Browse by category

- Adaptive reuse

- Archaeology

- Arts and creativity

- Black heritage

- Buildings and architecture

- Communication

- Community

- Cultural landscapes

- Cultural objects

- Design

- Economics of heritage

- Environment

- Expanding the narrative

- Food

- Francophone heritage

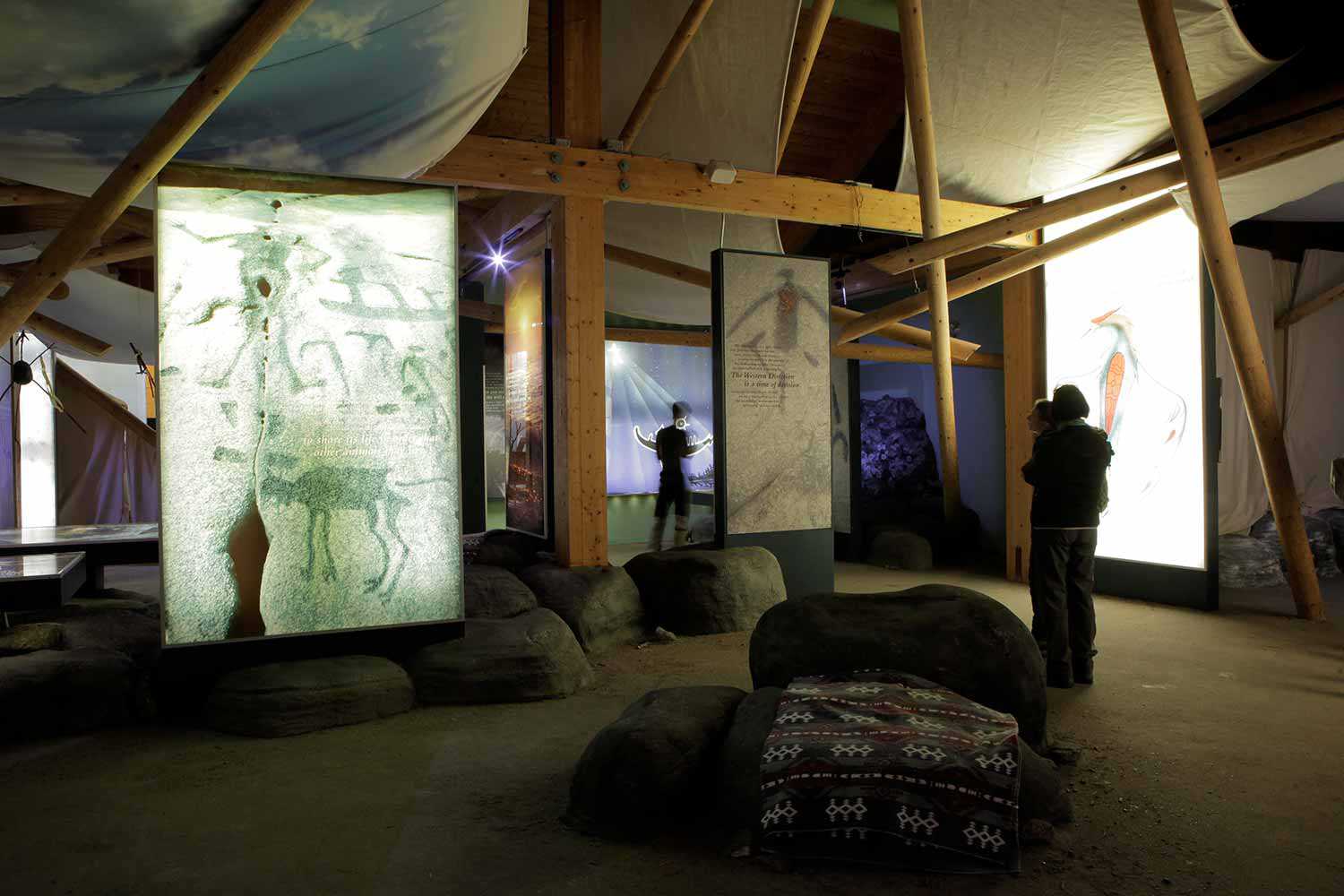

- Indigenous heritage

- Intangible heritage

- Medical heritage

- Military heritage

- MyOntario

- Natural heritage

- Sport heritage

- Tools for conservation

- Women's heritage

How I became a journalist

Published Date: 20 Mar 2019

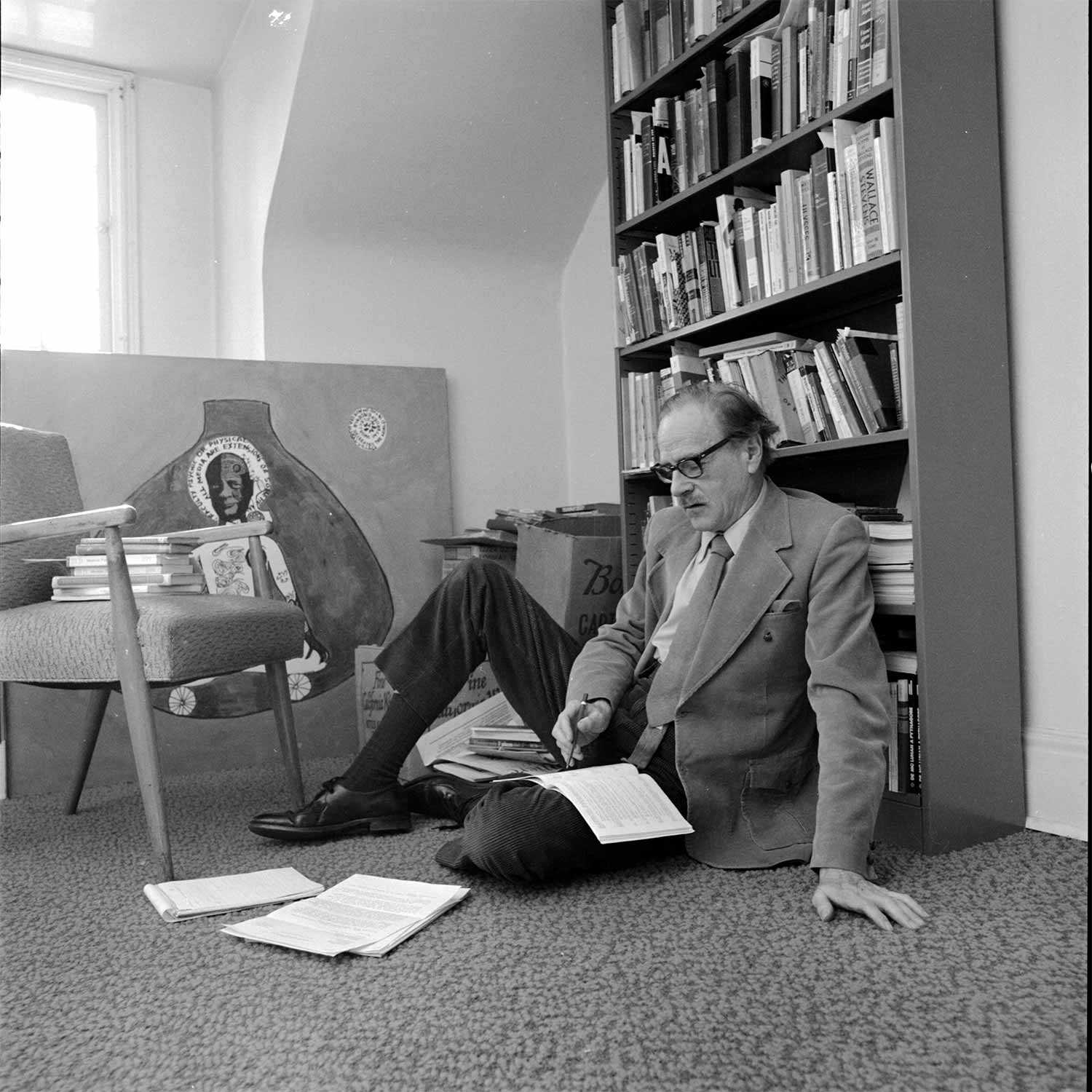

Whenever I’m asked how my career started, I usually say that it was an accident. I never studied journalism. I wanted to be an historian. In fact, I was planning to write a doctoral thesis about Harold Innis, a Canadian economic historian who wrote books about fur traders, and cod fishers, and loggers, and people involved in other primary resource extraction. He developed something called the “Staples Thesis,” and near the end of his career he started writing books like The Bias of Communication. This strange twist confounded and confused most conventional historians, but it fascinated me. Apparently, it also caught the attention of Marshall McLuhan. In the preface to The Gutenberg Galaxy, McLuhan wrote that his own work was “no more than a footnote to the work of Harold Innis.” I was enrolled at the University of Toronto, so I walked from Robarts Library (home of the Innis papers), across Queen’s Park, to St. Michael’s College. I knocked on the door of McLuhan’s office. It was 1976. He was at the height of his fame. I was a lowly graduate student from a different department. I had deluded myself into hoping that he might agree to work with me and act as an outside advisor for my thesis.

I was also terrified.

Marshall opened the door and invited me in. His office was cluttered, in a very friendly sort of way. There were shelves of books dominating every wall that wasn’t a window, and there were open books on all available horizontal surfaces. It was obvious that he’d been working, but he asked how he could help me. I told him about my thesis proposal – an intellectual biography of Harold Innis. He asked me which university department had accepted this proposal. I answered, “History.”

He asked whether they’d be open to outside advisors from other disciplines, and before I had a chance to tell him that I’d carefully examined the academic regulations, he voluntarily offered that he’d love to help me with my thesis.

Our conversation that first day lasted several hours. We talked mostly about Innis, with characteristically McLuhanesque detours into pop culture, rock music, contemporary politics and university gossip. By the time I left, I had agreed to prepare a reading list. He agreed to meet every couple of weeks, to discuss several books. My main focus would be preparation for a comprehensive exam at the end of a year, but I’d get periodic breaks to discuss Media Theory with “the guru.”

Those sessions were infinitely more interesting than anything I was doing in the History Department. I attended all of the compulsory seminars and did the required reading. I ultimately passed the comprehensive exam. It was time to turn my attention to the thesis, but first, there was a meeting with my academic supervisor.

Paul Kennedy hosted CBC Radio’s long-running nightly show called IDEAS for 20 years. He has been retired as of June 2019.

His office was just as messy as Marshall’s, but considerably less friendly. While reaching into a filing cabinet, and pulling out a red manilla folder, he announced that, “The graduate committee had a couple of issues with your thesis proposal …” He opened the file. “The first problem is the proposal itself. It’s way too ambitious.”

“It’s what I want to do!” said I. “What is the other problem?”

“We don’t think Marshall McLuhan is an appropriate outside advisor.”

“Why?”

“What would they think in the hinterlands, if they learned that Marshall McLuhan was advising a doctoral candidate in Canadian History?”

Without missing a beat, I stood up to announce that I was dropping out, effectively immediately, and leaving a lucrative scholarship behind me.

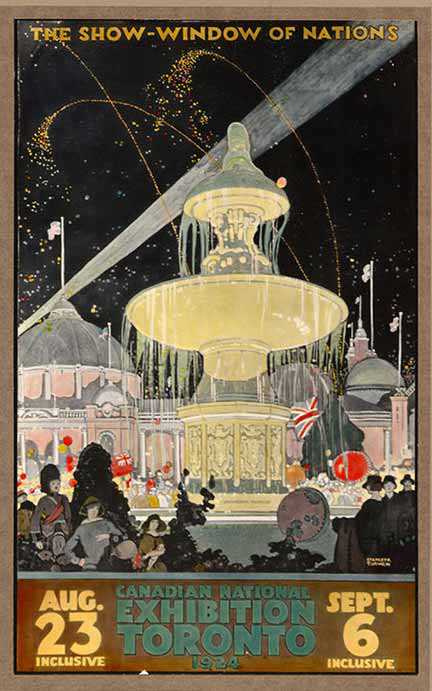

Once again, I walked across Queen’s Park. This time, my destination was the old Havergal College building at 354 Jarvis Street, which was then national headquarters for CBC English Radio. One of my undergraduate tutors was the Executive Producer of a show called Morningside. I stormed into her office without knocking. She asked me how I was doing. I told her that I’d just dropped out of a doctorate and was looking for a job. She said she couldn’t hire me, but sent me upstairs to a show called IDEAS.

The rest, as they say, is history.

That was the day my career in journalism started. Before leaving the building, I had a verbal contract to make an IDEAS documentary about the fur trade. A year later, I got an unsolicited call, asking me what I wanted to do next. After getting over my initial shock that they didn’t hate my debut documentary, I suggested a show about Innis. The immediate response was literally impossible to believe: How about five shows?

That’s when I decided I would be a journalist forever. It inspired my lifelong loyalty for IDEAS, which has been my home ever since. It’s also where Marshall McLuhan steps back into this story.

I dropped by the Centre for Culture and Technology to tell Marshall my good news – five hours, on IDEAS, about Harold Innis! I told him that I would obviously need to interview him for all five shows. He told me to contact his agent, Mrs. Molinari. The next day, she revealed that the fee would be $10,000. I felt embarrassed to confess that my fee – for the entire series! – was only slightly more than half that much.

“You people at the CBC are always short-changing Marshall. You don’t understand his value to the world.”

I desperately tried to explain that I was a mere freelancer with only a tenuous connection to the CBC. Nobody valued Marshall more than me, but Mrs. Molinari had all the power and she refused to budge. I threw myself into the project, assuming that it would never include McLuhan. The work proved to be both fascinating and fun. “Important” people agreed to give me interviews when they learned the results would be broadcast on IDEAS. Nobody turned me down.

On the night when the first show was broadcast, I was frantically cutting tape and writing script for the second episode, which was scheduled for the following week. A few minutes after 9 p.m. – which is when IDEAS signs off in Atlantic Canada – my phone rang.

“Hello, Paul … this is Marshall. I want to be in your program.”

“I want that, too! I really need you! But you sent me to Mrs. Molinari and she said I’d need to pay $10,000 …”

“Oh, don’t worry about her. She doesn’t understand these sorts of things. Just come around to the house on Sunday afternoon, and we’ll have another chat about Harold Innis.”

Careful listeners would have noticed that Marshall McLuhan appeared in all but the first episode of my five-part series about Innis, but nobody ever mentioned it to me. Nor has it caught the attention of any scholars or theorists who have written books or biographies about the media guru. Maybe that’s appropriate for somebody who considered himself to be no more than a footnote.

Marshall McLuhan saved me from an academic career that would have been way less interesting than the life I’ve had the privilege of living. This is not to suggest that he should be blamed (or praised) for jump-starting my media career. I don’t think he had any idea he was doing so. He was simply being the kind and generous human being that he couldn’t help but be, although you won’t find much about that in any of the biographies either.

I’m just grateful for this belated opportunity to say THANKS!

Who was McLuhan?

Herbert Marshall McLuhan (1911-80) was a media theorist, famously known for coining the term “the medium is the message.” Born in Edmonton, Alberta, McLuhan earned a PhD in literature from Cambridge in 1943. In 1946, McLuhan was hired as a professor of English by St. Michael’s College at the University of Toronto. McLuhan became known for his studies on the effects of mass media on human behaviour and in 1964, he published Understanding Media: The Extensions of Man, which brought him international attention. The ideas in Understanding Media were simplified into a pamphlet The Medium is the Massage (the title was published in error – it was supposed to read The Medium is the Message) and sold one million copies. McLuhan founded the University of Toronto’s Centre for Culture and Technology, a place for research and discussion and for the development of his ideas. His legacy lives on at the Centre, now known as the McLuhan Centre for Culture and Technology within the Faculty of Information.