Browse by category

- Adaptive reuse

- Archaeology

- Arts and creativity

- Black heritage

- Buildings and architecture

- Communication

- Community

- Cultural landscapes

- Cultural objects

- Design

- Economics of heritage

- Environment

- Expanding the narrative

- Food

- Francophone heritage

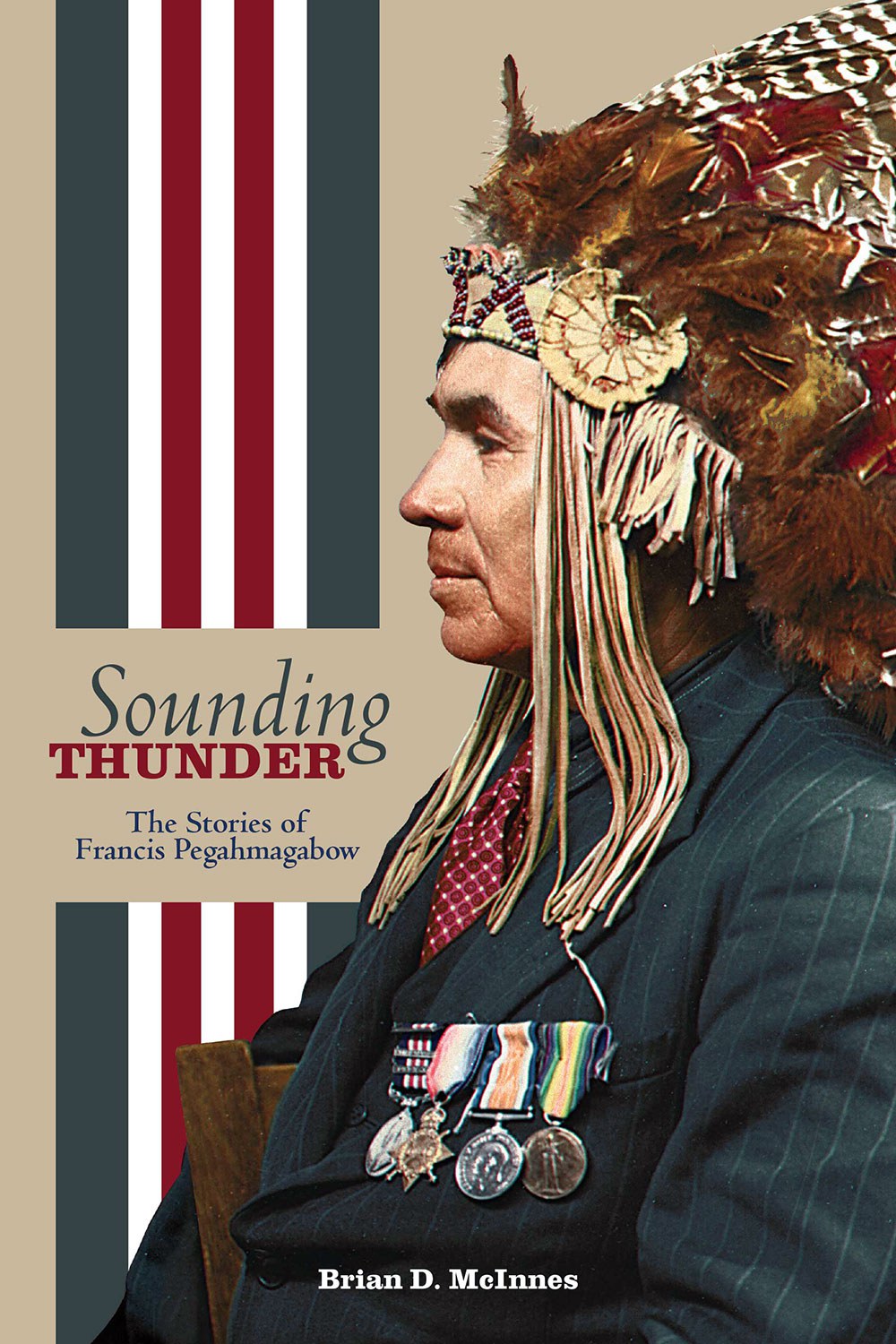

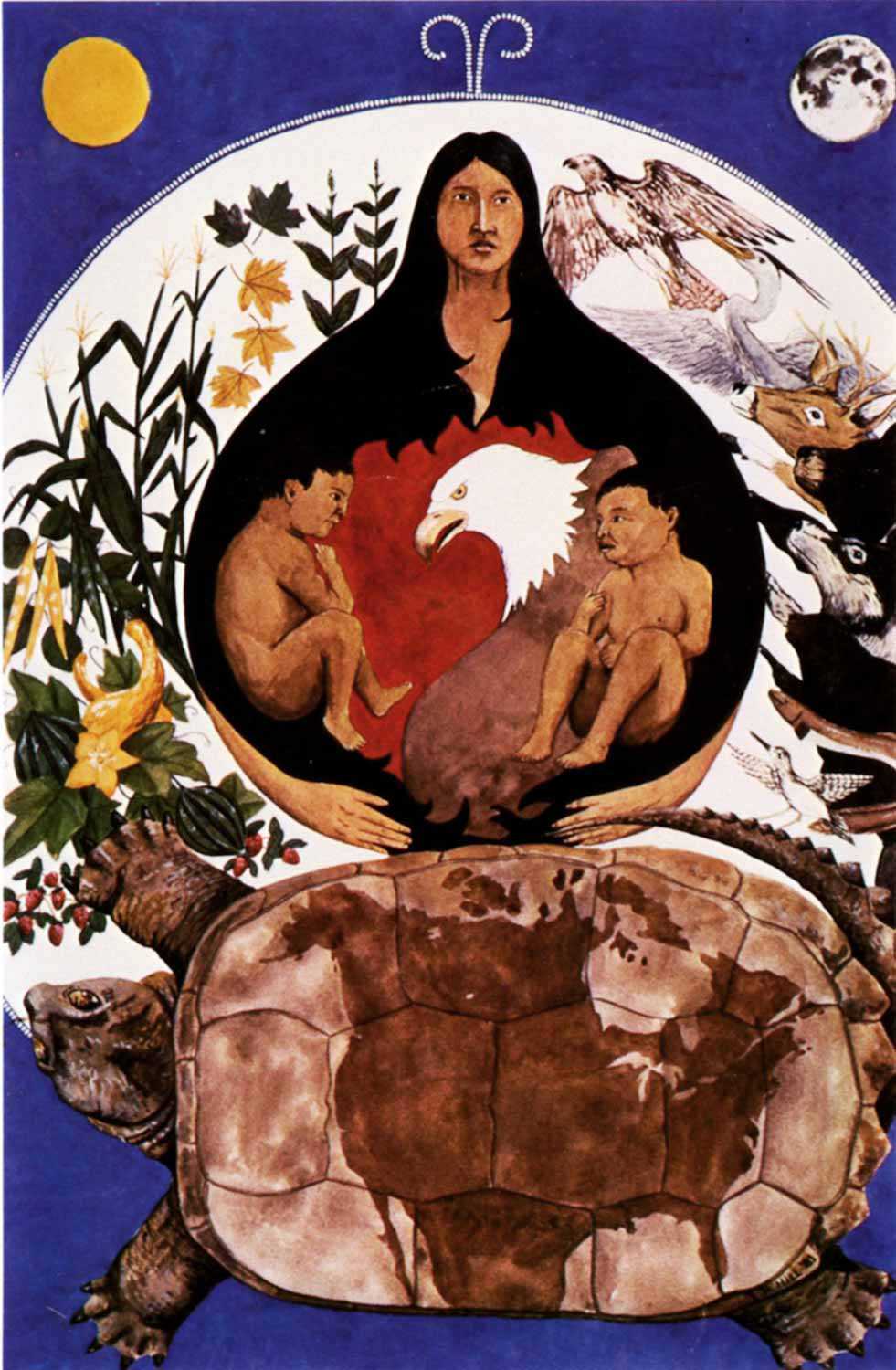

- Indigenous heritage

- Intangible heritage

- Medical heritage

- Military heritage

- MyOntario

- Natural heritage

- Sport heritage

- Tools for conservation

- Women's heritage

Ontario’s rich religious heritage

"“Although the churches established during the early period of British rule were of different denominations, their congregants shared common linguistic, cultural and political experiences that brought them together"."

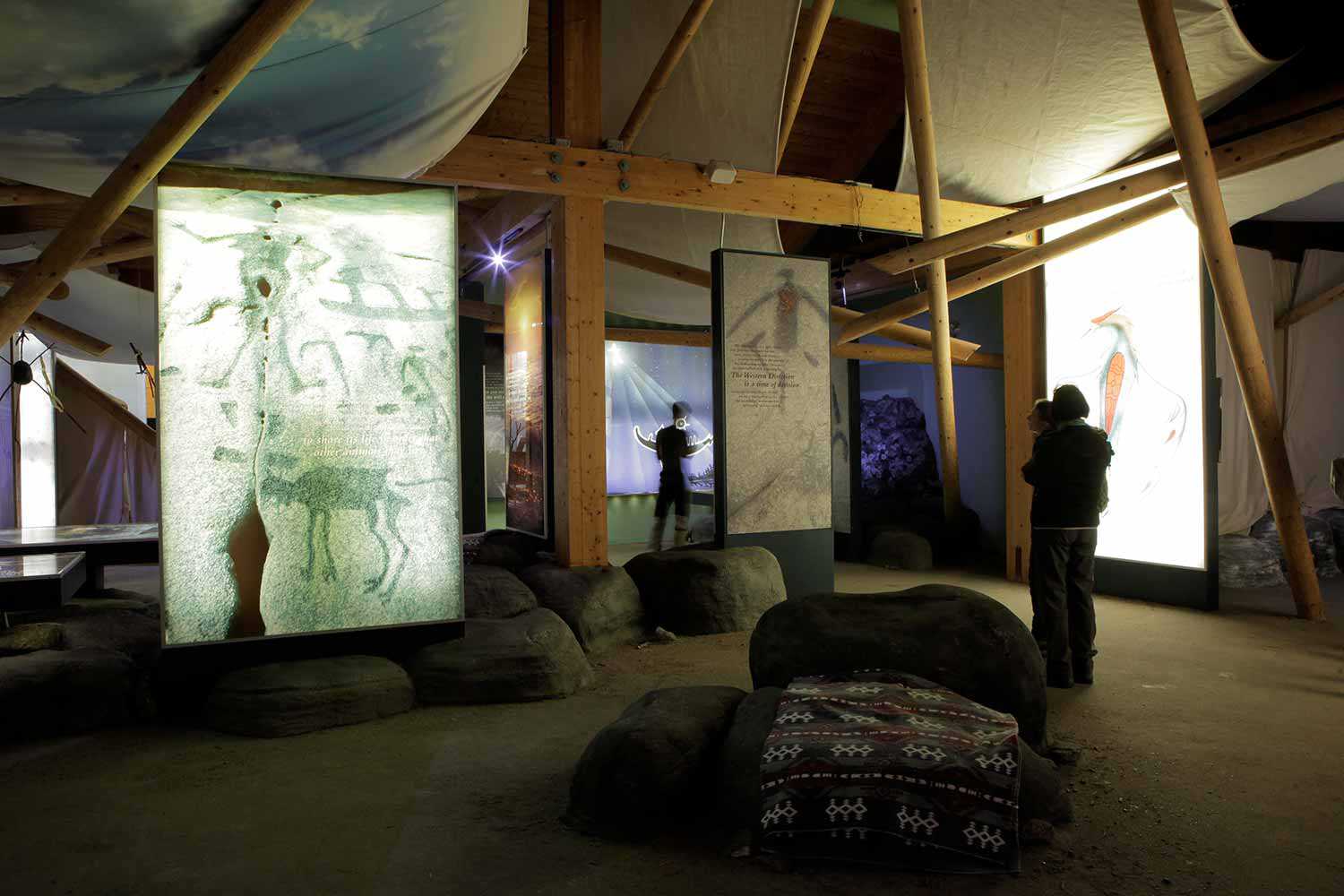

From the First People who for thousands of years conducted religious and cultural ceremonies at places they believed held spiritual significance, to subsequent arrivals who brought their own beliefs and values and congregated at the new places of worship they established, each phase of Ontario’s settlement and growth has enriched the province’s religious heritage.

Nearly 400 years ago, when the French arrived in what is now Ontario, they set out to establish political and trade relations with the First Nations. The French also attempted to persuade, sometimes successfully, the land’s inhabitants to adopt their Roman Catholic beliefs. Samuel de Champlain attended the first Roman Catholic mass celebrated in Huron country by Recollet Father Joseph Le Caron on August 12, 1615, at the Huron fortress of Carhagouha, four kilometres northwest of modern Ste Croix Roman Catholic Church in Lafontaine (today, the Carhagouha Cross marks the site).

In 1639, French Jesuit missionaries began construction of Sainte-Marie Among the Hurons, which became the first European settlement in Ontario, on the Wye River near Georgian Bay. Devastation from war and disease led the Jesuits to burn the settlement in 1649, but the French moved to the interior of the province and continued their political and trade activities and missionary work.

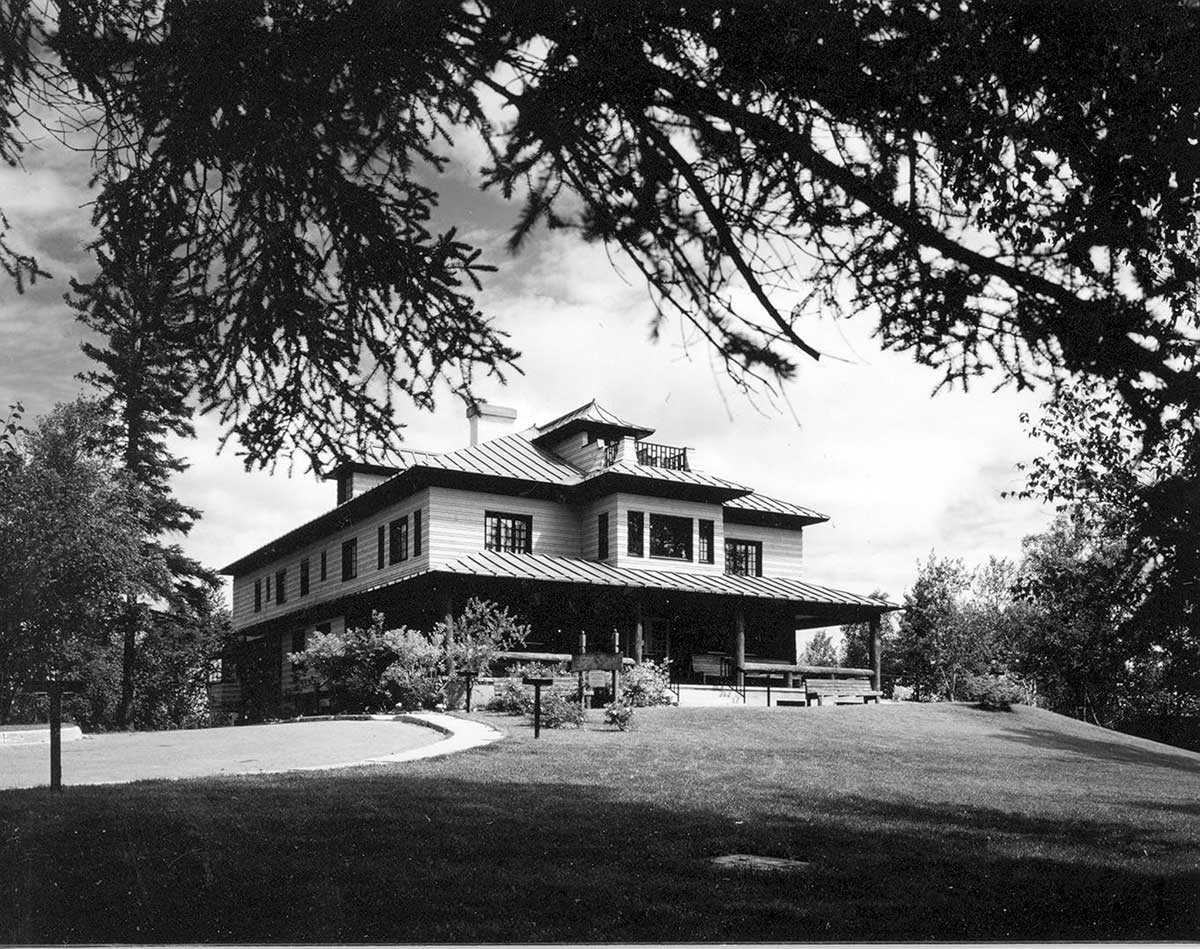

With the fall of New France in 1763, the French influence in Ontario diminished. No churches from the French era have survived in the province. Subsequent French-speaking settlers from France and Quebec, however, built communities and churches that preserved the legacy of French Roman Catholicism in Ontario. Notable examples include Assumption Church in Windsor, which contains a 1787 hand-carved wooden Baroque pulpit, the Martyrs’ Shrine in Midland and the Nativity Church in Cornwall.

Some of Ontario’s oldest churches date from the province’s Loyalist period. In 1783, following the American Revolution, American colonists who had remained loyal to the British Crown resettled in southern Ontario along the St. Lawrence River and Great Lakes, founding communities near Cornwall, Kingston, Niagara, Windsor and elsewhere. Their presence marks the beginning of the strong British influence on Ontario’s political, cultural and religious institutions.

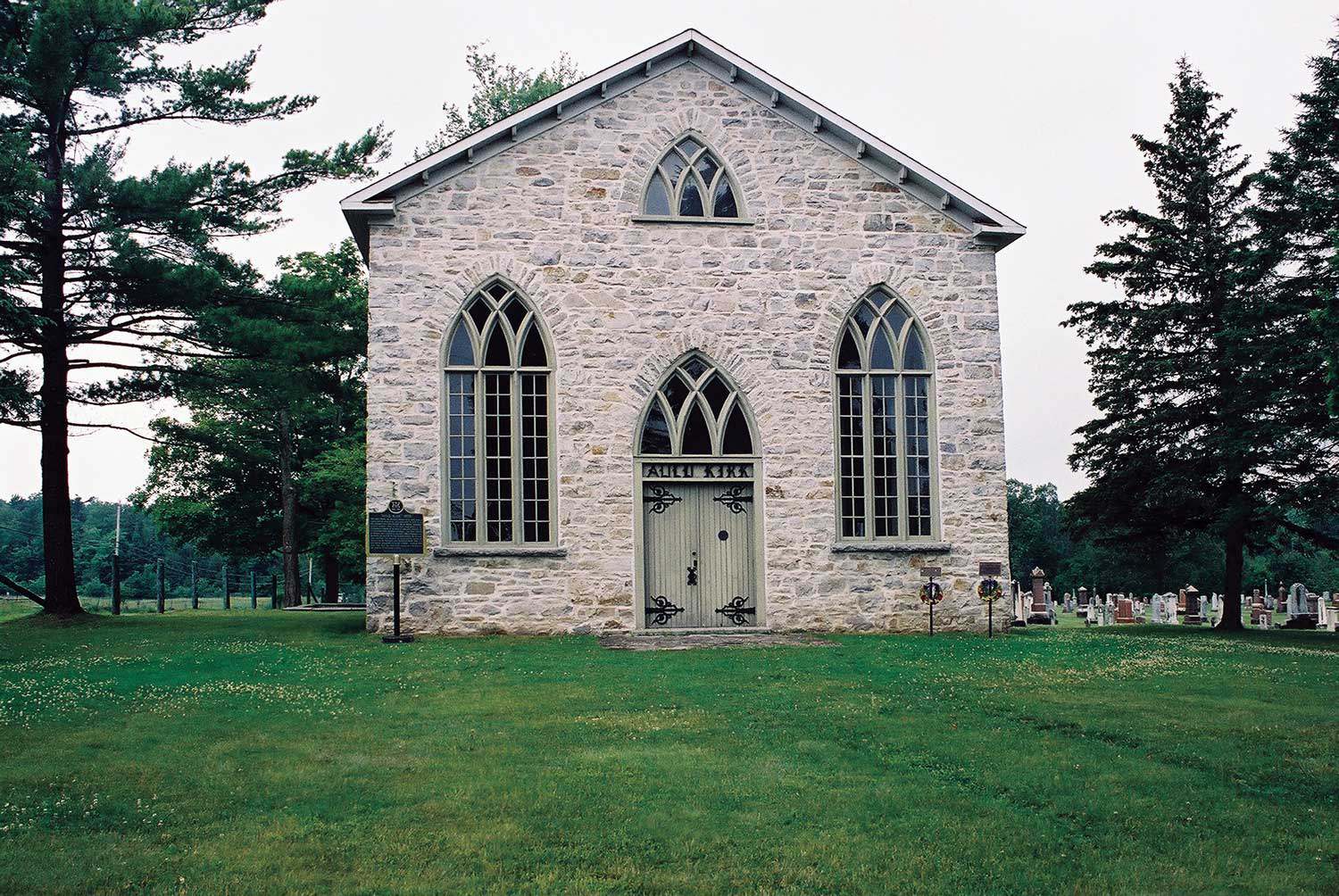

Loyalists were both Catholic and Protestant. The range of churches from the early 19th century reflects the diversity of their faith – the Anglican Blue Church in Augusta, St. Andrew’s Presbyterian in Williamstown, Hay Bay Methodist in Adolphustown and St. Andrew’s Roman Catholic in St. Andrew’s West. Some early churches served British military garrisons – such as Christ Church at Amherstburg, serving Fort Malden – and St. James-on-the-Lines Garrison Church in Penetanguishene. Another important example of an early Catholic church can be seen in the ruins of St. Raphael’s in South Glengarry.

Although the churches established during the early period of British rule were of different denominations, their congregants shared common linguistic, cultural and political experiences that brought them together. During the 19th century, for many British immigrants and Loyalists, religious activities were closely linked with loyalty and with political, economic and military pursuits.

Pacifist religious groups such as Mennonites and the Religious Society of Friends (Quakers) came to Ontario after the American Revolution to avoid military service and persecution, settling in the Quinte and Niagara areas. Additional Quaker settlements were established after 1800 in King Township, Northern Whitchurch Township, Yarmouth Township and Norwich. The Quakers promoted peace, temperance and social service, and took a leading role in the Underground Railroad. Their churches were simple undecorated wood structures that implied a rejection of the types of religious buildings erected by the larger Christian denominations. The Children of Peace or Davidites, who broke from the Quaker faith in 1812, established a particularly beautiful temple at Sharon in 1825-31. A notable example of an early Mennonite meeting house is the 1820 Reesor Meeting House in Markham.

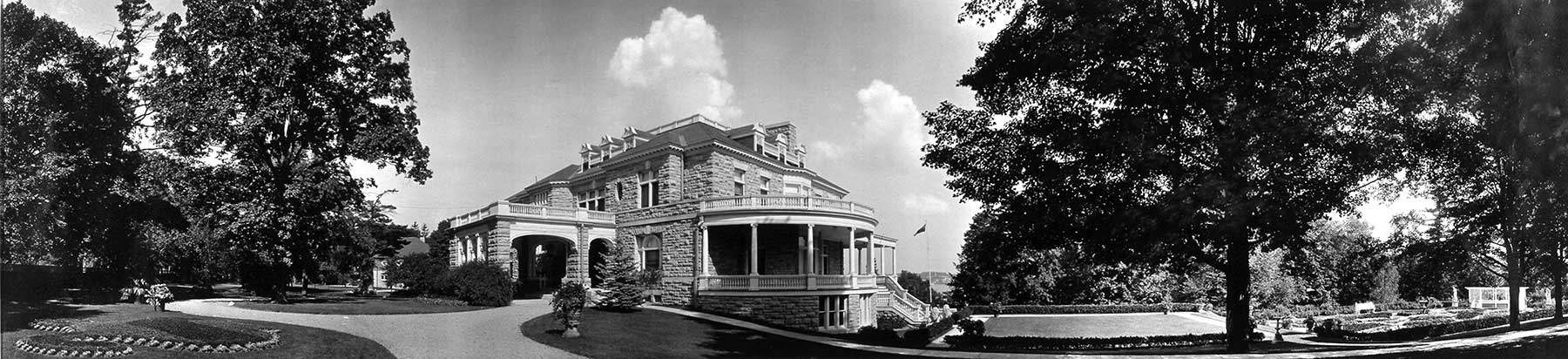

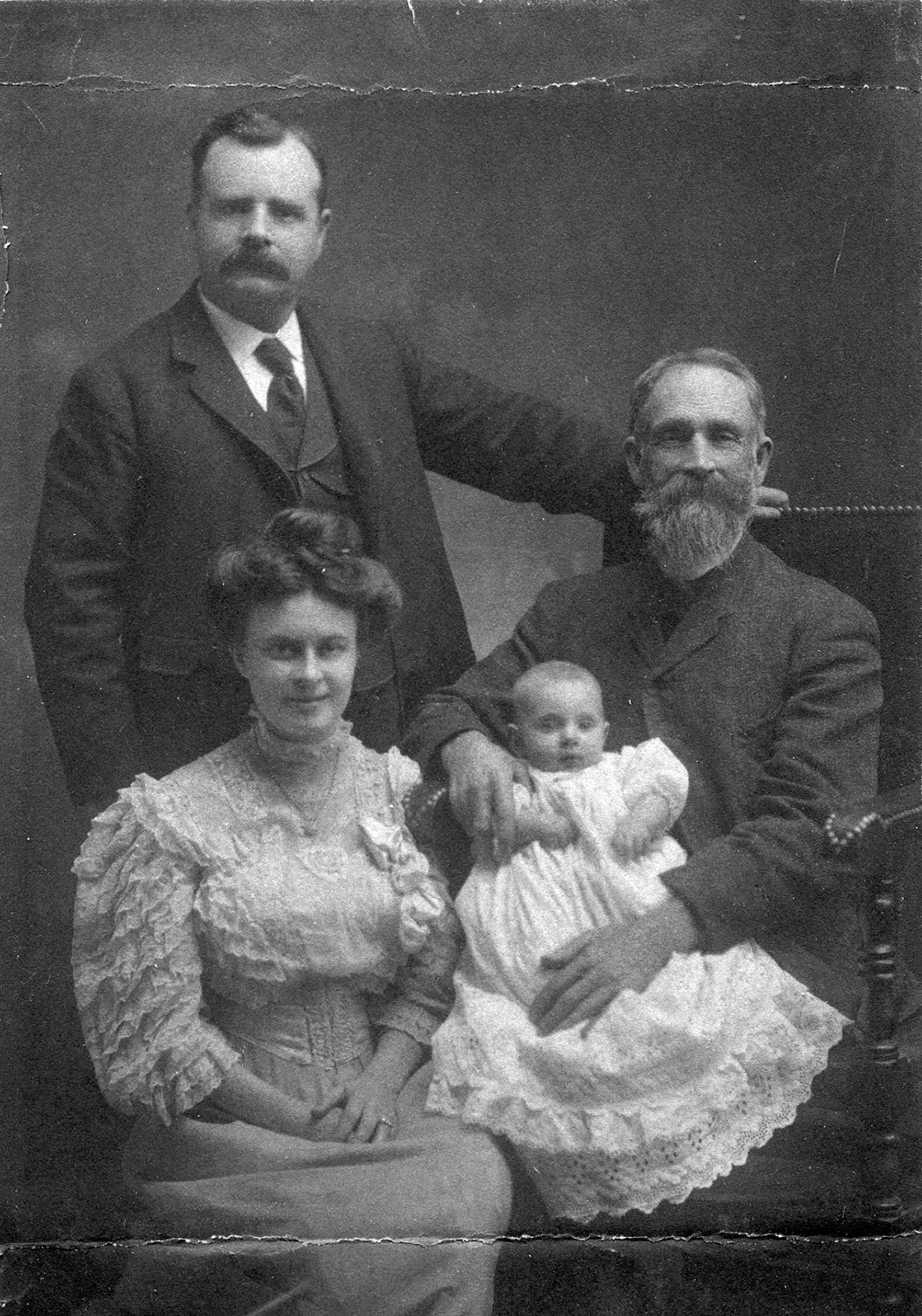

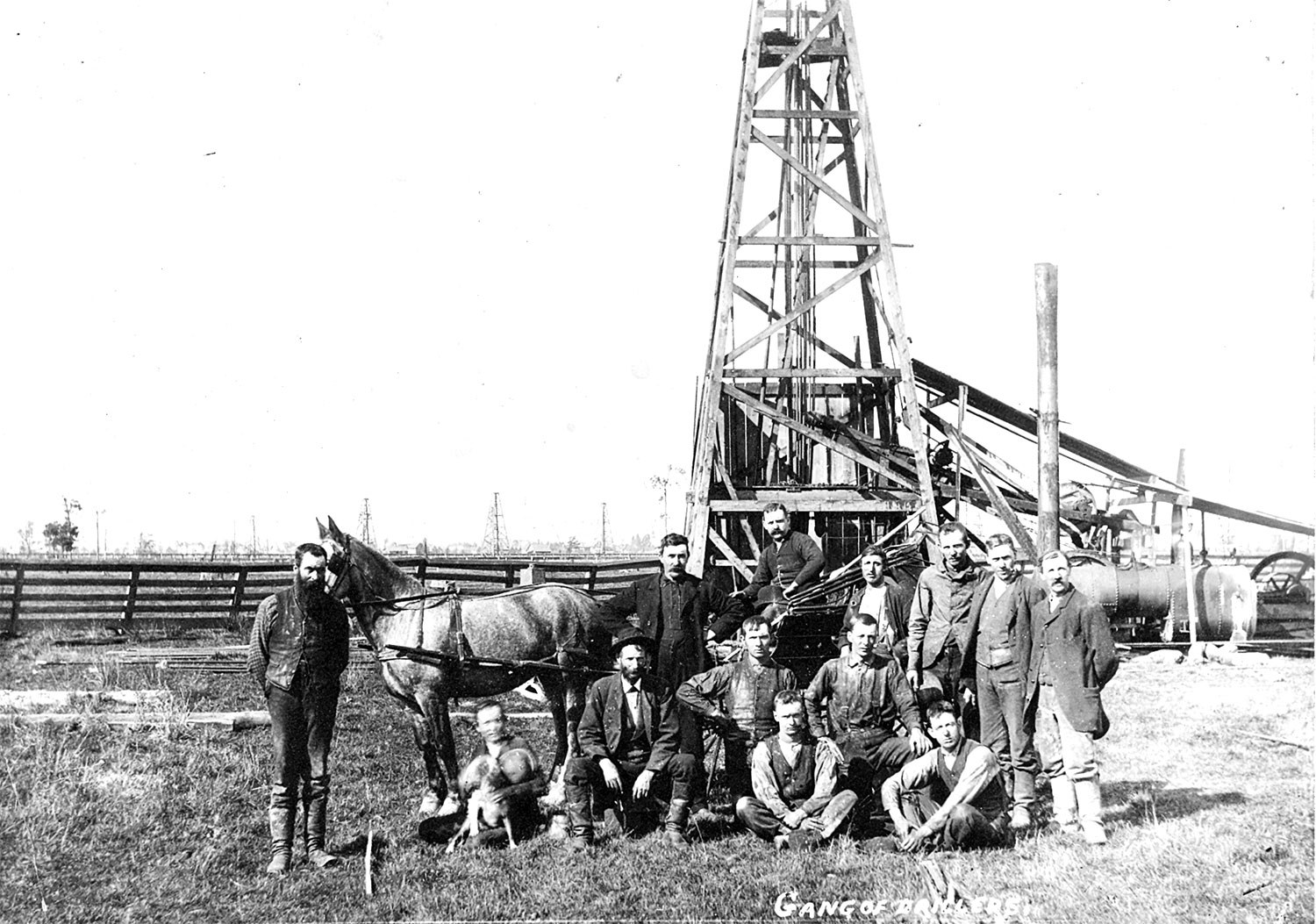

During the 19th century, new towns and villages developed throughout Ontario, spreading inland from the Great Lakes and major waterways. Large urban centres coalesced at places like Toronto, Kingston and London. Although agriculture remained important to Ontario, manufacturing and industry brought energy and drive to economic expansion. But it was people – successive waves of immigrants from Britain, the United States and parts of Europe – who fueled the province’s dynamic growth.

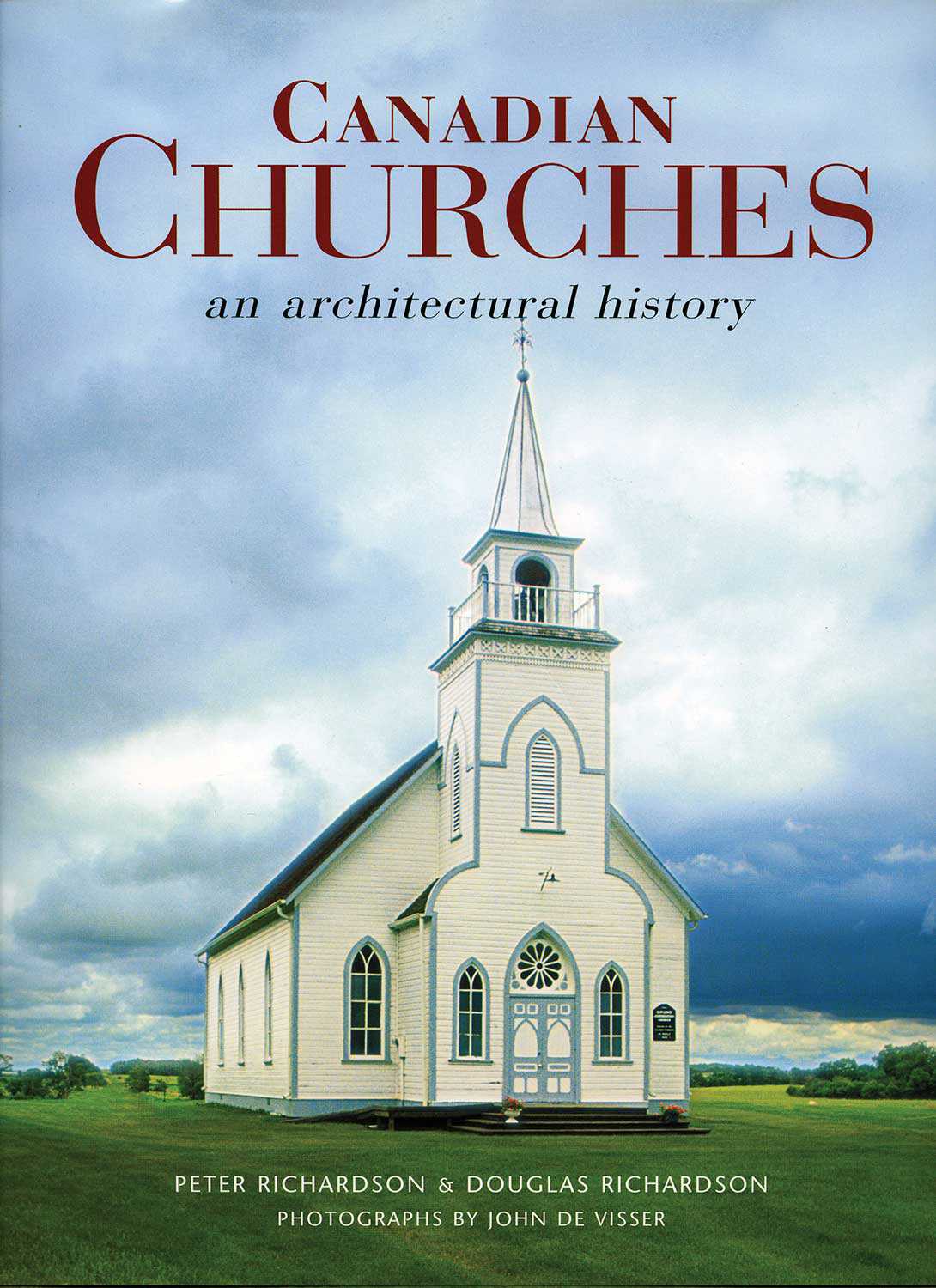

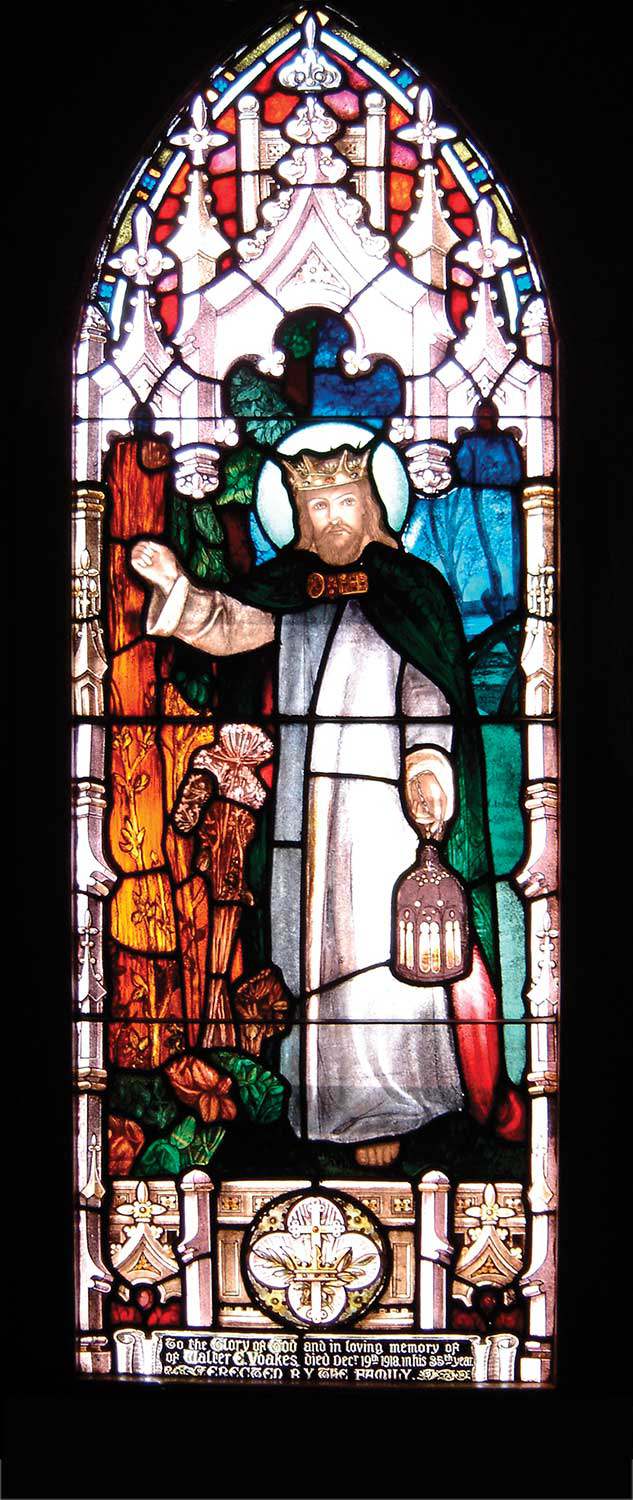

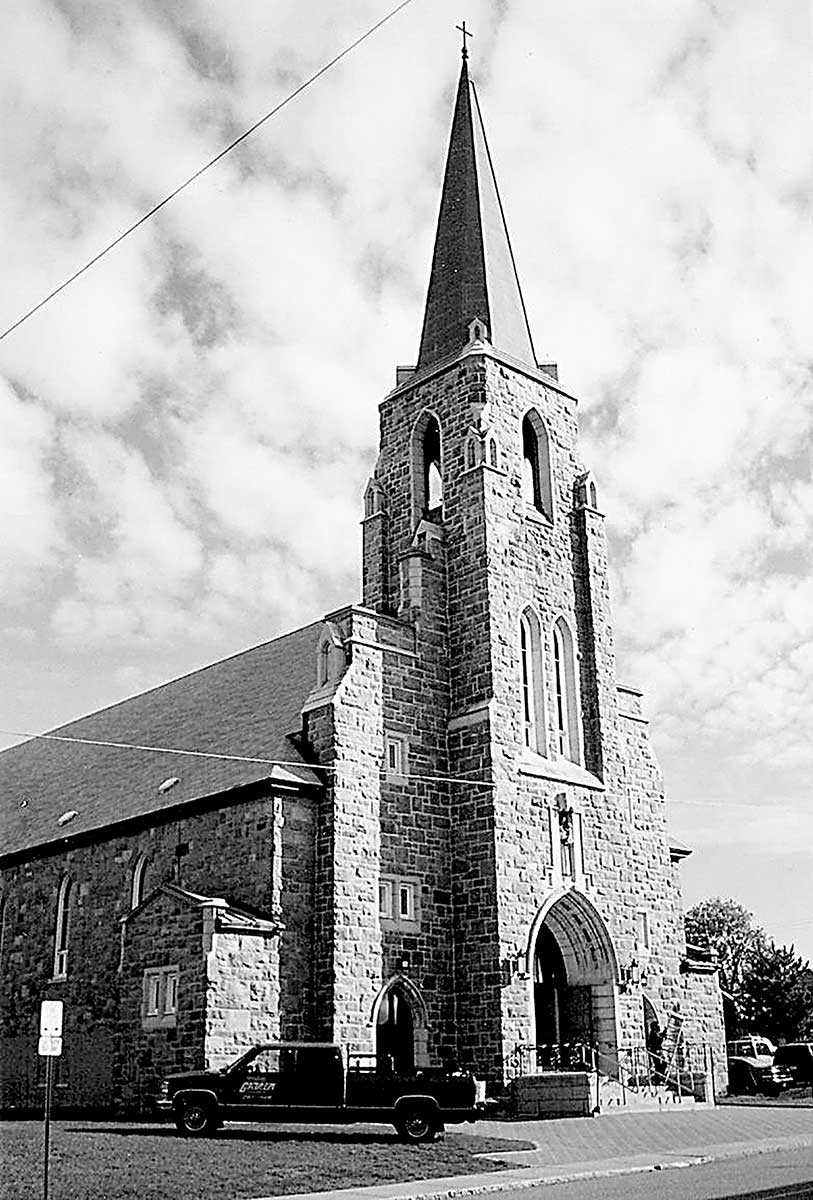

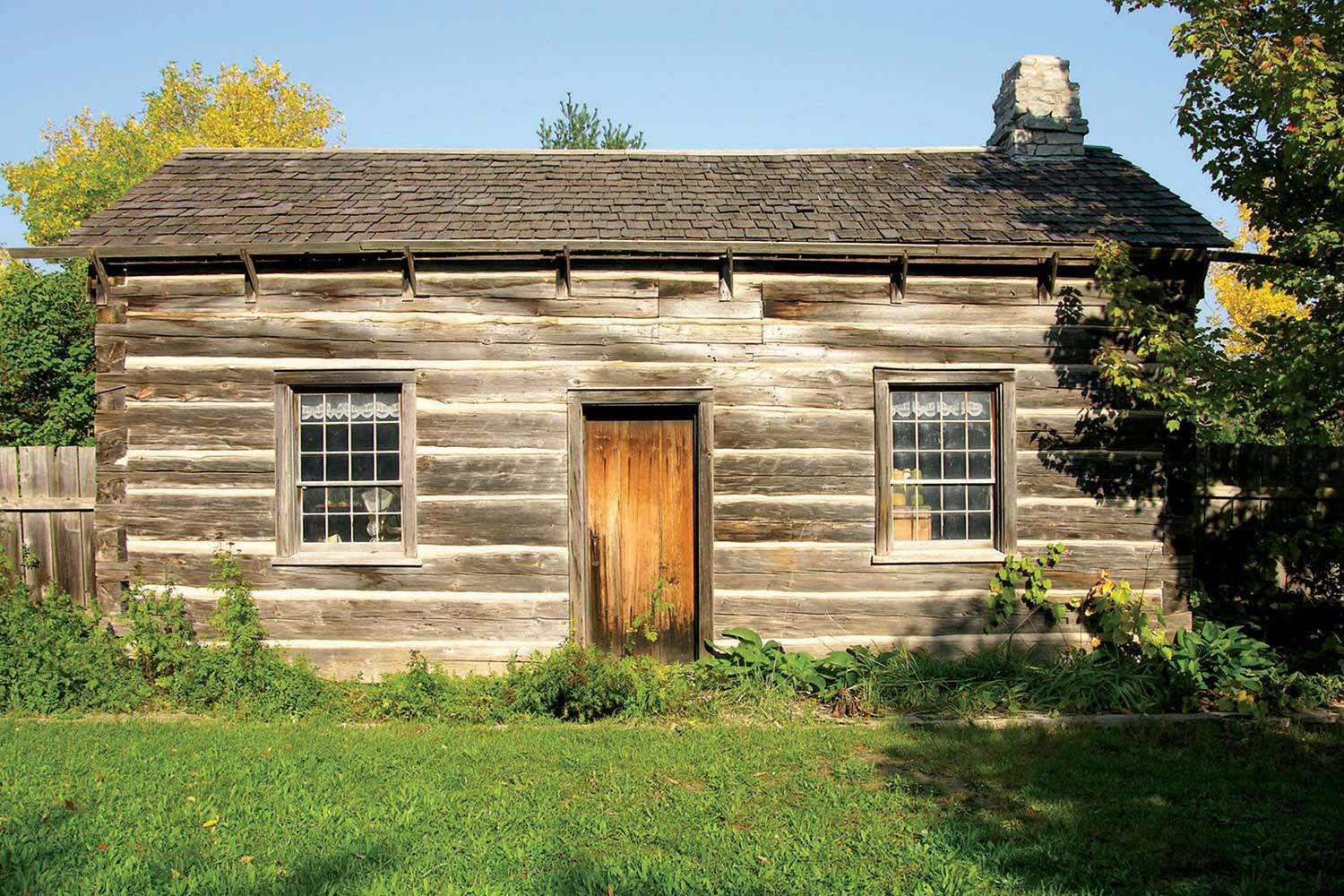

During this period, the population continued to be largely of British origin or descent, although Aboriginals, Blacks, French, Germans and Americans also figured prominently in the province’s history. Wherever people settled, they built churches – often as a priority. As communities prospered and grew, they replaced their first, usually rudimentary log or wood-frame churches with larger and more specialized buildings appropriate to the particulars of their faith. Anglicans erected piercing steeples, Presbyterians stout stone monoliths, Catholics tall prominent landmarks, Methodists modest wooden or brick buildings and so on. Although the face of religion in 19th-century Ontario was still largely British and Christian, its expression in places of worship was quite varied.

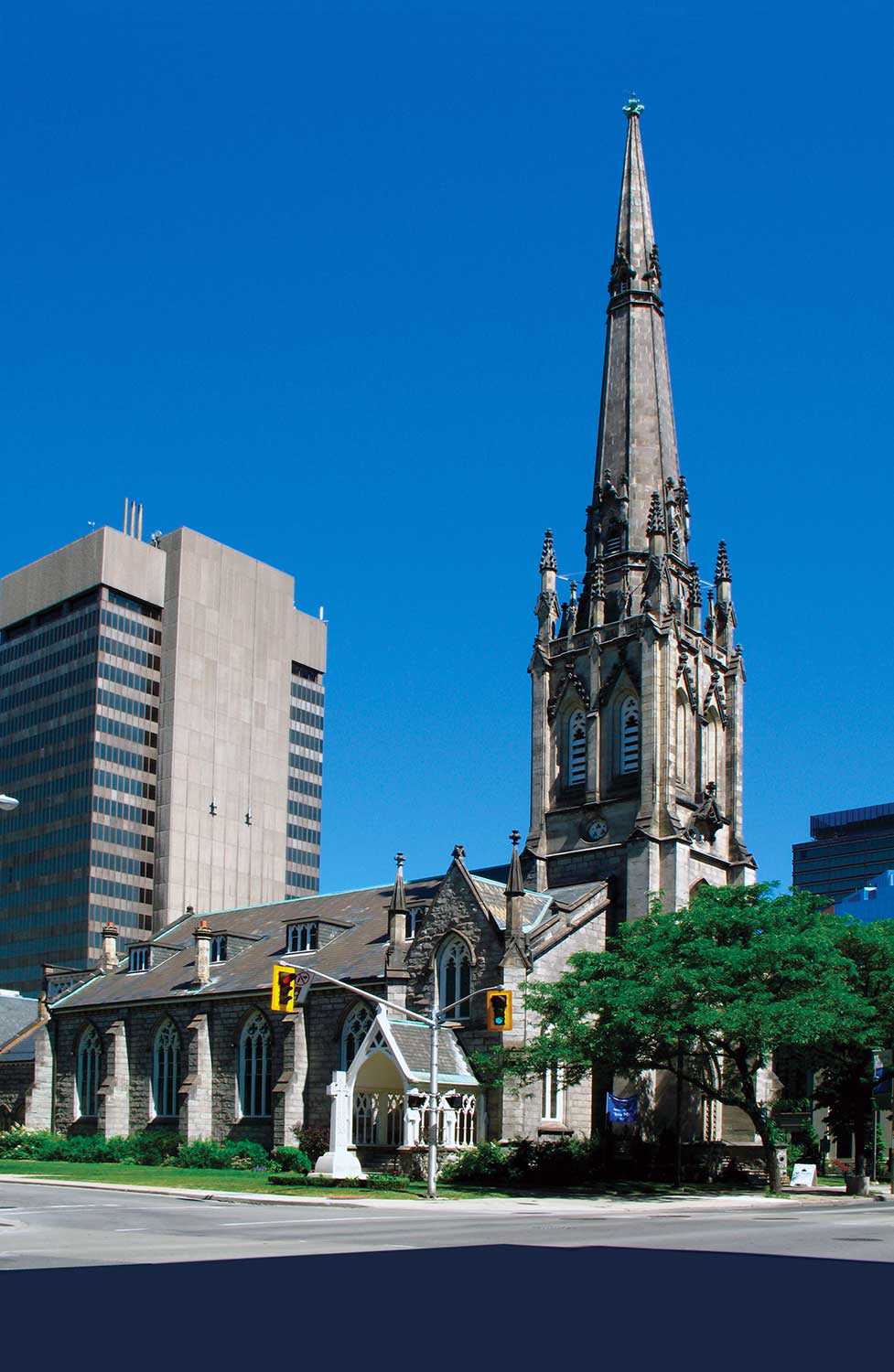

Some of Ontario’s most striking religious architecture stems from this period. St. James Cathedral in Toronto overlooks a stately public park. A number of churches in places like Brockville and Brantford flank county courthouses, helping to frame impressive public spaces. Others, such as those in Goderich, anchor downtown cores and main streets. Rural churches that stand as beacons of light amid furrowed fields include Marsh Trinity Anglican in Cavan-Monaghan Township and Lingelbach United in Perth East Township.

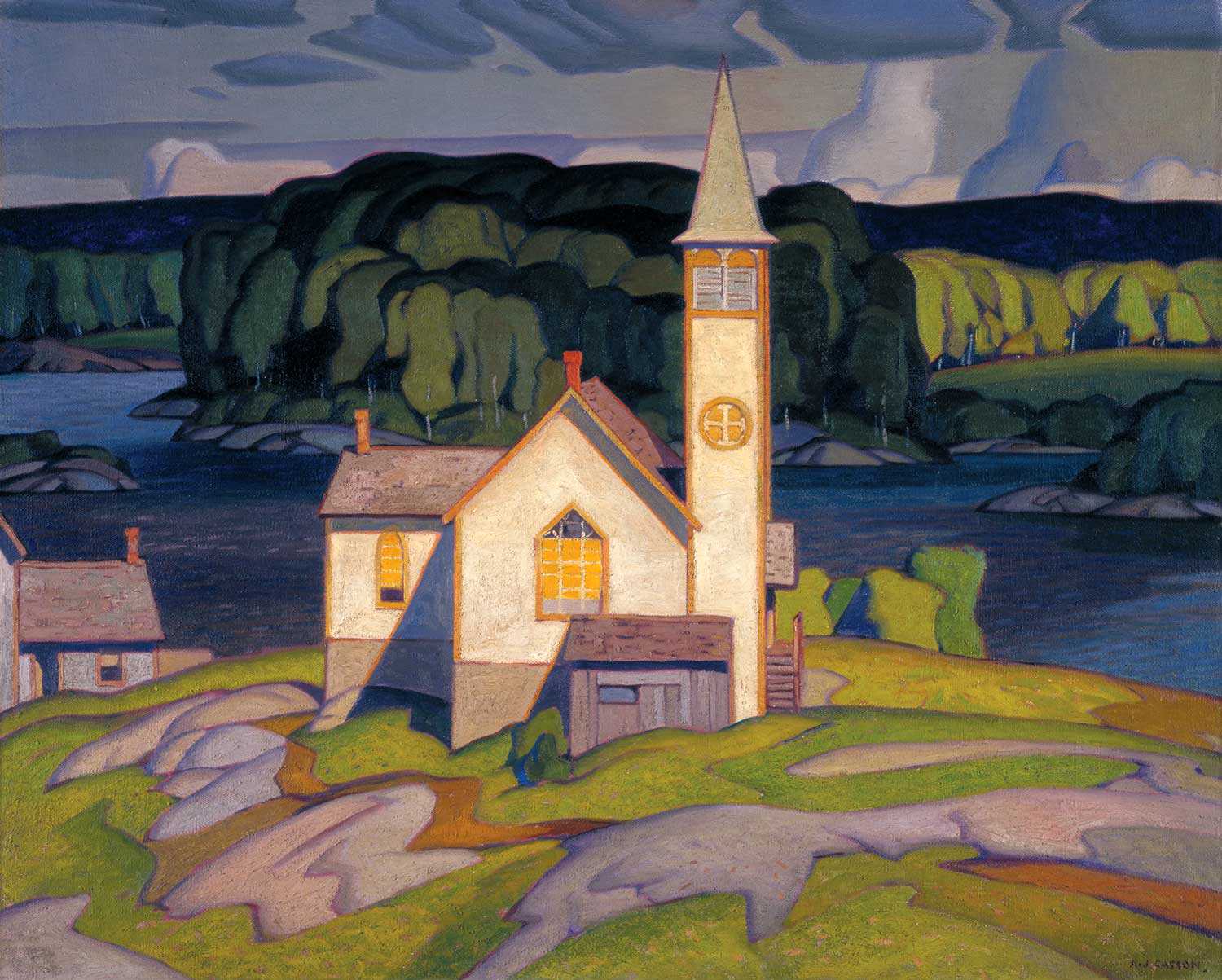

In central and northern Ontario – where towns developed around port lands, sprang up along railways or grew from industries such as mining or lumbering – churches were often seen as the focal point of community life and a counterpoint to vice and sin. In the port town of Owen Sound, the four churches at the intersection known as “Salvation Corners” were a stone’s throw from “Damnation Corners,” where four hotels once stood.

Many congregations established in the province’s early days have survived, even though their original places of worship have not. For instance, the first Jewish congregation in Ontario, Toronto Hebrew Congregation Holy Blossom, was founded in 1856. And St. John’s Evangelical Lutheran Church in South Dundas serves one of the oldest German parishes in Ontario, dating from 1784.

While early Canadian immigration policies typically favoured people from Britain and western Europe, at certain times during the 19th and 20th centuries Canada opened its doors to labourers from others parts of central and eastern Europe. Often these people had been driven from their homelands by political turmoil or other adverse conditions. Enticed to Canada by offers of free land and hopes of prosperity, they arrived to face new hardships. Many could not speak English or communicate with government officials. They were allotted land in remote areas, unreachable by road and sometimes unsuitable for farming. They endured poverty, hunger and cold. Although they came from different countries, spoke different languages and settled in different parts of Ontario, each group brought its own sense of community and cultural identity. Wherever they settled, they built churches and synagogues to worship in their own languages and according to their own faiths.

At Wilno in Renfrew County, Polish immigrants settling along the Opeongo Road established the Polish-speaking parish of St. Stanislaus Kostka in 1875. In 1895, St. Mary’s Roman Catholic Church in Wilno opened its doors. It serves Wilno’s Polish community to this day. Jewish immigrants from eastern Europe settled in west Toronto during the late 19th century, building the Knesseth Israel Synagogue in 1911. The Adath Jeshurun Congregation in Ottawa built its first synagogue in 1904. Like many early Jewish congregations, both Knesseth Israel and Adath Jeshurun worshipped in private homes or elsewhere until they could afford to build a place of worship. In 1930, Slovak immigrants settled at Bradlo in northern Ontario, where they built a Roman Catholic church in 1933. Italians, Portugese, Greeks, Macedonians and others arrived in successive waves of immigration, establishing churches in urban centres such as Toronto, Hamilton, Windsor and elsewhere. Santa Inês-St. Agnes Church in Toronto was built in 1913 to serve an Italian community. Today, it serves a Portuguese community. In northern Ontario, Ukrainian immigrants founded churches at Timmins, Kirkland Lake and Sudbury, and Finnish immigrants established places of worship in the Thunder Bay district. These immigrant groups dramatically expanded Ontario’s religious heritage.

More recently, Canada has welcomed immigrants from around the world, bringing an exciting diversity of faith groups to Ontario. The London Muslim Mosque opened in 1964 as Ontario’s first purpose-built mosque. The Vishnu Mandir in Richmond Hill is the first purpose-built and architecturally accurate Hindu temple in the province. The Shiromani Sikh Society built Ontario’s first permanent gurdwara in Toronto in 1969. Many Buddhists have adapted homes and storefronts to house places of worship – the Riwoche Tibetan Buddhist Temple in Toronto is located in a former piano showroom. Christian congregations of Chinese, Korean and Vietnamese Canadians are revitalizing older churches.

Today, Ontario’s places of worship represent not only the province’s rich religious heritage, but also the extraordinary cultural diversity of its successive inhabitants, vibrant people whose traditions and values continue to enliven and enhance our society.

![J.E. Sampson. Archives of Ontario War Poster Collection [between 1914 and 1918]. (Archives of Ontario, C 233-2-1-0-296).](https://www.heritage-matters.ca/uploads/Articles/Victory-Bonds-cover-image-AO-web.jpg)

![The family of Simon Aumont. Only Simon himself and Irène (seated, holding a doll), survived the great fire that devastated the region in 1916, Val Gagné (Ontario), [before 1916]. University of Ottawa Centre for Research on French Canadian Culture, TVOntario archive (C21), reproduced from the collection of Germaine Robert, Val Gagné, Ontario.](https://www.heritage-matters.ca/uploads/Articles/Frenette-Ph23-VG-3-web.jpg)

![Students demonstrating against Regulation 17 outside Brébeuf School on Anglesea Square in Ottawa’s Lowertown, in late January or early February, 1916 / [Le Droit, Ottawa]. University of Ottawa, Association canadienne-française de l’Ontario archive (C2), Ph2-142a.](https://www.heritage-matters.ca/uploads/Articles/Cecillon-Ph2-142a-web.jpg)