Browse by category

- Adaptive reuse

- Archaeology

- Arts and creativity

- Black heritage

- Buildings and architecture

- Communication

- Community

- Cultural landscapes

- Cultural objects

- Design

- Economics of heritage

- Environment

- Expanding the narrative

- Food

- Francophone heritage

- Indigenous heritage

- Intangible heritage

- Medical heritage

- Military heritage

- MyOntario

- Natural heritage

- Sport heritage

- Tools for conservation

- Women's heritage

Ontario’s medical legacy

In the mid-19th century, a typical doctor ran a solo practice, often making house calls on horseback or by sleigh. Many treatments offered relief for symptoms, but cures belonged to nature. The spectre of infections – diphtheria, whooping cough, measles, scarlet fever and smallpox – was ever present. Few specialists were available; a doctor delivered babies, set fractures, pulled teeth, mixed medicines and comforted those in need. Many patients could not pay medical bills and the concept of vacations had yet to be invented. Much has changed in the last 150 years.

Canada’s first training school for nurses, c. 1875 (St. Catharines). Canadian Museum of History, 2001-H0006.4, IMG2008-0633-0021.

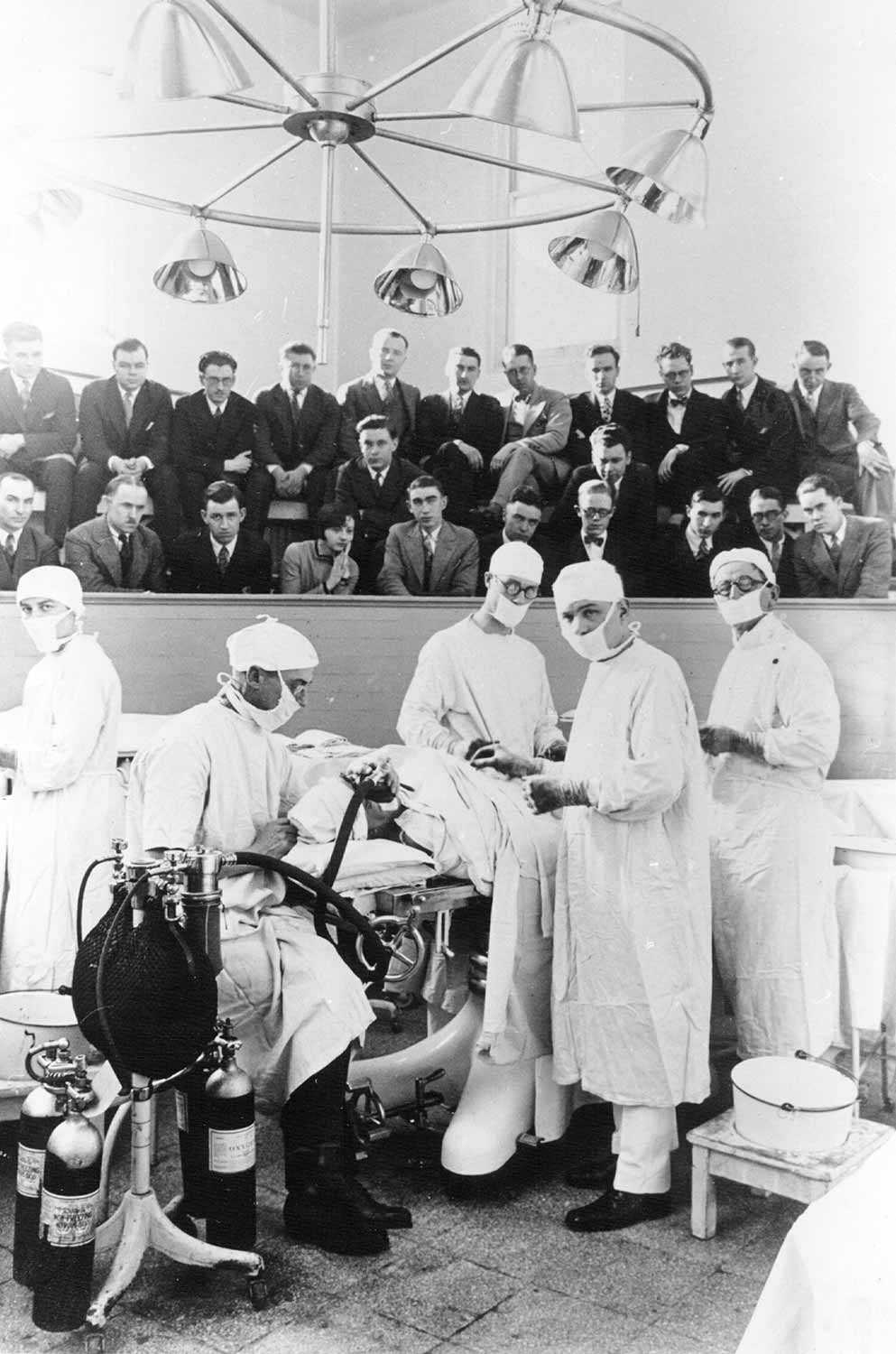

Until the later 19th century, most Ontario practitioners studied in Britain or the United States. At least three medical schools in Ontario, however, supplied skilled practitioners to local communities: Duncombe’s in St. Thomas (1824), Rolph’s School (1843) and King’s College (1843), both in Toronto. Physicians communicated with each other around the world through journals that featured original research and reports of innovations. Through these journals, Ontario doctors were able to apply the great 19th-century discoveries – anesthesia by 1847, antisepsis by 1867 and germ theory by 1882. The latter prompted the creation of a formal department of public health and the rapid incorporation of microscopy and bacteriology into clinical practice and education.

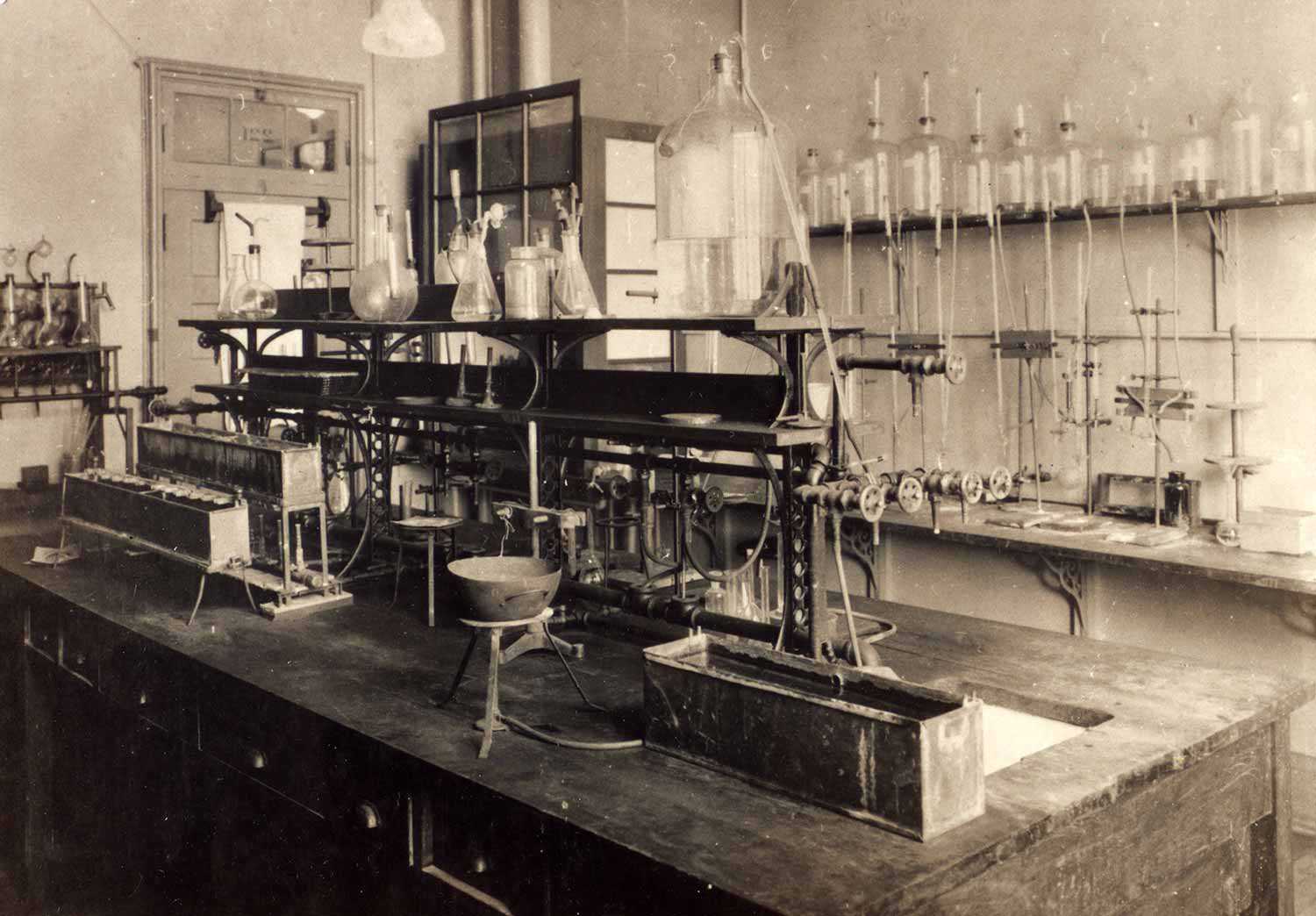

But some innovations are wholly Canadian, and many were from Ontario. Arguably, the most famous was the discovery of insulin by Drs. Frederick Banting, Charles Best, J. Bertram Collip and J.J.R. Macleod. Their achievement provided an effective treatment (not cure) for a deadly disease that was, and still is, all too common. For their efforts, they won the 1923 Nobel Prize.

By 1929, and for the next two decades, Best and his colleagues worked on finding safe uses for the blood thinner heparin. Although it had not originally been a Canadian discovery, they championed its applications in treating phlebitis, gangrene and pulmonary embolus. Heparin also meant that blood could be kept from clotting on contact with instruments, making it an essential step in advancing the possibilities of cardiac surgery.

In Toronto, a surgical team led by Wilfred G. Bigelow worked to repair heart defects. They had to find a way to decrease the body’s need for oxygen in order to stop the heartbeat for short periods without damaging tissues. Inspired by the slowed metabolism of hibernating animals, they induced hypothermia to lower body temperature, allowing extra time for operating. This creative 1950s technique was eventually superseded by the advent of the heart-lung bypass machine, which took over the job of pumping blood while the heart was stopped.

The Second World War ravaged hundreds of young adults. Hoping to rehabilitate spinal-cord-injured soldiers, neurosurgeon Edmund H. Botterell and physiatrist Albin Jousse created a special program at Toronto’s Lyndhurst Lodge in 1945. Their mission was to restore the disabled soldiers to active life through physical and mental therapy. The focus expanded to include civilian patients with other disabilities, and Lyndhurst eventually evolved into a major research institute for rehabilitation.

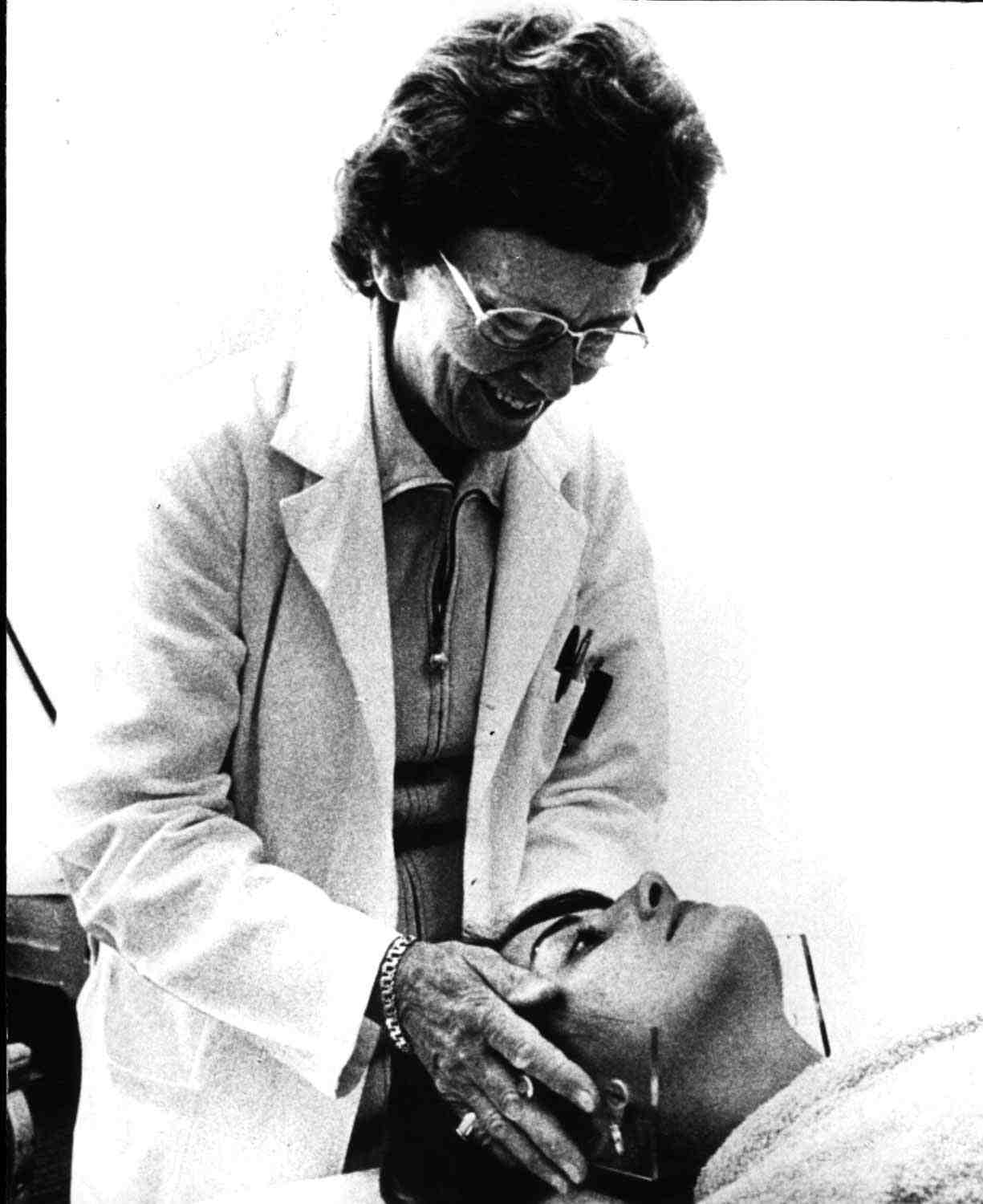

In the care of mothers and children, several Ontario initiatives were firsts for Canada, if not the world. Elizabeth Bagshaw established a birth control clinic in Hamilton in 1932. Vaccination of infants against the infectious scourges of the previous century became a requirement for admission to public school. Additionally, Toronto’s Hospital for Sick Children witnessed the advent of brilliant surgical procedures for congenital heart disease and dislocated hips.

Following the observations of Pierre and Marie Curie, radioactive substances were soon applied to the treatment of cancer. From the 1930s, the town of Port Hope hosted the Eldorado Company for refining radium. Inserted into needles and other devices, radium treated malignant tumours in all parts of the body. The results were impressive. Its byproducts include uranium, which led to Port Hope’s involvement in the Manhattan project to produce the atomic bomb. Eldorado brought jobs and prosperity to Port Hope. Later, citizens learned of the dangers of radiation, and following 20 years of controversy, radium production ceased. Uranium production continues but the safe disposal of nuclear waste remains a significant challenge.

The province created the Ontario Cancer Treatment and Research Foundation in 1943 (OCTRF, now Cancer Care Ontario) to coordinate access to the new treatments of radiation and chemotherapy, and to promote research. In 1951, under the auspices of the clinic in London, the province competed with Saskatchewan for the first installation and use of a cobalt-60 unit. Whichever province deserves that honour, Ontario succeeded in luring the brilliant teacher-scientist Harold E. Johns from Saskatoon to Toronto, where he authored the definitive book on radiation physics and inspired generations of young physicists and doctors.

A little-known Ontario achievement in cancer treatment was the 1958 isolation of vinca alkaloids from the periwinkle plant in the London laboratory of Robert Noble, by his chemist, Charles Beer, and their assistant, Halina Robinson. Jamaicans had sent dried leaves of the vinca plant to Canada, hoping it would prove to be a source of oral insulin. Instead, its purified extracts – vinblastine and vincristine – became drugs that are still widely used and have long been recognized as a cure for childhood leukemia.

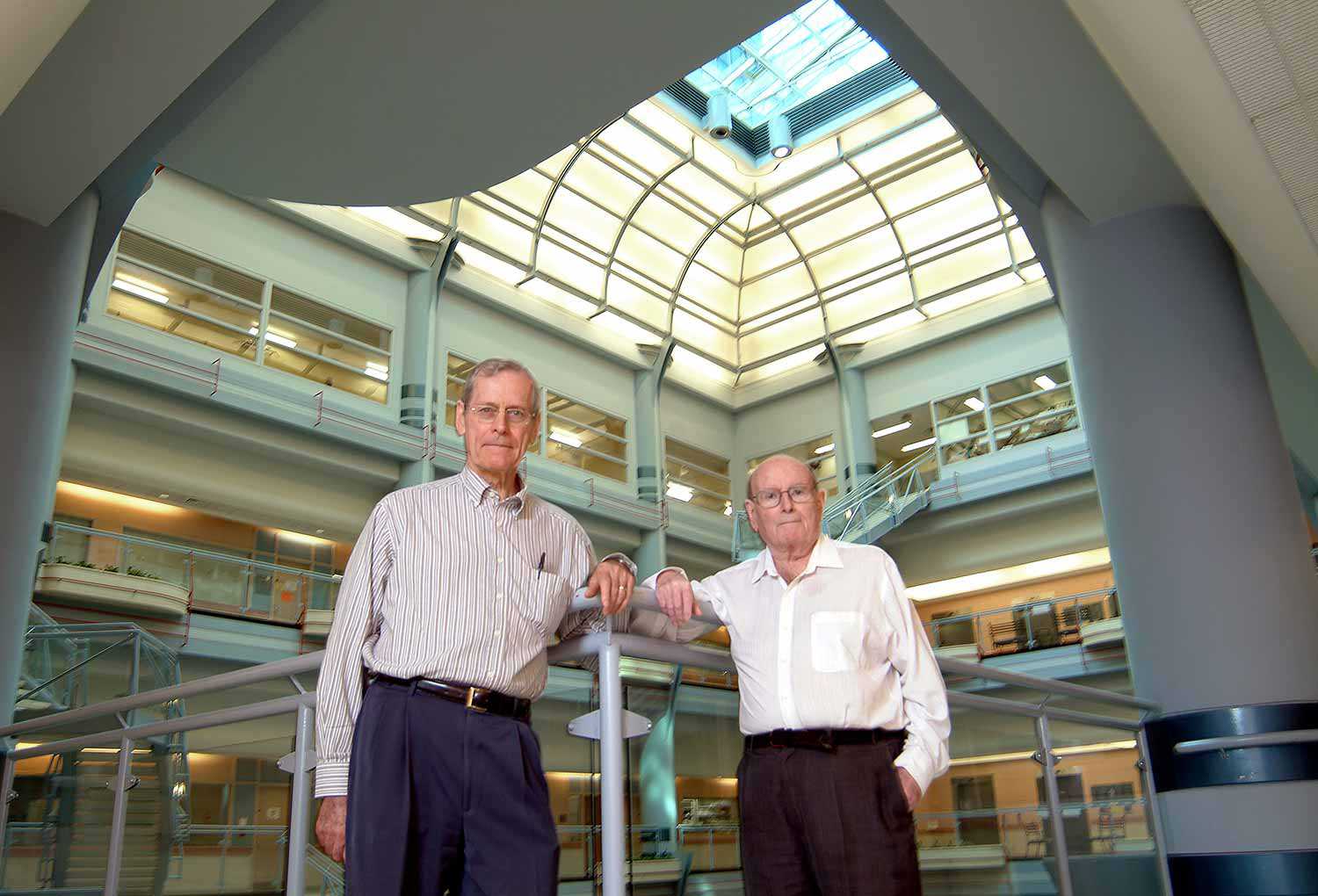

Another research achievement came in 1963 from Ontario Cancer Institute (OCI) scientists James Till and Ernest McCullough, who identified stem cells. Among the multiple applications of their work are the scientific foundations of the bone marrow transplantation developed by American Nobel laureate, E. Donnell Thomas. Decades later, OCI scientist Tak Mak cloned the T-cell receptor and pioneered research in genetically altered mice. His achievements have garnered multiple awards and inspired thousands of scientists around the globe.

The array of treatments and claims of manufacturers led McMaster’s David L. Sackett and Gordon H. Guyatt to argue for a more judicious use of scientific information. They recommended careful use of randomized, controlled trials – preferably double-blind – to evaluate changes in medical practice and construction of guidelines. This movement came to be called evidence-based medicine, a term coined by Guyatt in 1992. It now pervades all aspects of clinical science on an international scale.

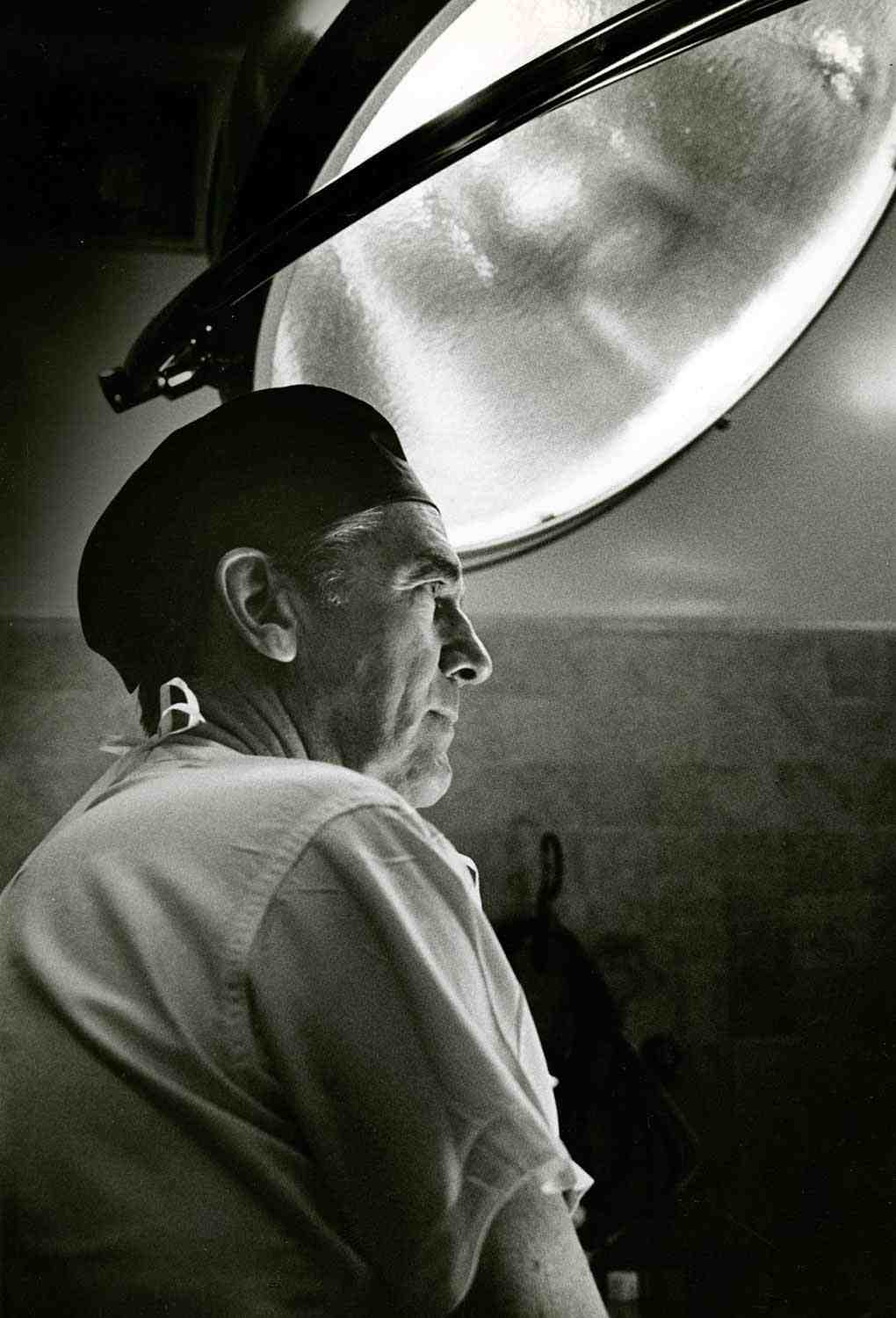

The first successful hand transplant in Canada took place at Toronto Western Hospital on January 12, 2016. Dr. Christian Veillette (right), orthopedic surgeon, looks at an X-ray to ensure proper alignment of the patient arm and donor arm as they are fused together. Photo courtesy of the University Health Network.

Ontario also pioneered innovations in health-care delivery. For example, psychiatric hospital beds were reduced by 80 per cent from 1960s levels; what had once been 16 residential homes for the mentally disabled were closed by 2009. Slow to conform to the Canada Health Act (1984) and following the 1986 doctors’ strike, the province made strides in developing policies around hospital and home care that reflect local needs and wise use of resources. For example, between 1996 and 2000, the Health Services Restructuring Commission mandated the elimination of more than 40 hospitals by closure or merger, and an increase in home care services. Similarly, primary care reform saw numbers of family physicians paid by traditional fee-for-service plunge from 95 per cent in 2000 to 28 per cent in 2013. Along similar lines, the Local Health Integration Network (LHIN) was created in 2007 to enhance community involvement in planning.

In terms of education, Canada’s first school for the training of lay nurses opened in St. Catharines in 1874 and continued for a century. In 1897, Lady Aberdeen, wife of the then-Governor General, launched the Victorian Order of Nurses. Although the program stretched from coast to coast, sites quickly appeared in Ottawa, Toronto and Kingston, and cottage hospitals were built in isolated areas. Nurses who took on remote jobs launched the nurse-practitioner and midwifery programs that came to Ontario in 1972 and 1993 respectively.

Over time, six medical schools became affiliated with Ontario universities. The problem-based-learning format of education used at McMaster medical school from its 1965 inception is now widely copied across the developed world, and is often wrongly attributed to Harvard Medical School. The newest, the Northern Ontario School of Medicine, opened in 2005 in both Sudbury and Thunder Bay.

It emphasizes partnering with First Nations populations and mandates month-long experiences for its students in Indigenous communities.

Since the 1986 doctors’ strike, a collaborative effort between Ontario medical schools developed a set of criteria to address what citizens expect from their doctors. Roles went beyond the predictable goals of scientific knowledge and technical skill. Funded by the philanthropic Associated Medical Services (AMS), this program was adopted by the Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Canada to become the basis of the CanMEDS competencies, a program that influences undergraduate and postgraduate medical education internationally. AMS also created the Jason A. Hannah Chairs for the History of Medicine in Ontario medical schools, more recently extended to other provinces. This gift emphasizes the role of history and humanities in clinical education, and makes us the envy of the medical history community.

In comparison to her colleague of 150 years ago, an Ontario practitioner now leads a busy life, but she often shares the load with a team. She can rely on many effective treatments and specialists. Her patients are immunized against infection and can expect cures and comfort for ailments, and they do not face unaffordable bills. She looks forward to continuing to learn about innovations that have been evaluated through robust clinical trials. But their stories fascinate and remind us of how they have improved quality of care and life for us all.