Browse by category

- Adaptive reuse

- Archaeology

- Arts and creativity

- Black heritage

- Buildings and architecture

- Communication

- Community

- Cultural landscapes

- Cultural objects

- Design

- Economics of heritage

- Environment

- Expanding the narrative

- Food

- Francophone heritage

- Indigenous heritage

- Intangible heritage

- Medical heritage

- Military heritage

- MyOntario

- Natural heritage

- Sport heritage

- Tools for conservation

- Women's heritage

Exploring Ontario’s southern peninsula

Buildings and architecture, Community

Published Date: Feb 11, 2010

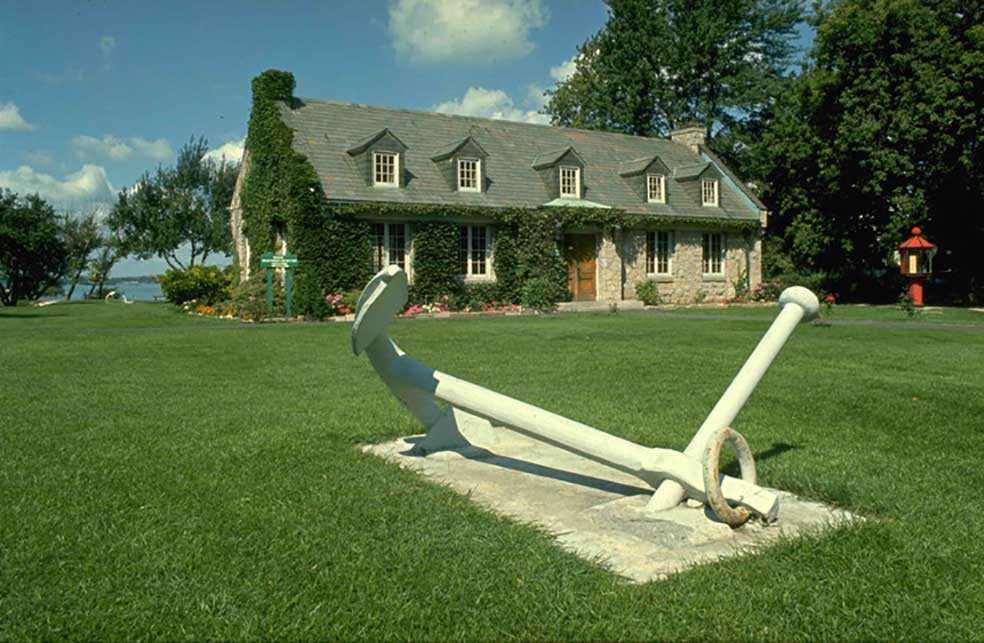

Photo: Fort Malden National Historic Site, Windsor (© Ontario Tourism 2010)

As you roam the highways and waterways of Ontario’s southern peninsula, a tapestry of stories unravels. These stories speak about settlement and growth, a testament to the people and events that helped shape this part of the province.

Starting above Lake Erie, the area is inextricably linked to the tobacco industry, as evidenced by the many tobacco sheds that dot the largely agricultural landscape. Aboriginal people were the first to cultivate tobacco for both spiritual and trade-related purposes. By the early 19th century, however, commercial cultivation of the plant was also being undertaken by area settlers. It was not until the First World War, however, that the industry began to prosper in southwestern Ontario. By the mid-1920s, large amounts of land were converted to prosperous tobacco farms, particularly in the area around Tillsonburg and Delhi. The Ontario Tobacco Museum and Heritage Centre in Delhi preserves the history of the province’s tobacco industry – an industry that has declined in recent years, forcing area farmers to diversify their crops and seek creative and challenging alternatives to maintain their livelihood.

Travelling northwest, one reaches the town of Ingersoll – another community rich in agricultural heritage. A visit to the Cheese and Agricultural Museum provides a window into the development of the area’s dairy industry. The “Big Cheese of 1866” – produced at the James Harris Cheese Company – weighed a staggering 7,300 pounds. This wheel of cheese raised the profile of Canadian cheddar as a trade commodity while it was on display in London, England.

Southwest of Ingersoll sits Ontario’s own city of London. Located at the “Forks of the Thames,” the site was selected as an ideal location for the capital of Upper Canada by Lieutenant Governor John Graves Simcoe in 1793, but plans to establish the capital there were abandoned when Simcoe left Upper Canada in 1796.

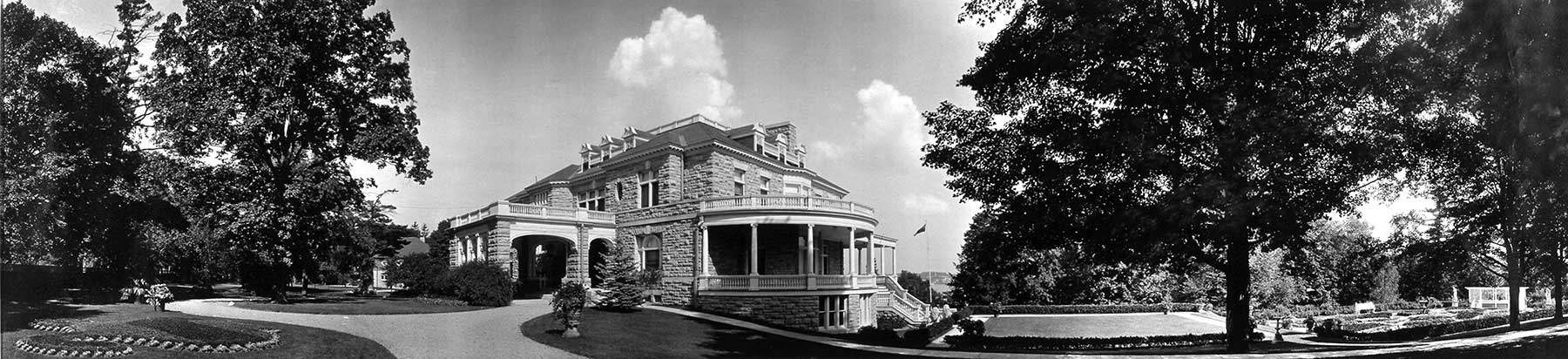

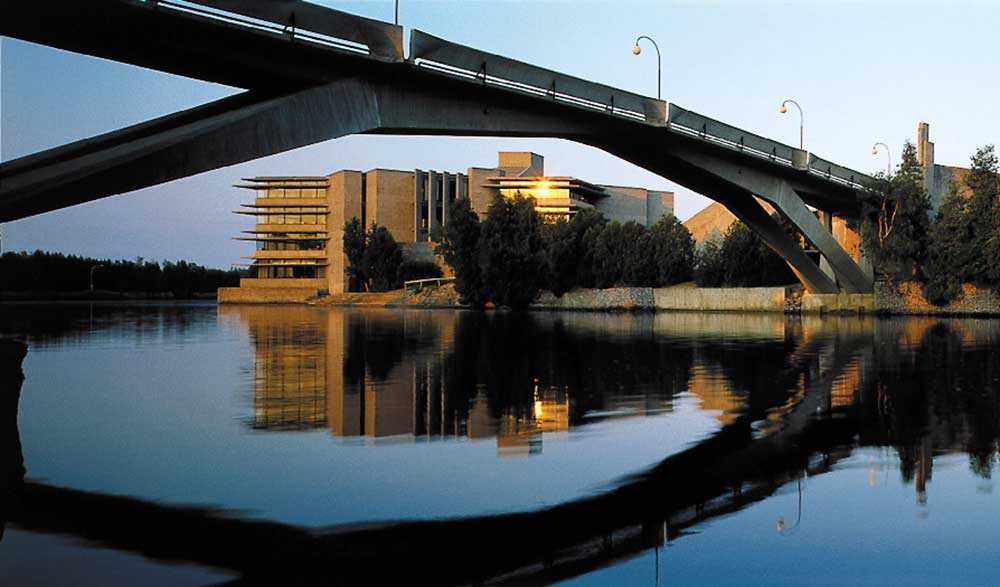

In 1826, London was established as the new district town, and officials of the London District gradually began to move to the new centre from their well-appointed homes in Norfolk County. By 1860, London was a successful administrative and commercial centre. Today, its metropolitan population exceeds 400,000. The Forks of the Thames now consists of an interconnected series of parks within walking distance of many of the city’s built heritage attractions – including Eldon House, London’s oldest remaining residence.

In 2000, the Thames River – which runs through London and passes through several communities, including Chatham, before emptying into Lake St. Clair – was designated a Canadian Heritage River. Historically, it served as an access route for settlement; numerous saw and grist mills were established along its banks. Today, the river is home to one of Canada’s most diverse fish communities, providing habitats for 88 species. The watershed represents a tangible intersection of cultural and natural heritage in southwestern Ontario.

Some 30 kilometres south of London sits St. Thomas, a community that celebrates its railway heritage. In 1856, the London and Port Stanley Railway commenced operations running south from London to St. Thomas and then on to Port Stanley on the shore of Lake Erie. The decision to route the line via St. Thomas had a significant impact on the growth and development of that community’s railway industry. By 1914, there were eight railways operating in St. Thomas and over 100 trains passed through the community daily. The industry remained the dominant employer in St. Thomas until the 1950s.

St. Thomas is also an excellent place to discover the impact of Colonel Thomas Talbot on the growth and development of this region of the province. A chief colonizer of Ontario’s southern peninsula, he had established thousands of settlers on his land holdings by 1828. He also supervised construction of a 483-kilometre/300-mile road along much of Lake Erie’s north shore.

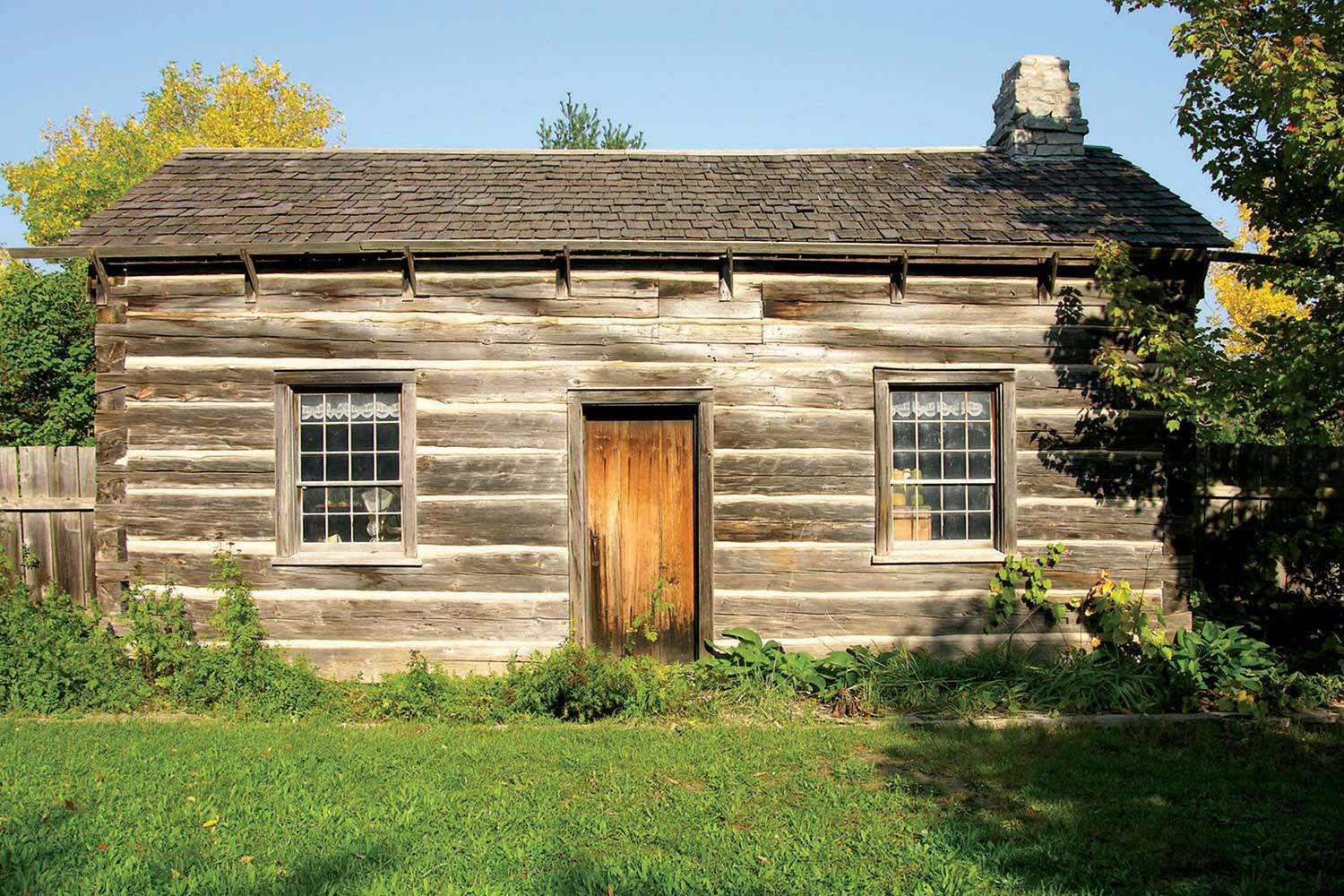

South of St. Thomas at Sparta, an Ontario Heritage Trust provincial plaque commemorates the “Sparta Settlement,” a Quaker community founded in 1815 on a 3,000-acre/1,214-hectare land grant obtained by Jonathan Doan. By 1821, the settlement was a thriving agricultural centre.

Farther south is the lakeside community of Port Stanley. While it has been a working fishing village for over a century, Port Stanley also became an important tourist attraction in the early 1900s with its sandy beaches, casino and big band venue – the Stork Club. Today, many tangible reminders of Port Stanley’s identity exist throughout the community; it is still an important summer tourist destination. As a reminder of the area’s railway heritage, Port Stanley Terminal Rail continues to operate tourist excursion trains along portions of the former London and Port Stanley Railway line.

Heading west, beautiful Rondeau Park waits to be explored. Located approximately 85 kilometres/53 miles west of Port Stanley along the Talbot Line/Trail, Rondeau Park is Ontario’s second oldest provincial park and protects an important and rare Carolinian habitat. Similarly, farther west, Point Pelee and Pelee Island offer striking bird-watching opportunities. Created in 1918, Point Pelee National Park encompasses 20 square kilometers/7.7 square miles of varied landscape, including: marshes, Carolinian forest, Savannah grasslands, and, of course, the Point itself – a 10-kilometre/6.2-mile sand spit jutting out into Lake Erie. Pelee Island forms the southernmost portion of Canada and is also noted for grape growing and recreational fishing opportunities.

The name Pelee speaks to the area’s cultural heritage and is derived from the French usage, “pointe pelée,” meaning “bald point.” The peninsula was aptly named by French explorers who followed the Aboriginal “carrying place” route through the marsh to avoid the dangerous currents at the peninsula’s tip.

Northwest of Point Pelee is the self-proclaimed tomato capital of Canada, Leamington. In 1899, in an attempt to attract new industry, Leamington’s town council passed a bylaw that enticed manufacturers to relocate to this community. This decision paid off when, in 1908, H.J. Heinz Company of Canada chose to establish its operations at Leamington. In 1910, the company produced its first bottle of ketchup and the community’s identity has been linked to tomatoes ever since.

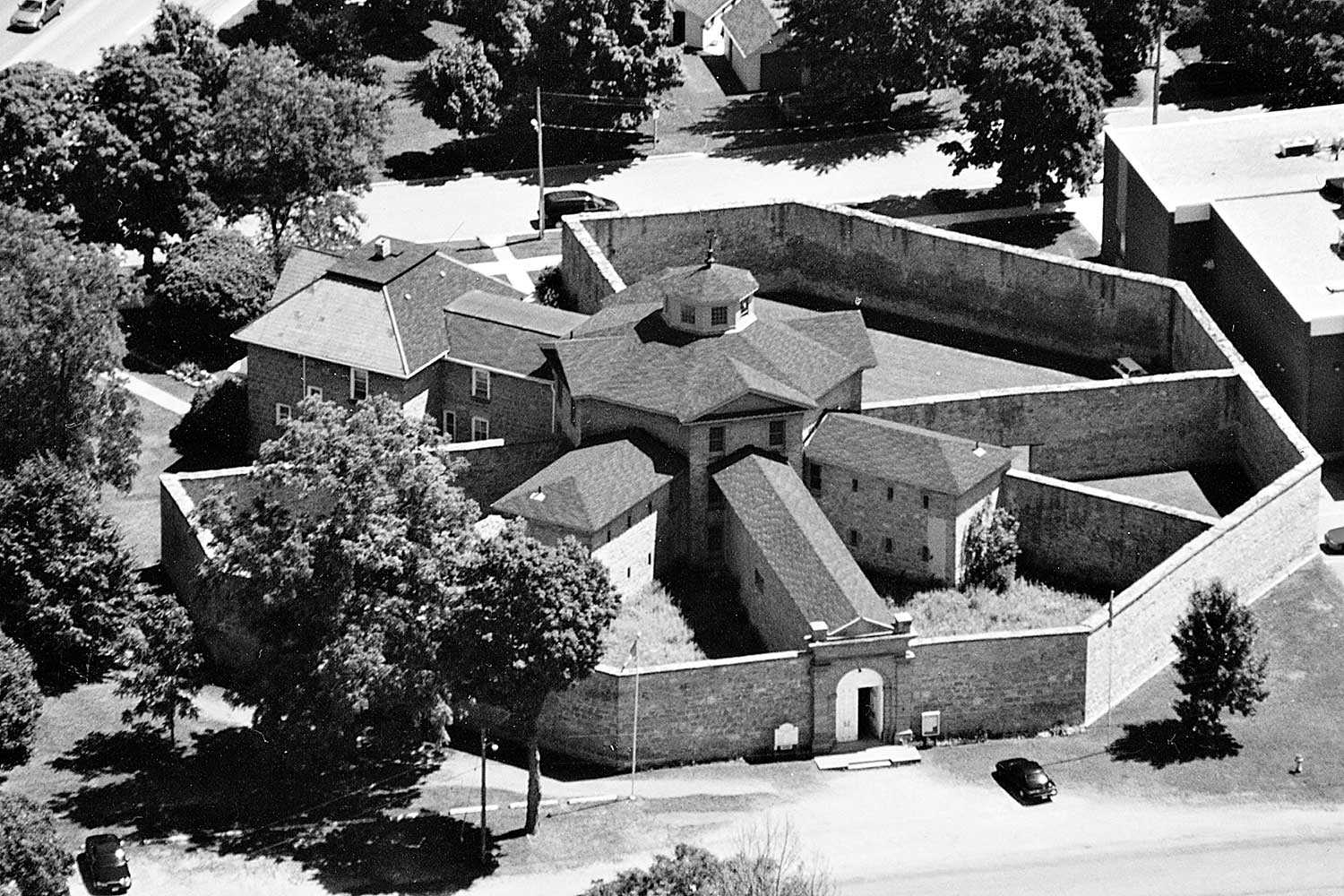

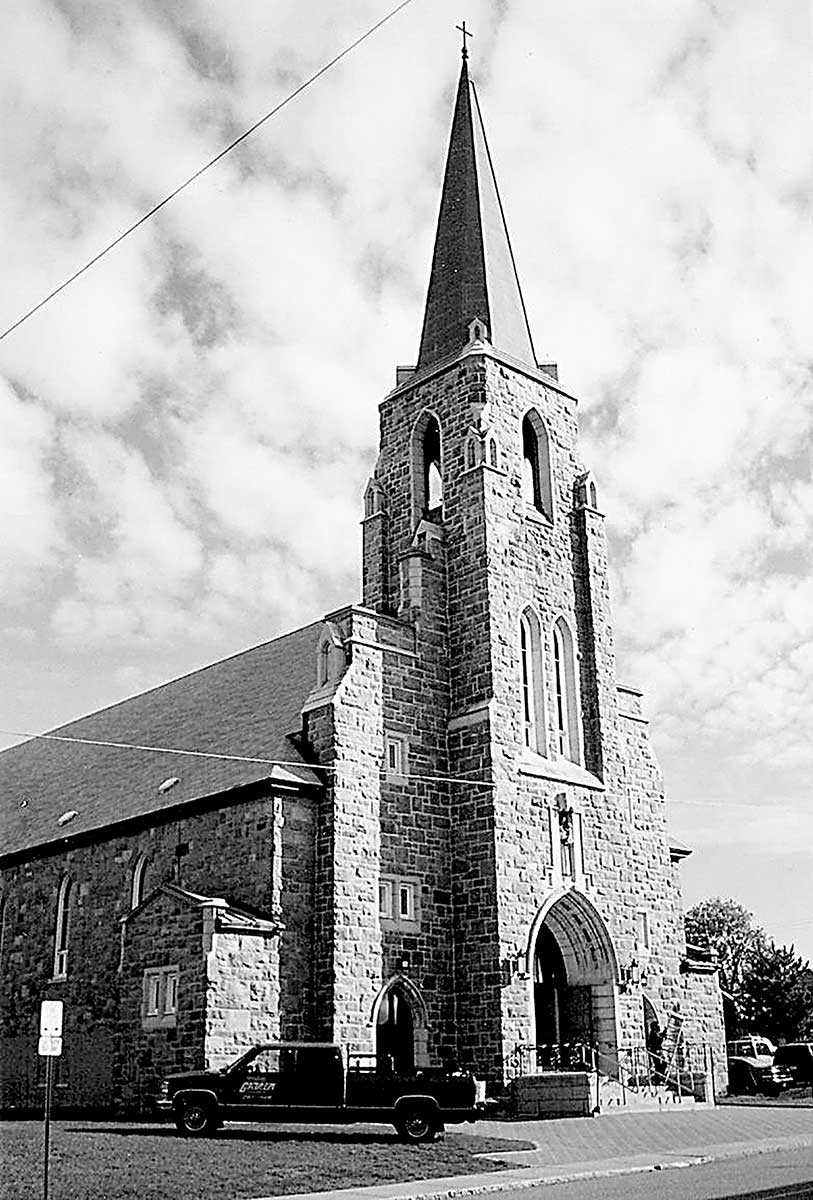

Travelling west from Leamington to the edge of the peninsula at Amherstburg, one learns more about Upper Canada’s military heritage through a visit to Fort Malden National Historic Site. The site’s first post, Fort Amherstburg, was constructed in 1796 and served as the regional headquarters for British forces during the War of 1812. It was destroyed by the British when they were forced to retreat in 1813. Fort Malden was constructed after the War of 1812 and rebuilt in 1838-40 when it served as a centre for British defence during the Upper Canada Rebellion of 1837-39.

Amherstburg is also home to the North American Black Historical Museum and Cultural Centre. It offers visitors a chance to learn more about the Underground Railroad and the experiences of Black freedom seekers who escaped from slavery in the United States to settle in this part of Ontario. It is one of many sites in the area that preserve and promote an understanding of the province’s unique Black heritage.

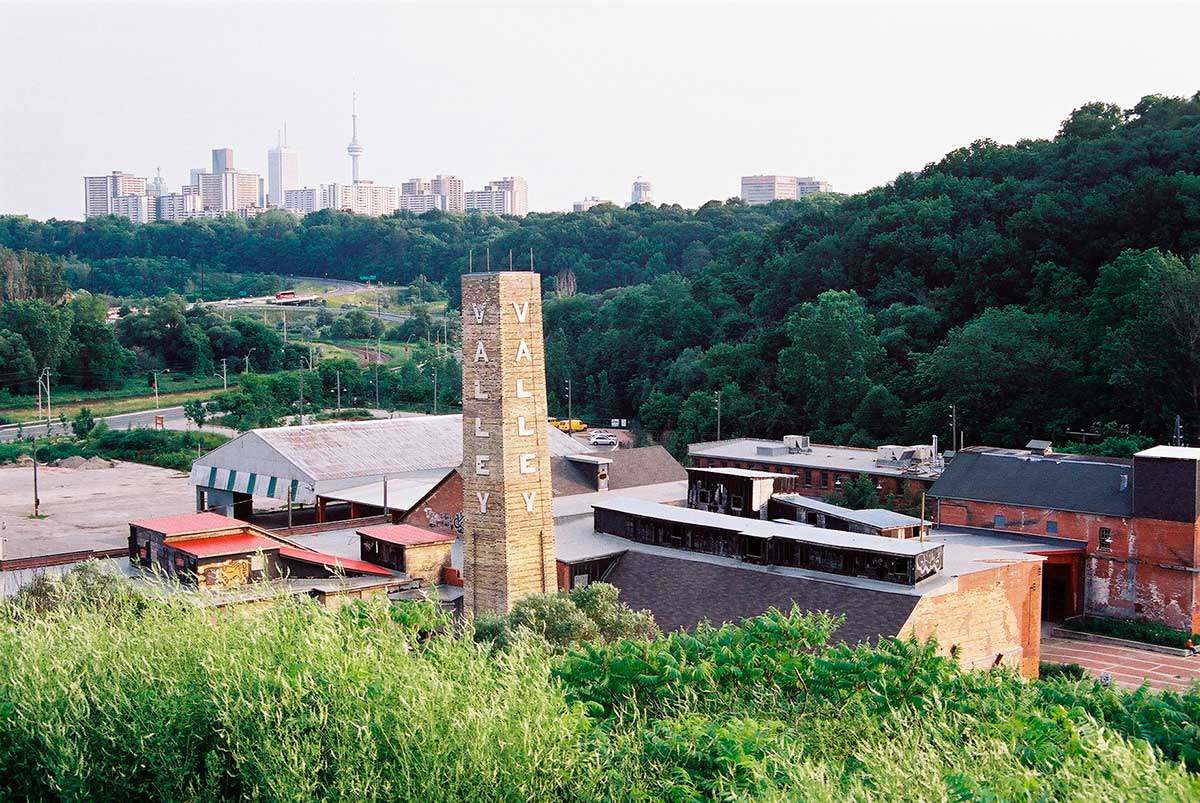

Following the Detroit River north from Amherstburg around the edge of the peninsula leads to Windsor – a city with significant cultural and industrial heritage narratives. Known as the oldest identified site of continued settlement in Ontario, Windsor has a dynamic French heritage that dates back to the 18th century and continues to be reflected in the patterns and names of its streets.

In the mid-18th century, the government of New France had realized the strategic importance of an increased presence on the Detroit River. In 1749, it offered land for agricultural settlement on the river’s south shore. Together with civilians and discharged soldiers from Fort Pontchartrain (Detroit), families who had relocated from the lower St. Lawrence River formed the settlement of La Petite Côte. When the French régime ended in 1760, close to 300 settlers were living in the community.

Windsor is also a city with a fascinating industrial heritage that continues to inform its past, present and future. In 1854, the Great Western Railway selected Windsor as its terminus. This decision marked the beginning of much of Windsor’s industrial development, including Hiram Walker’s decision to establish his distillery in 1857 at a site just east of downtown (Walkerville) where the Great Western Railway first met the waterfront.

Much of Windsor’s 20th-century industrial heritage is linked to the automobile industry. During and after the First World War, an area known as “Ford City” grew up around the company’s industrial complex. A walking tour of Ford City developed by the Windsor Architectural Conservation Advisory Committee provides an excellent glimpse into Windsor’s industrial heritage, which continues to impact this riverside city.

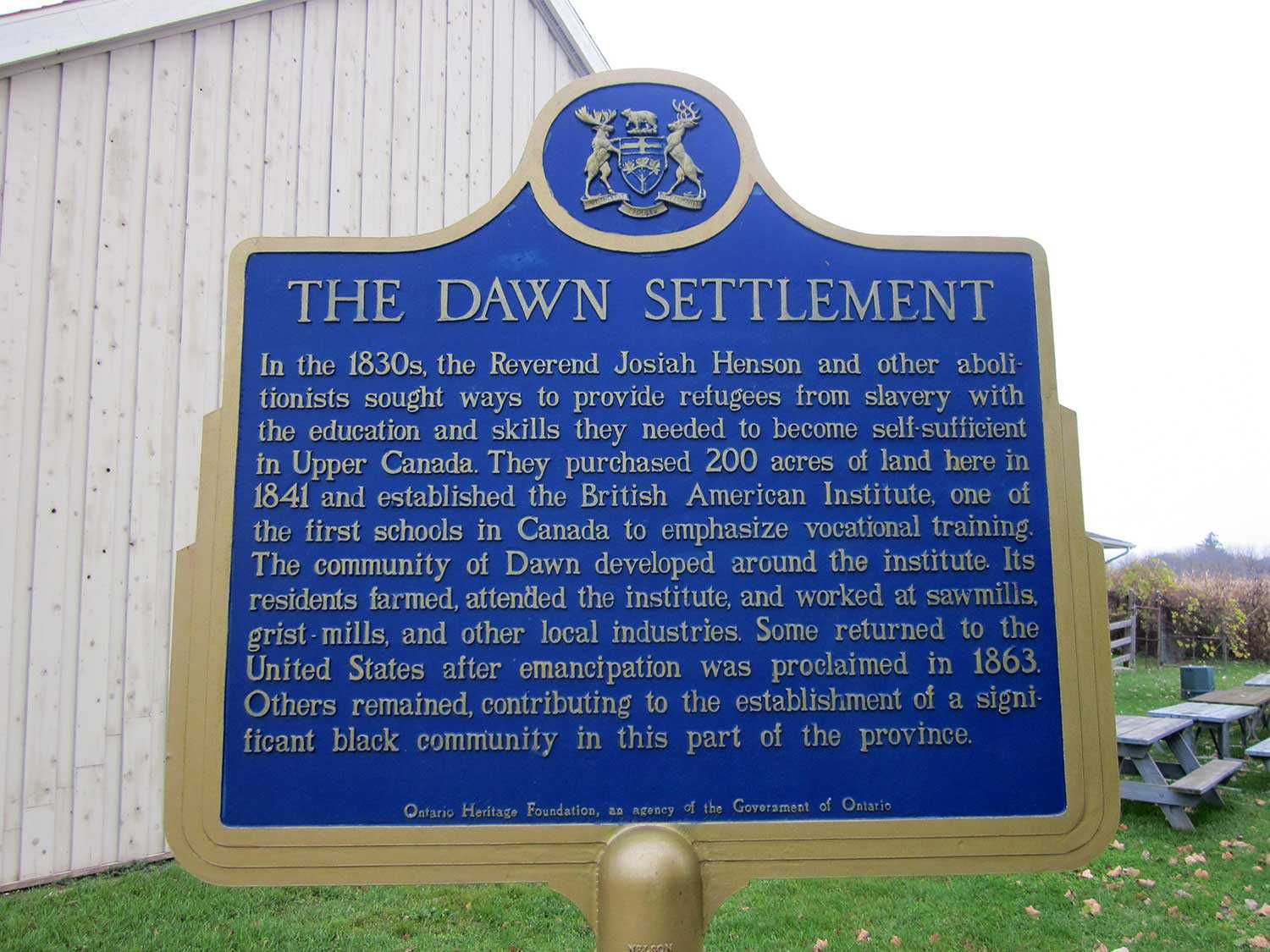

As one heads east from Windsor towards Chatham, a number of sites tell the story of Ontario’s Black heritage. Buxton National Historic Site and Museum in North Buxton tells the story of the Elgin Settlement, founded in 1849 by William King, as a place where fugitive slaves and free Blacks fleeing oppression in the United States could begin anew in Canada. Farther north, the First Baptist Church at Chatham and Uncle Tom’s Cabin Historic Site (owned and operated by the Ontario Heritage Trust) at Dresden continue the complex story of Ontario’s Black heritage.

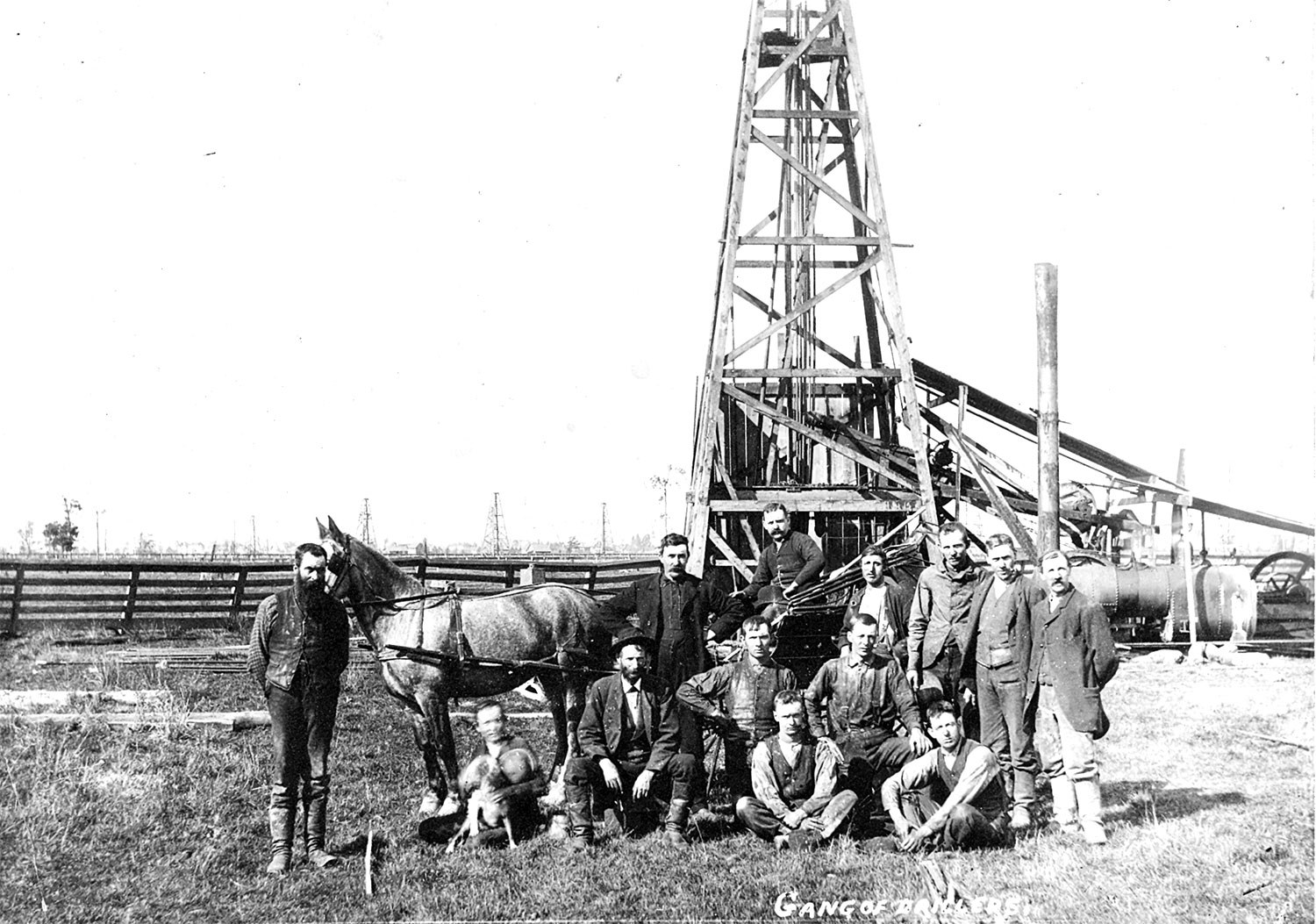

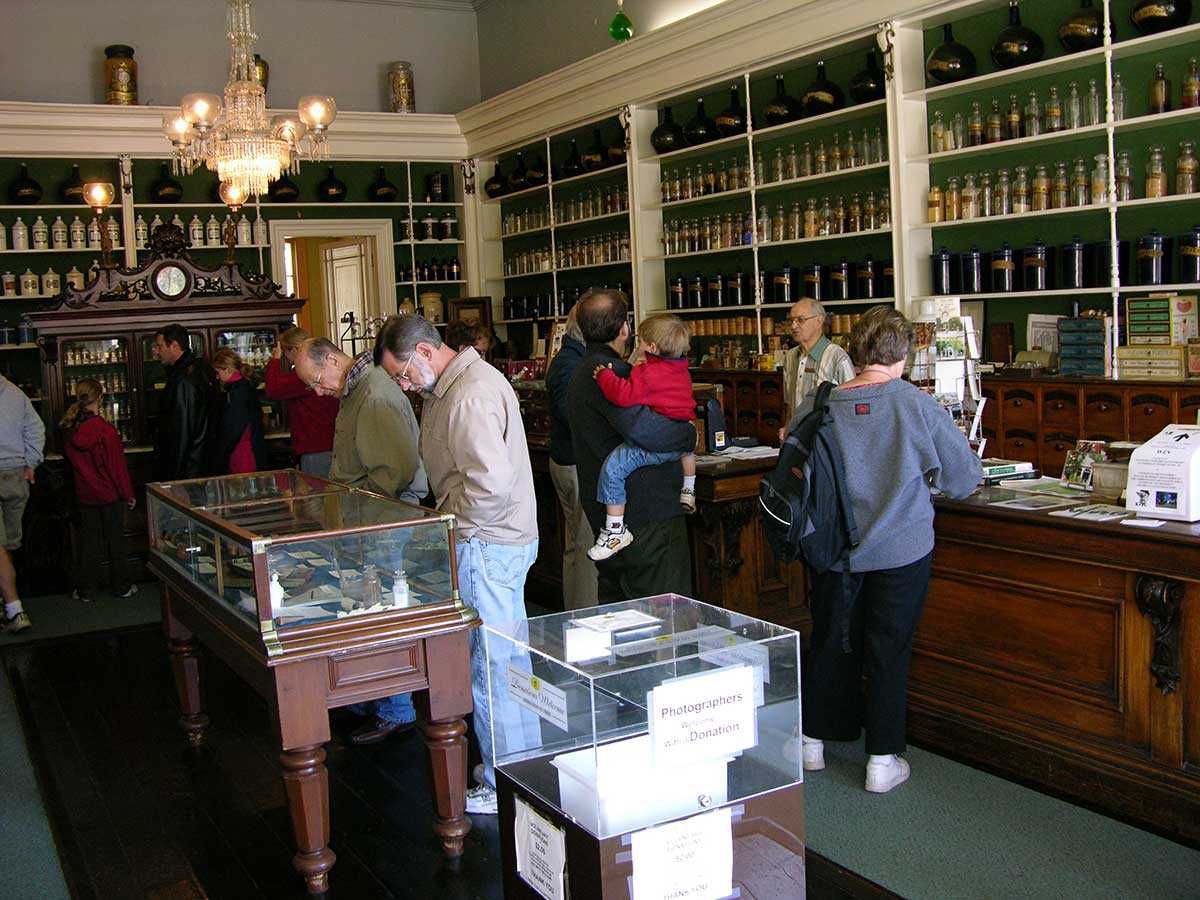

East of Dresden on the St. Clair River, the Walpole Island First Nation works actively to preserve its cultural heritage and traditional knowledge. Northeast of Walpole Island, opportunities abound to explore Ontario’s oil producing heritage. The communities of Oil Springs, Petrolia and Sarnia all play a part in the province’s oil heritage narrative. A visit to the Oil Museum of Canada in Oil Springs, which preserves the site of North America’s first commercial oil well dug by James Miller Williams in 1858, is an excellent place to begin a tour of Ontario’s Oil Heritage District.

The heritage narratives of Ontario’s southern peninsula combine to produce a rich and diverse fabric of cultural and natural heritage. By engaging with this heritage, we see how the past has informed the growth and development of this part of Ontario, and will continue to do so in the future.

![J.E. Sampson. Archives of Ontario War Poster Collection [between 1914 and 1918]. (Archives of Ontario, C 233-2-1-0-296).](https://www.heritage-matters.ca/uploads/Articles/Victory-Bonds-cover-image-AO-web.jpg)