continues today.

The archaeological landscape

The Macdonell-Williamson property has evolved tremendously over more than 220 years. The archaeological landscape is a cultural construct in which our sense of place is transformed and changed by an understanding of history partly revealed through archaeology. What we see today, however, is not the site as it once was – a village-based culture with a thriving farm and business complex. A desire to read this landscape of ruins suggested by the historical record led to a series of archaeological investigations, beginning in 1978.

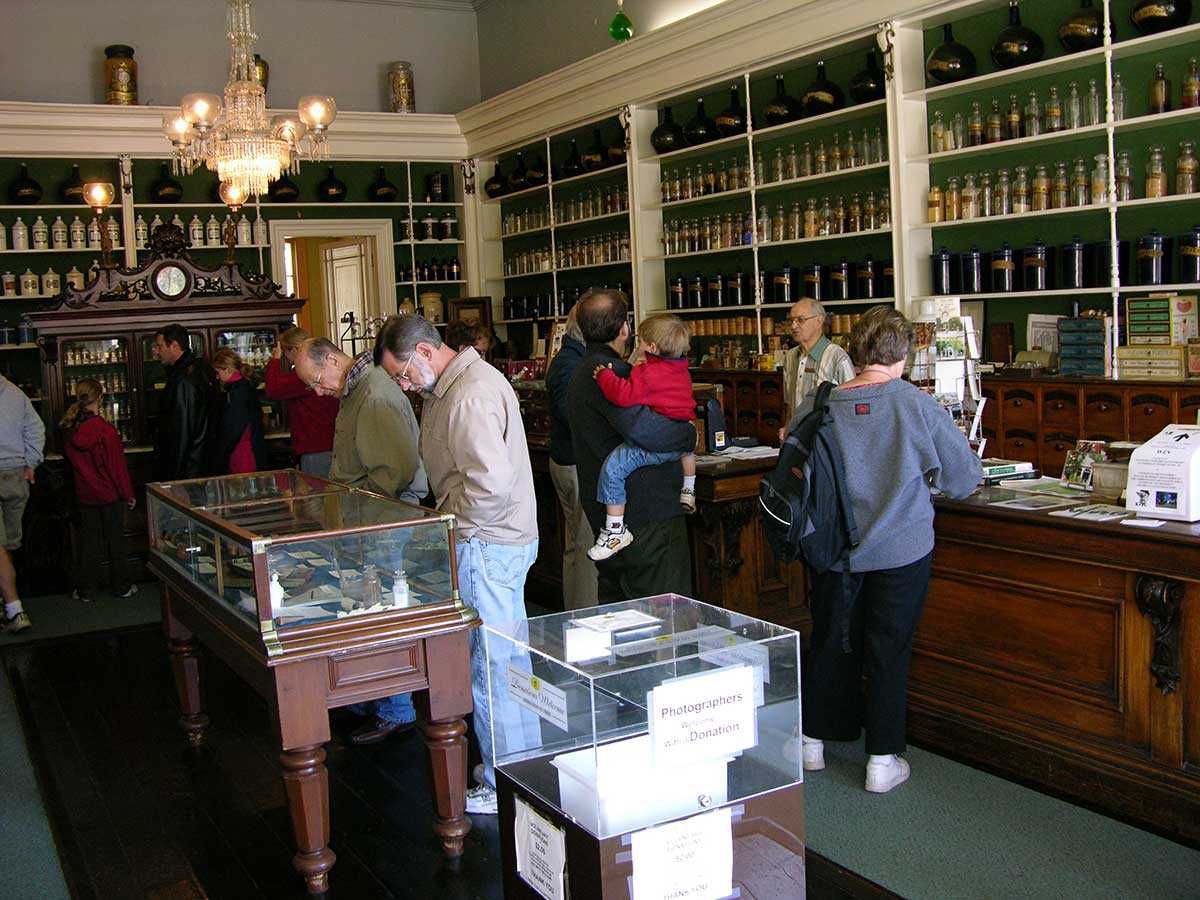

We know that John Macdonell was prolific in constructing outbuildings during his occupation of the property. Between 1817 and 1842, he built over 20 outbuildings; in the space of just one acre, six have been discovered archaeologically since 1981.

The work of several excavations has uncovered a wealth of physical records and new information, including structural evidence of earlier buildings. The foundations of the retail store built by Macdonell in 1822 were excavated to the north of the house. Excavation east of the basement entrance uncovered a massive stone foundation that runs diagonally to the main house wall. Based on the recovery of 18th-century coins associated with this feature, this structure may be one of the buildings that William Fortune constructed (and that appears on a 1797 map). Excavations of the southeast lawn area uncovered a late-19th-century driveway bedding surface and a dry-laid wall. This wall may be related to one of the Macdonell buildings appearing on the 1829 historical map of the property.

The 2003 field season uncovered the stone foundations of an earlier building pre-dating the foundations at the north end of the shed on the north side of the house. These stone foundations likely represent the 1820s icehouse and smokehouse that are also shown on the 1829 map. Close to the house, five intact stone window wells and one dismantled window well along the west and south façades of the house were discovered; the blocked-up windows remain visible in the basement walls of the house.

All of these building foundations, so meticulously excavated, were documented and then carefully backfilled to ensure their preservation. They are again hidden from visitors. Yet, for interpretive purposes, they are part of the archaeological landscape.

Archaeology has recovered over 135,000 artifacts at the Macdonell-Williamson property and has contributed to an understanding of the farmstead landscape as it developed over time. The placement of foundations on the site seems to indicate a clustering around the house. On the east lawn, a collection of outbuildings are placed around the house, perhaps forming an entrance to the house through a courtyard.

These outbuildings include the 1822 retail shop, the icehouse and smokehouse as well as possibly a drive shed or stable. These are all functions related to the house, as well as the personal and business needs of its occupants, not necessarily the concerns of the farm and estate as a whole. The current road running to the immediate south of the house may originally have been a laneway and the outbuildings associated with agriculture and livestock placed on the other side, away from the house. As farms and farmers grew in personal wealth, the layout tended to change toward the courtyard or dispersed plan, with clear divisions between farm and farmhouse. Macdonell appears to have followed this pattern, creating a separation between farm functions – that is, between his home and his business interests.

Archaeological fragments

Artifacts allow archaeologists to reconstruct the past and to theorize about how the movement of these objects or fragments was affected by social, economic and technological change in a household over time.

At times, archaeology serves to document the past before its traces are completely lost or removed. Such was the case when half of the basement of the house was excavated prior to the installation of a new floor slab. General conclusions can be made regarding the nature of the deposition of the large quantity of artifacts discovered.

There were large amounts of animal bones as evidence of the problem of rodent infestation on the property over the years. The large quantity of nails that were discovered indicates the replacement of the wood floors, at least twice in the history of the house, and then the gradual disintegration of existing floorboards due to rising damp. The presence of the original floor joist system was recorded through the east half of the basement. Original stone fireplace hearths in the northeast and southeast rooms were also recorded. One artifact of note that was discovered is a Copeland Garret/late Spode tea bowl (blue transfer print, c. 1833- 47). Fragments of this bowl were recovered during the 1981 excavations and additional fragments were found during the 2009 field season that mend directly onto this vessel, allowing reconstruction of its original profile.

The architectural artifact by Romas Bubelis

Unearthed historical archaeological artifacts are static objects without current functional use as originally intended. But an architectural artifact like the Macdonell-Williamson House is an object that continues to be used and is therefore subject to continuing change.

This change may be expressed as a desire to go back through restoration or even reconstruction or it may move forward through rehabilitation and re-use. But, if surviving, original, aged material and finishes are recognized as having a certain authority, then a preservation approach to fragments, patina and layers must also be embraced.

In 2014, a project to reinforce the timberframe structure of the Macdonell-Williamson House required that it be completely emptied of its contents. This clearing of movable objects brought the character of the house as artifact into sharp focus and raised issues around the value of emptiness, the power of ruin as an interpretive strategy and building archaeology as a method of understanding the layers of surviving building fabric.

Precedents

Nowhere is emptiness more agreeable than in the case of architectural ruins where the appreciation of the effects of the passage of time is accompanied by a certain sense of abandonment and melancholy where human activity is imagined in the past tense.

The appropriation of emptiness, partial ruin and building archaeology in heritage museums is not without precedent. Drayton Hall, located near Charleston, South Carolina, is one of the oldest preserved plantation houses in the United States. Built in 1738, it amazingly retains most of its interior plaster and fine Georgian woodwork and finishes. Following seven generations of family ownership, the Draytons donated the property to the National Trust for Historic Preservation in 1974. In an unusual move, the National Trust decided to preserve the house as it was received. It remains to this day without modern environmental controls and is treated as a laboratory to explore techniques for conservation of its 18th-century fabric. Although a heritage attraction, it was intentionally left empty of furnishings and cultural objects in order to focus on the building itself as an artifact worth studying. As a consequence, perhaps intended and perhaps not, the melancholy grandeur of the place is intensified by its emptiness.

A more recent precedent can be found in the Tenement Museum in New York City’s Lower East Side. Founded in 1988, this museum seeks to interpret the 19th- and 20th-century immigrant experience as lived in a typical tenement apartment block. The subject block was built in 1863 and was home to hundreds of families, and received multiple alterations throughout its 72 years of operation. It was boarded up and abandoned in 1935, surviving as a virtual time capsule for the next 50 years.

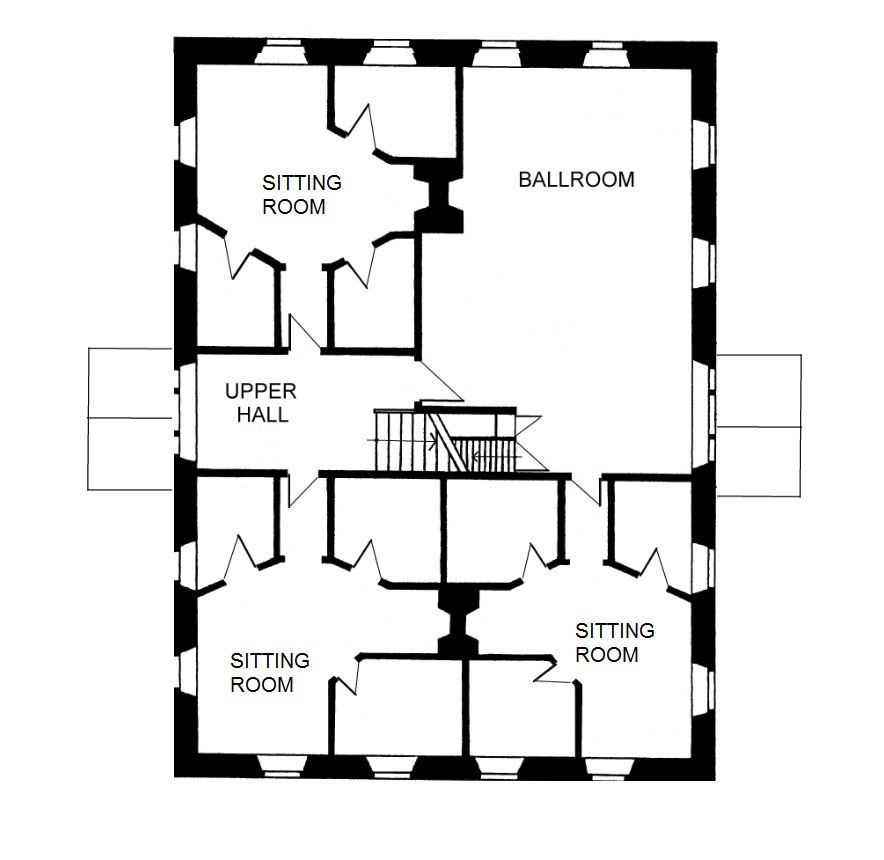

Half of its apartments were restored, furnished and interpreted to represent the lives of previous tenants from specific periods, but the remaining apartments were left in as-found condition – unfurnished, with old fittings, peeling faded paint and chipped railings, worn stairs and door casings – bearing the traces of former inhabitants. The restored domain is entered through the as-found one. To stand in these stifling rooms and corridors is to reflect on tenement life and trigger an imagination of what it might have been like. In their preservation philosophy, architects Li-Saltzman wrote that the tenement project “is predicated on retaining the palpable sense of history contained within its walls, and on providing both the experience of the tenement as people lived there, and as it was found.” The Macdonell-Williamson House in Pointe Fortune falls somewhere between the exceptional grandeur of Drayton Hall and the humility of the New York Tenement Museum. When built in 1817, Macdonell-Williamson House was a notably grand undertaking in both size and craftsmanship, considering Pointe-Fortune’s then-wilderness location on the Ottawa River some 60 miles (100 kilometres) upstream from Montreal. The principal rooms received decorative plaster cornices and panelled wood window surrounds of exceptional quality. A generously proportioned ballroom with elaborate ceiling medallion was included on the second floor. Clusters of bed-closets opening onto a common sitting room with a fireplace was an ingenious arrangement of sleeping quarters for Macdonell’s large family of 12 children in what would have been a difficult house to heat. In its day, it would have been an exceptionally fine house.

The power of ruin

What we see today, of course, is different but no less intriguing – a visual character that has become complex and diffuse because it evolved as a result of historical circumstances. It comprises fragments from different eras that, taken together, are more evocative of the building’s life than a restoration or reconstruction approximating the original could be. An archaeological sensibility that includes research, observation and analysis is needed to look beyond the deterioration and to appreciate the building fabric.

The strained finances of John Macdonell – and then of his son – meant that the interiors, although grand, where not redecorated with the customary frequency. The Williamsons, however, inadvertently protected many early finishes by covering them with wallpaper. For most of the 80 years following the Macdonell era, the house was used only seasonally. It was never wired for electricity and had no plumbing or heating system other than the original fireplaces. The absence of such modernizations in no small measure accounts for its current feeling of antiquity. Lastly, the house was vacant from its expropriation in 1961 until about 1995. During this lengthy period, much detail was lost to vandalism and theft, or through accelerated deterioration from water damage.

Much of the site’s remaining national heritage significance resides in the quality and quantity of the building’s surviving early-19th-century decorative plasterwork and painted finishes, particularly those on the second floor remaining in aged and unrestored condition. The ballroom’s beaded concave plaster cornice adorned with grape leaves and a row of projecting acanthus leaves is missing in sections, but there is more than enough left to evoke a sense of its former splendour.

The breaks reveal it in cross-section. The surviving plaster is in frail condition – the lime in its core having leeched out, leaving only sand with a thin gypsum outer crust. Much of this decorative plaster is painted over with calcimine. The staircase has a curved ceiling with deep blue calcimine paint of an intense hue and flat finish characteristic of the building’s earliest period.

Calcimine is a water-soluble paint that was favoured for plaster mouldings because it could be easily washed off prior to recoating in order to avoid loss of sharpness due to paint build-up. Its survival into the 21st century is unexpected and rare. Elsewhere, walls have been over-coated with successive colours, now faded or partially chipped away, creating a rich colour matrix of depth and texture. In the basement, only remnants of the original lath and plaster ceiling remain, tucked between hewn timber beams accentuated with decorative beaded edges. In contrast, the plaster cornice of the ground-floor dining room is completely intact, requiring only minor repair to maintain its original integrity.

Interpretation

The house today is an amalgam of recent preservation efforts that include part rehabilitation, part restoration and those elements preserved in partial ruin. The latter are treasured – unlike the former, they cannot be re-created. Like fragmented archaeological artifacts, these architectural artifacts speak loudest when left unaltered and in isolation.

Perhaps restoration architect Peter John Stokes got it right in a report to the Historic Sites and Monuments Board of Canada in 1969. He wrote: “Perhaps museum use on a limited basis suggested, of work in progress, of the isolated piece of fine furniture in what is basically an excellent architectural exhibit per se, and the graphic illustration techniques used as an interpretive supplement are all that this scheme should include.”