Browse by category

- Adaptive reuse

- Archaeology

- Arts and creativity

- Black heritage

- Buildings and architecture

- Communication

- Community

- Cultural landscapes

- Cultural objects

- Design

- Economics of heritage

- Environment

- Expanding the narrative

- Food

- Francophone heritage

- Indigenous heritage

- Intangible heritage

- Medical heritage

- Military heritage

- MyOntario

- Natural heritage

- Sport heritage

- Tools for conservation

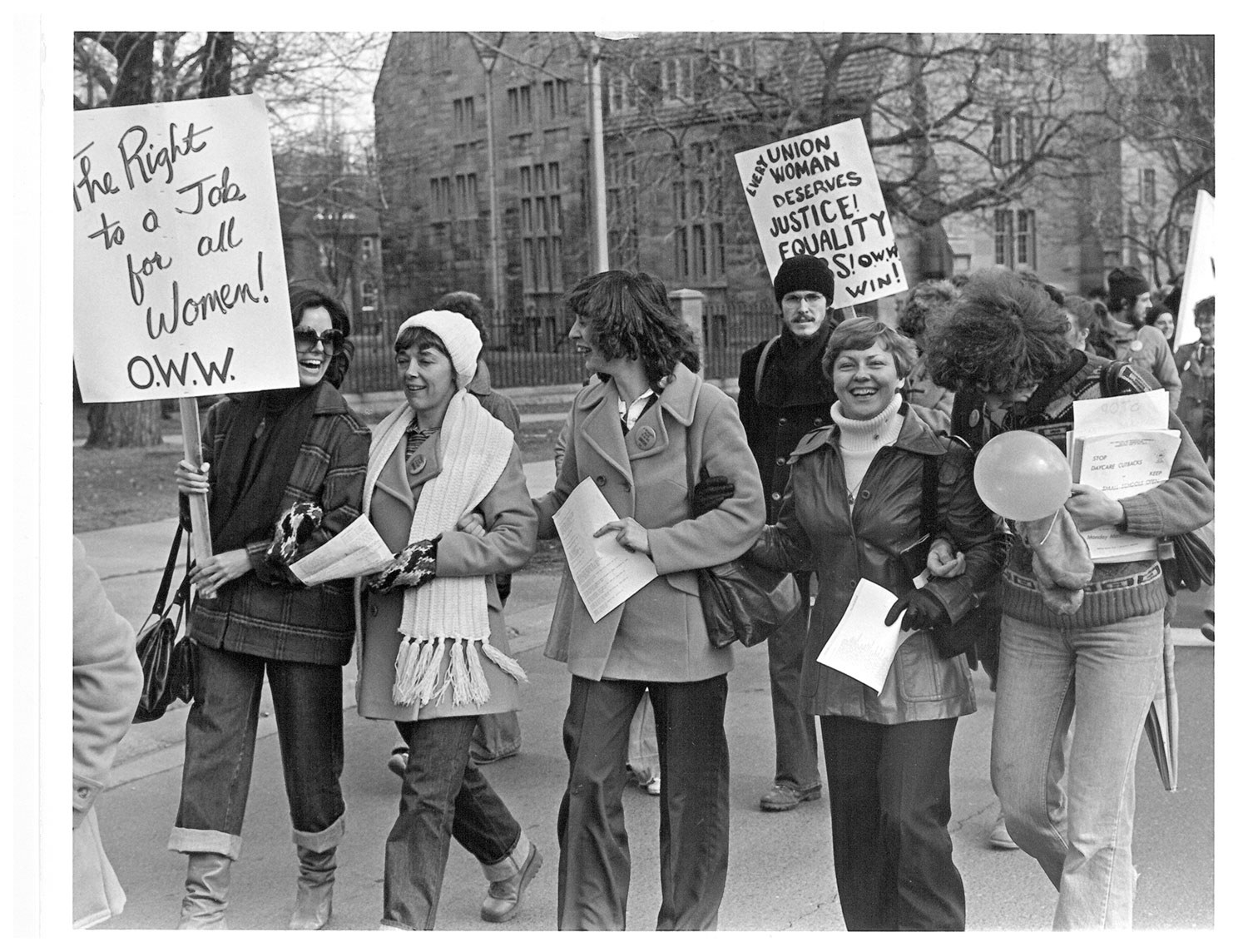

- Women's heritage

Elizabeth Bagshaw: Fighting for reproductive rights in Canada

Women's heritage, Medical heritage

Published Date: Mar 20, 2018

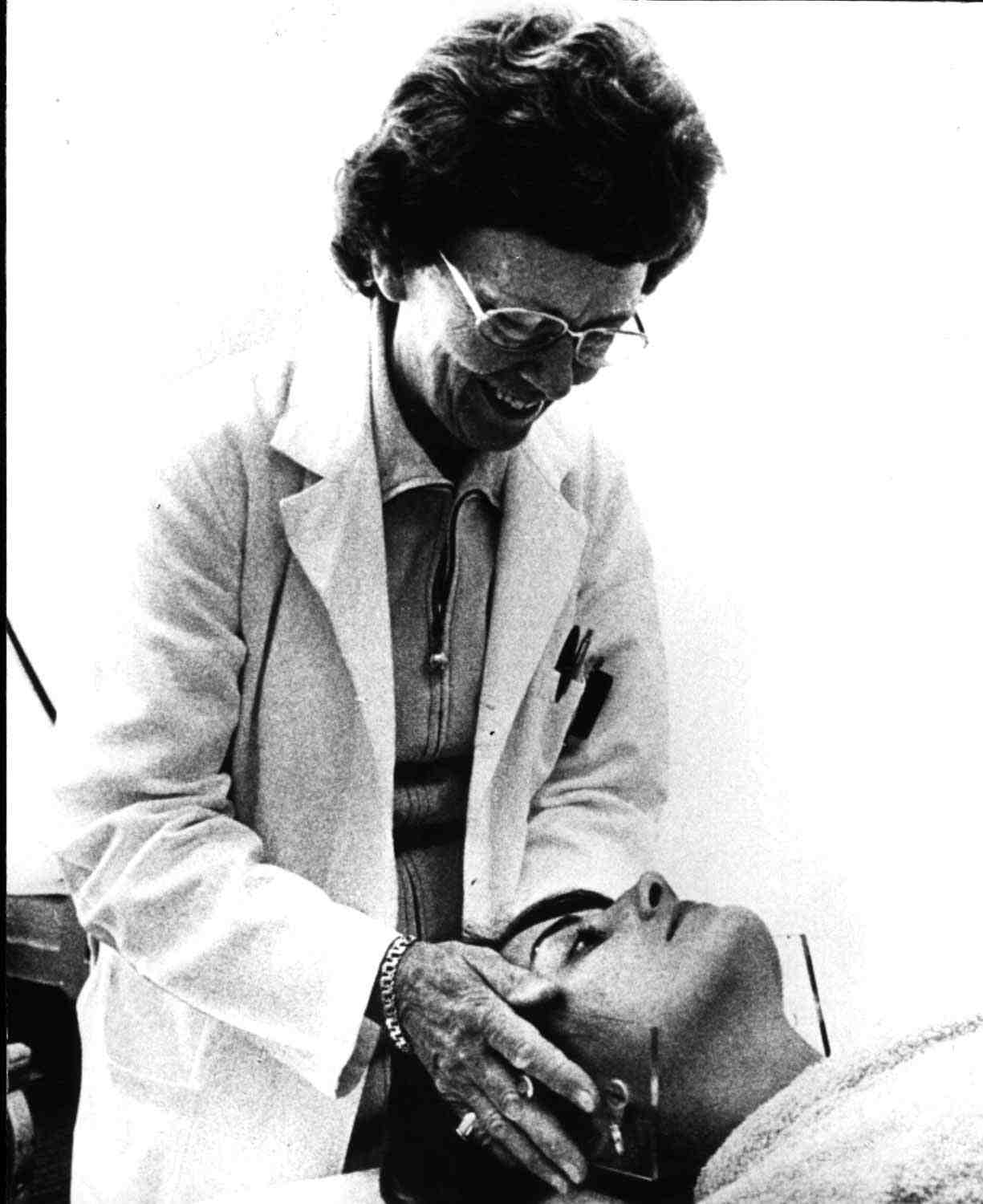

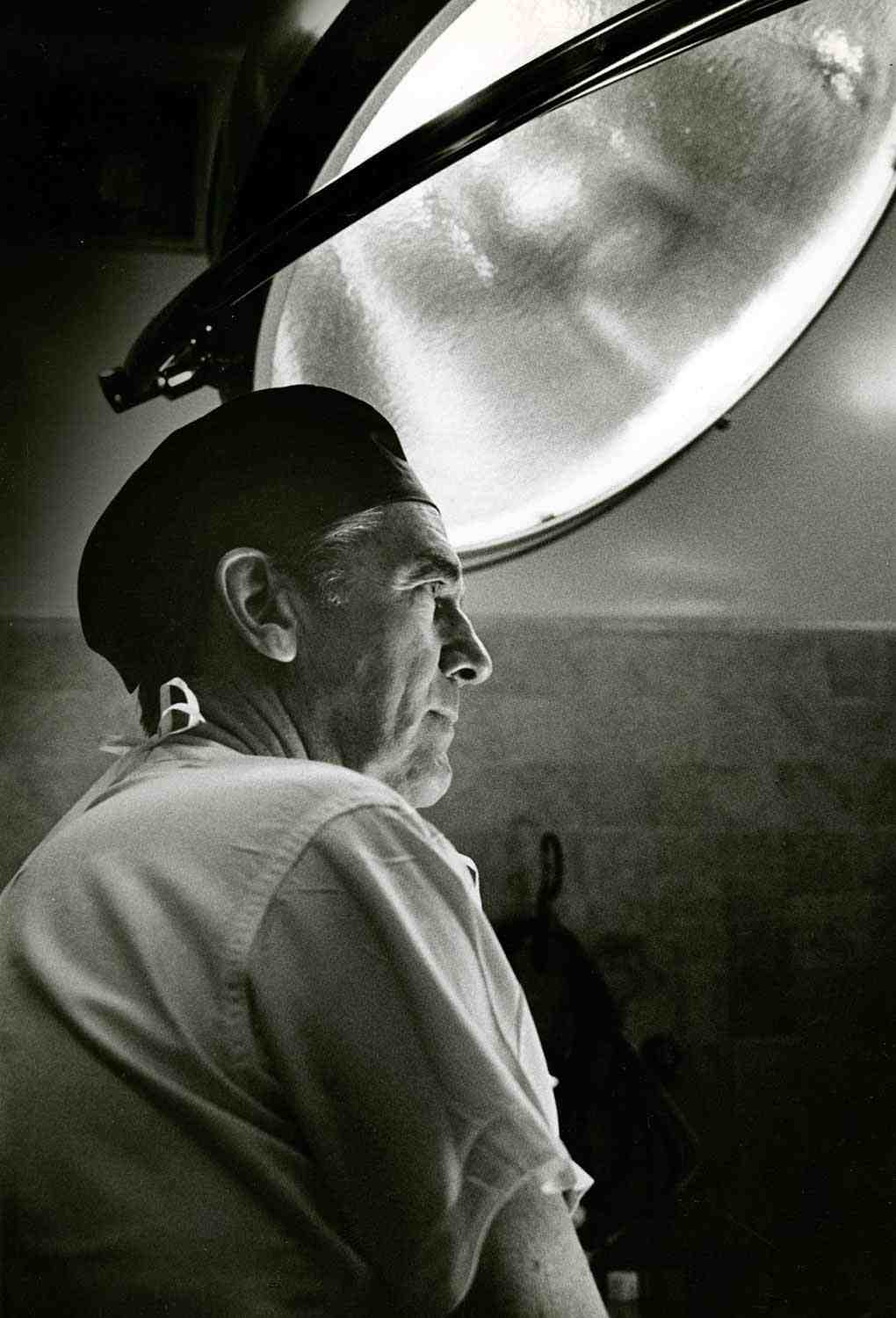

Photo: Elizabeth Bagshaw (Photo courtesy of The Hamilton Spectator)

When Dr. Elizabeth Bagshaw retired in 1976, she was the oldest physician practising in Canada. In her illustrious 70-year career, Bagshaw treated thousands of patients and delivered more than 3,000 babies. She was the recipient of a number of accolades, including the Order of Canada, the Governor General’s Persons Award, Hamilton’s Person of the Year, inductee of the Medical Hall of Fame, and subject of a 1978 National Film Board documentary. But Bagshaw was arguably best known as a champion for women’s reproductive rights at a time when advocating for and providing any type of contraception was illegal.

In 1905, Bagshaw graduated medical school from the Ontario Medical College for Women, affiliated with the University of Toronto, defying the wishes of her mother (but with the support of her father). She was one of the first female doctors in Canada and faced barriers in her education and starting her career. Many of her classes were segregated by gender and she had difficulties securing the hospital internship necessary to obtain her license to practise medicine, as there were few internships in Canada open to women at that time.

Eventually, Bagshaw was able to find a preceptorship (an alternative to an internship) working under another female doctor. By 1906, she was able to set up her own practice in Hamilton, specializing in family medicine and obstetrics. The practice was successful; during a three-year period in the 1920s, she signed more birth certificates than any other Hamilton physician. Bagshaw remained single, but adopted the child of a relative when she was in her 40s. Bagshaw’s biographer, Marjorie Wild, remarked that, “She was making her own choices, acting on her own decisions, at a time when most women were still looking to men for the major decisions of life.”

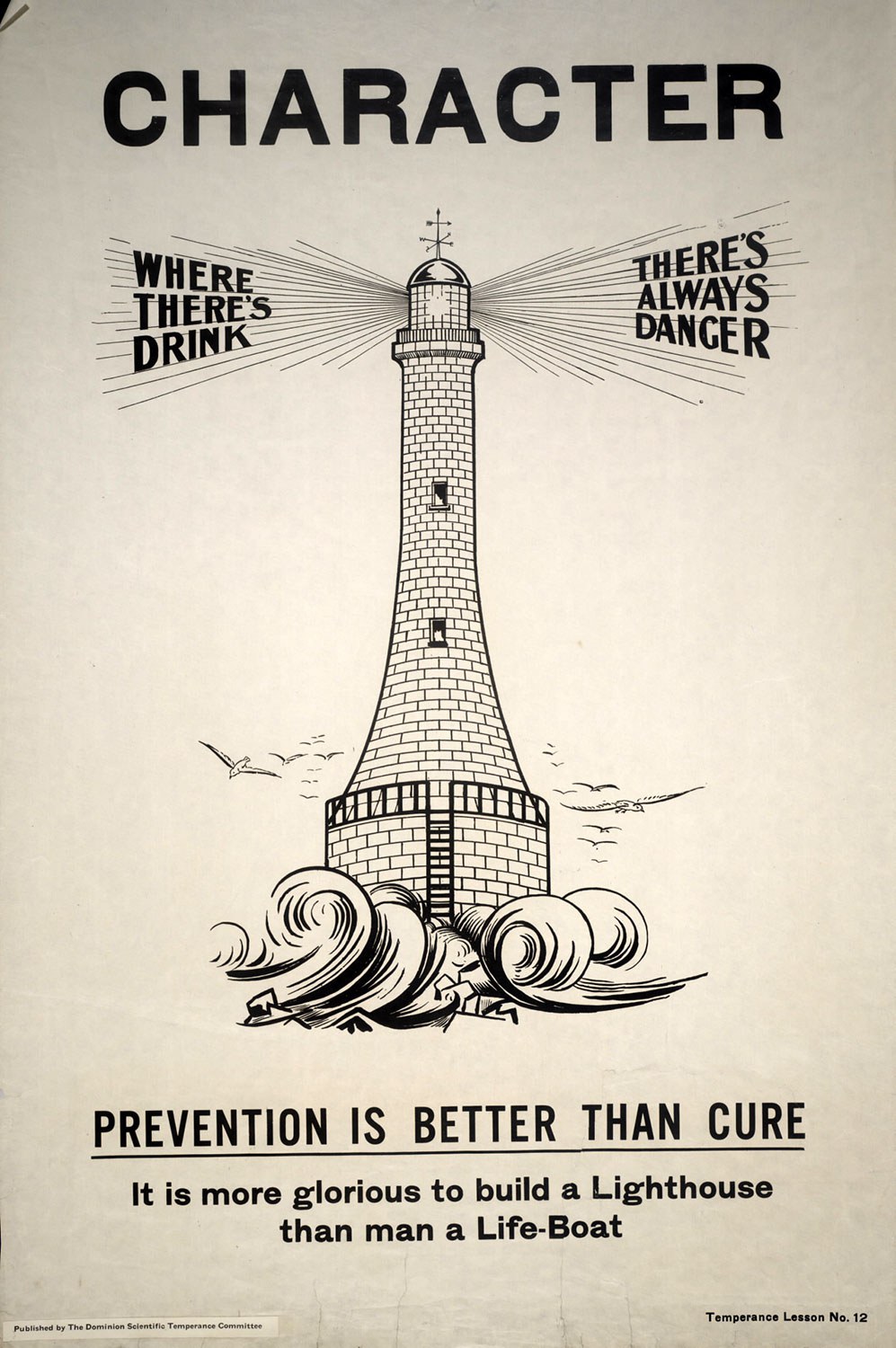

Bagshaw was also practising medicine at a time when women had few reproductive rights. There was no legal access to abortion or contraception. There was an 1892 federal law that made it illegal to provide access to, or even disseminate information about, birth control – and those who were convicted faced up to two years imprisonment. But, as a frontline physician, Bagshaw saw the impact of pregnancy and childbirth on women. A 1934 study showed that one in six deaths among young women in Ontario was the direct result of pregnancy and childbirth. Illegal abortions also contributed to maternal death rates. Between 1926 and 1947, an estimated 4,000 to 6,000 women in Canada died as a result of abortions – a number that was likely underreported given the social stigma around the procedure. In the 1930s, Ontario’s Division of Maternal and Child Hygiene revealed that abortion consistently accounted for 20 per cent of all maternal deaths in Ontario.

As the Great Depression hit, Bagshaw could see the impact on her patients. She recounted that “the Depression came on and we had a lot of poor people. There was no welfare and no unemployment payments, and these people were just about half-starved because there was no work. They couldn’t afford to have children if they couldn’t afford to eat.” In 1932, Bagshaw signed on as medical director of Canada’s first birth control clinic. The clinic was illegal and could not operate publicly. The first year the clinic was open, they expected 60 people. Instead, more than 400 arrived.

Bagshaw and her colleagues faced criticism from medical and religious communities. Local bishops advised women to avoid the clinic. “They called me a devil,” Bagshaw remarked years later. “I didn’t worry about it.” She served as medical director of the clinic for more than 30 years, stepping down in 1967. When birth control was finally decriminalized two years later, the clinic could operate openly for the first time.

Dr. Elizabeth Bagshaw is just one of the contributors to the long struggle for women’s reproductive rights throughout the 20th century, including the Morgentaler decision that led to the legalizing of abortion in 1988. This is a fight that continues today. Although access to birth control and abortion is enshrined legally, the issue for Canadian women today is one of access to safe sexual and reproductive health care. Those outside of major cities travel long distances, face delays and incur significant costs to access necessary care. Advocates today, building on the legacy of Bagshaw and her contemporaries, are focused not only on preserving legal rights, but on these aspects of reproductive justice to ensure that women in Canada have equality of access to reproductive health care.

![“Mayor Oliver: Wonder who told them we didn’t encourage the suffragette movement in Toronto?”, [photograph], ca. 1910, Newton McConnell fonds, C 301-0-0-0-996, Archives of Ontario.](https://www.heritage-matters.ca/uploads/Articles/Archives-of-Ontario-cartoon-I0007312-web.jpg)

![F 2076-16-3-2/Unidentified woman and her son, [ca. 1900], Alvin D. McCurdy fonds, Archives of Ontario, I0027790.](https://www.heritage-matters.ca/uploads/Articles/27790_boy_and_woman_520-web.jpg)

![Wyland, Francie. 1976. Motherhood, Lesbianism, Child Custody: The Case for Wages for Housework. Toronto: Wages Due Lesbians. Cover woodcut by Anne Quigley. CLGA collection, in monographs, folder M 1985-054].](https://www.heritage-matters.ca/uploads/Articles/Wages-Due-Lesbians_Wyland-pamphlet-image-web.jpg)