Browse by category

- Adaptive reuse

- Archaeology

- Arts and creativity

- Black heritage

- Buildings and architecture

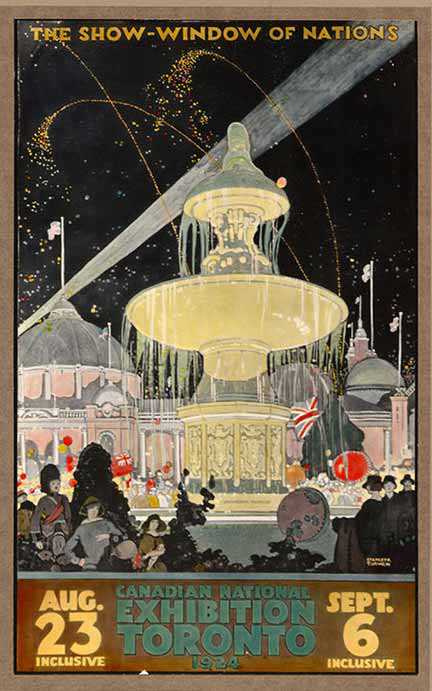

- Communication

- Community

- Cultural landscapes

- Cultural objects

- Design

- Economics of heritage

- Environment

- Expanding the narrative

- Food

- Francophone heritage

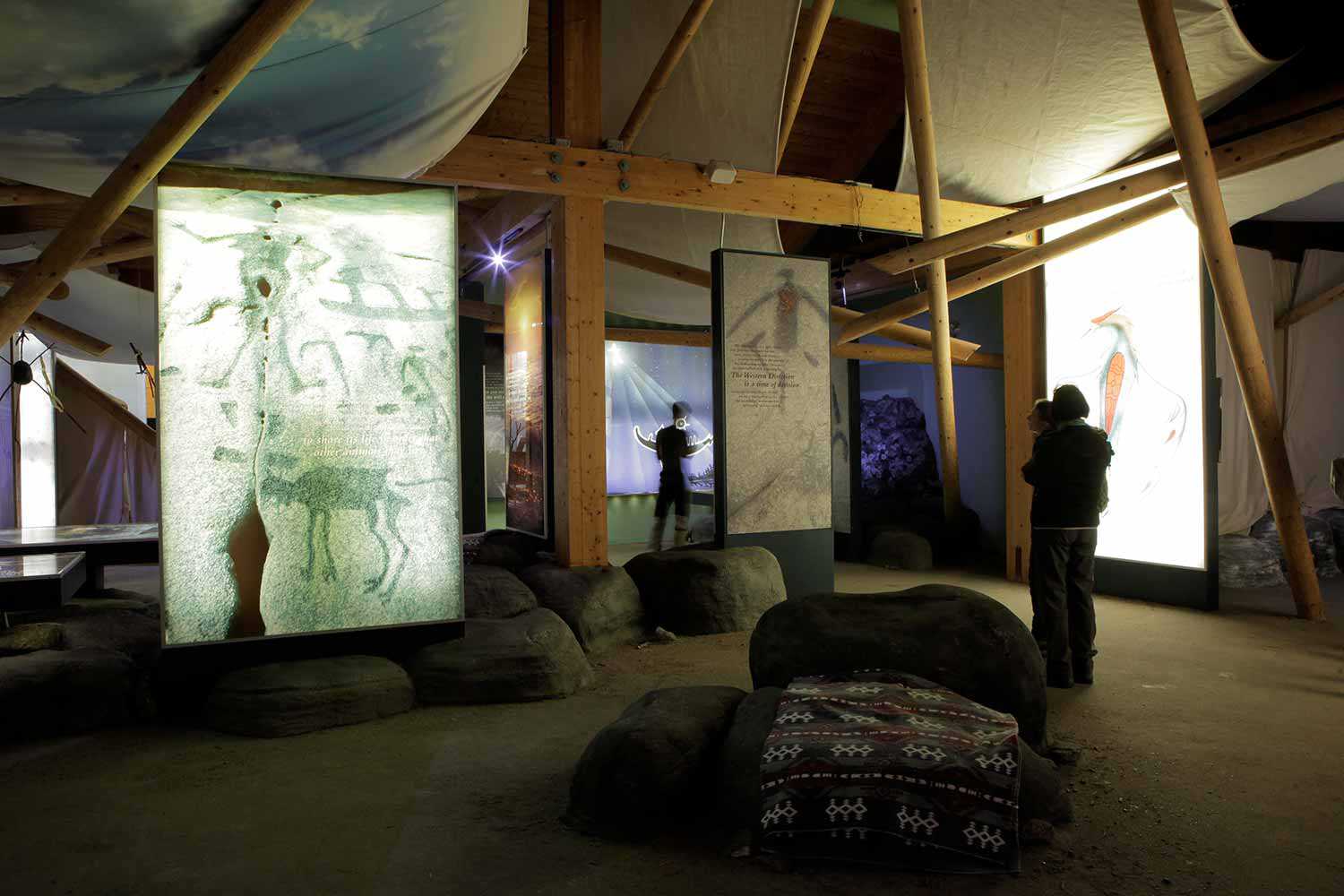

- Indigenous heritage

- Intangible heritage

- Medical heritage

- Military heritage

- MyOntario

- Natural heritage

- Sport heritage

- Tools for conservation

- Women's heritage

From the archives: The letters of Wellington and Mabel Ashbridge

As the Ontario Heritage Trust explores the theme of communication, we have been delving into our archival collections in search of letters that show how people in the past connected through the written word. Of course, letter writing was once the most popular form of longdistance communication. The Trust holds many letters written by the people associated with the heritage properties in our care. The courtship letters of Wellington Ashbridge (1869-1943) and his future bride Mabel Davis (1879-1952), from the archives of Toronto’s Ashbridge Estate , provide a fascinating glimpse into a romance between two ordinary people that developed across thousands of miles. Exchanged between 1902 and 1903, the letters reveal both the quirks and the surprising intimacy of this form of communication.

Wellington and Mabel’s correspondence began after they met at the Queen Street Methodist Church in their east-end Toronto neighbourhood. Shortly after, like many of his peers, Wellington was on a train westbound, a photo of Mabel tucked away in his trunk. He had taken up a temporary assignment as a civil engineer in Edmonton, while Mabel remained at her parents’ home in Toronto, commuting daily to her job at the downtown offices of the Toronto Railway Company.

Transcontinental telephone services would not become widely available in Canada until the 1920s, but regular postal service between the two bustling cities was well established following the expansion of the railway in the 1880s. Wellington and Mabel worked out a careful routine to ensure that each person knew when to expect their weekly letter. Still, lost letters were a common headache. “I am very sorry the letters have wound up in such a knot ...” wrote Wellington after one frustrating gap early in their correspondence, “… seems to me in fact I do nothing else but write but after I post them the responsibility gets on other shoulders and the railway does as it pleases.”

Over their year and a half correspondence, the evolving tone of the letters illustrates the conservative social conventions that guided communications between men and women in this period. For the first six months, there is no overt discussion of romance. Wellington and Mabel address one another strictly as “Miss Davis” and “Mr. Ashbridge.”

As the pair navigated daily struggles, the ritual of receiving a letter meant more than words alone – it was a physical token of affection and reassurance from a loved-one far away. Letter writing was time consuming, and both Wellington and Mabel repeatedly expressed appreciation for care that the other put into writing. “Such a nice Sunday letter you sent me,” wrote Mabel in April 1903. “I read it three times before night and then could hardly sleep thinking of it. The first thing I do when I open your letter is to count the pages and the more the better.”

To modern sensibilities, the idea of marrying someone who you haven’t spent significant time with in person is unthinkable, but Wellington and Mabel’s letters show that a successful long-distance correspondence in the early 20th century required patience and commitment – important personal qualities for a life partner.

Preserving cultural artifacts is part of the Trust’s integrated conservation strategy for protecting heritage places; our cultural collection consists of approximately 25,000 objects. Communication artifacts are part of a complex layering of history that also includes the architectural, archeological and natural features of our sites.

Other communication highlights from our collections include:

• Letters received by the Fulford family from Prime Minister William Lyon Mackenzie King, Lady Zoé Laurier and other historical figures (Fulford Place Museum)

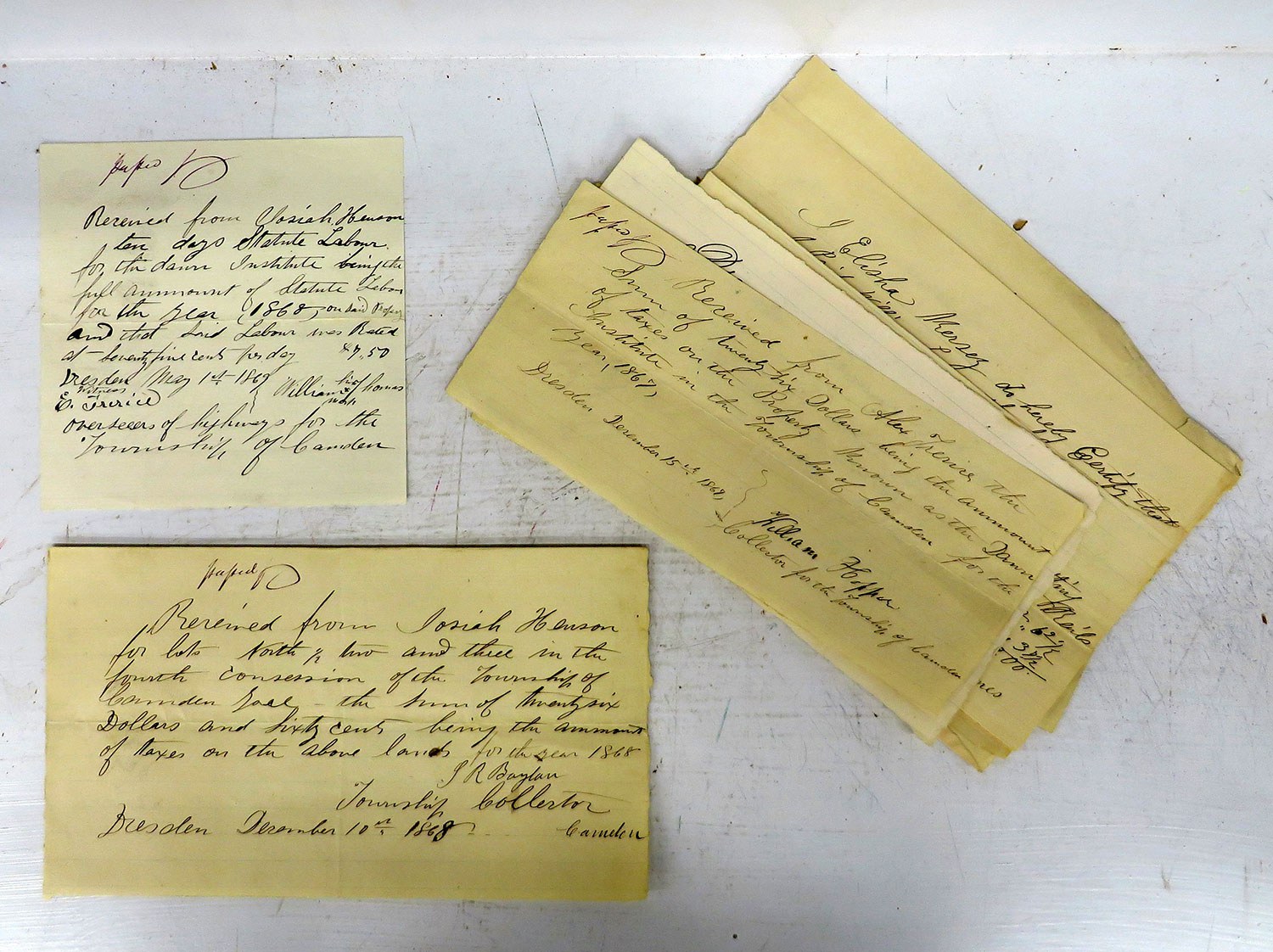

• Recently acquired documents related to the operation of the British American Institute, a school for refugees from slavery founded in 1842 by the abolitionist and Black community leader Josiah Henson (Uncle Tom’s Cabin Historic Site)

• A portable writing desk owned by the influential journalist and politician George Brown (George Brown House). The letters of George Brown are held by Library and Archives Canada and the Archives of Ontario.

Letters and other communication artifacts are an especially valuable resource for the Trust. We use them as a source of information during restoration projects, and they contain the human stories that give each property its unique character.