Browse by category

- Adaptive reuse

- Archaeology

- Arts and creativity

- Black heritage

- Buildings and architecture

- Communication

- Community

- Cultural landscapes

- Cultural objects

- Design

- Economics of heritage

- Environment

- Expanding the narrative

- Food

- Francophone heritage

- Indigenous heritage

- Intangible heritage

- Medical heritage

- Military heritage

- MyOntario

- Natural heritage

- Sport heritage

- Tools for conservation

- Women's heritage

Developing communities: French-Canadian settlement in Ontario

Francophone heritage

Published Date: May 18, 2012

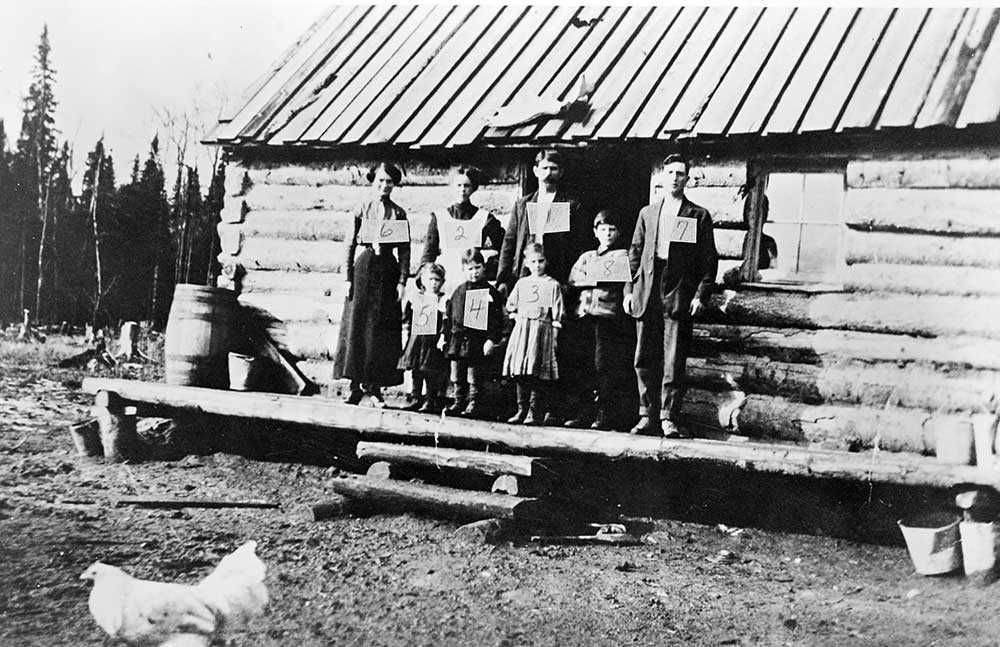

Photo: The family of Simon Aumont. Only Simon himself and Irène (seated, holding a doll), survived the great fire that devastated the region in 1916, Val Gagné (Ontario), [before 1916]. University of Ottawa Centre for Research on French Canadian Culture, TVOntario archive (C21), reproduced from the collection of Germaine Robert, Val Gagné, Ontario.

In 1840, as Upper Canada was about to become Canada West, a grand migratory movement began from the neighbouring colony of Canada East (Quebec). The francophone enclaves in Essex, Georgian Bay and the Bytown (Ottawa) region were strengthened, and new areas were opened up to settlement by French Canadians.

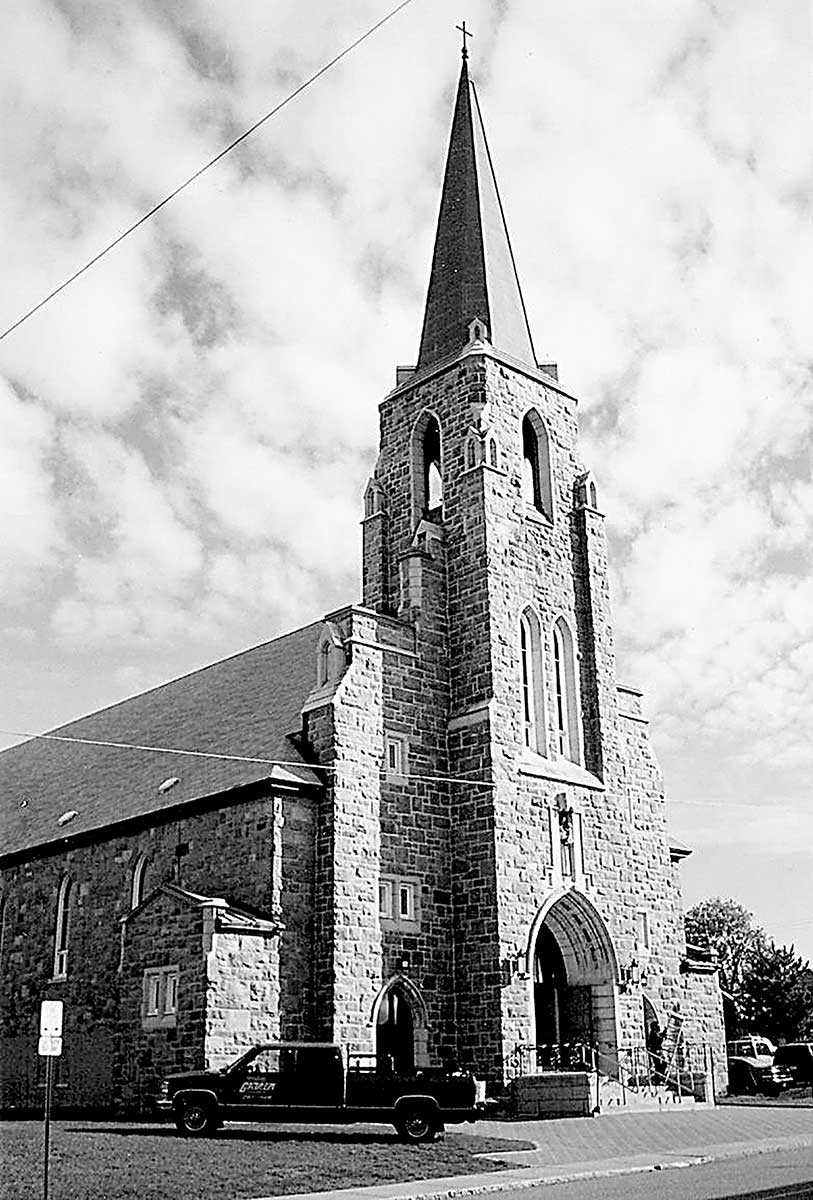

The Catholic Church played a key role in this process. In 1849, the first Bishop of Bytown (Ottawa), Monsignor Bruno Guigues, founded a settlement society and became its first president. To counteract Protestant influence, he encouraged young people from Canada East to acquire plots of land along the Ottawa River, between Rigaud and Bytown, where francophone families were already living, spread over a wide area.

Most of the new arrivals came from western Quebec, prompted by promotional campaigns there. In their minds, they were merely pushing a bit farther west to settle, as their parents and grandparents had done before them. They often moved onto poor-quality land that had been abandoned by English-speaking farmers.

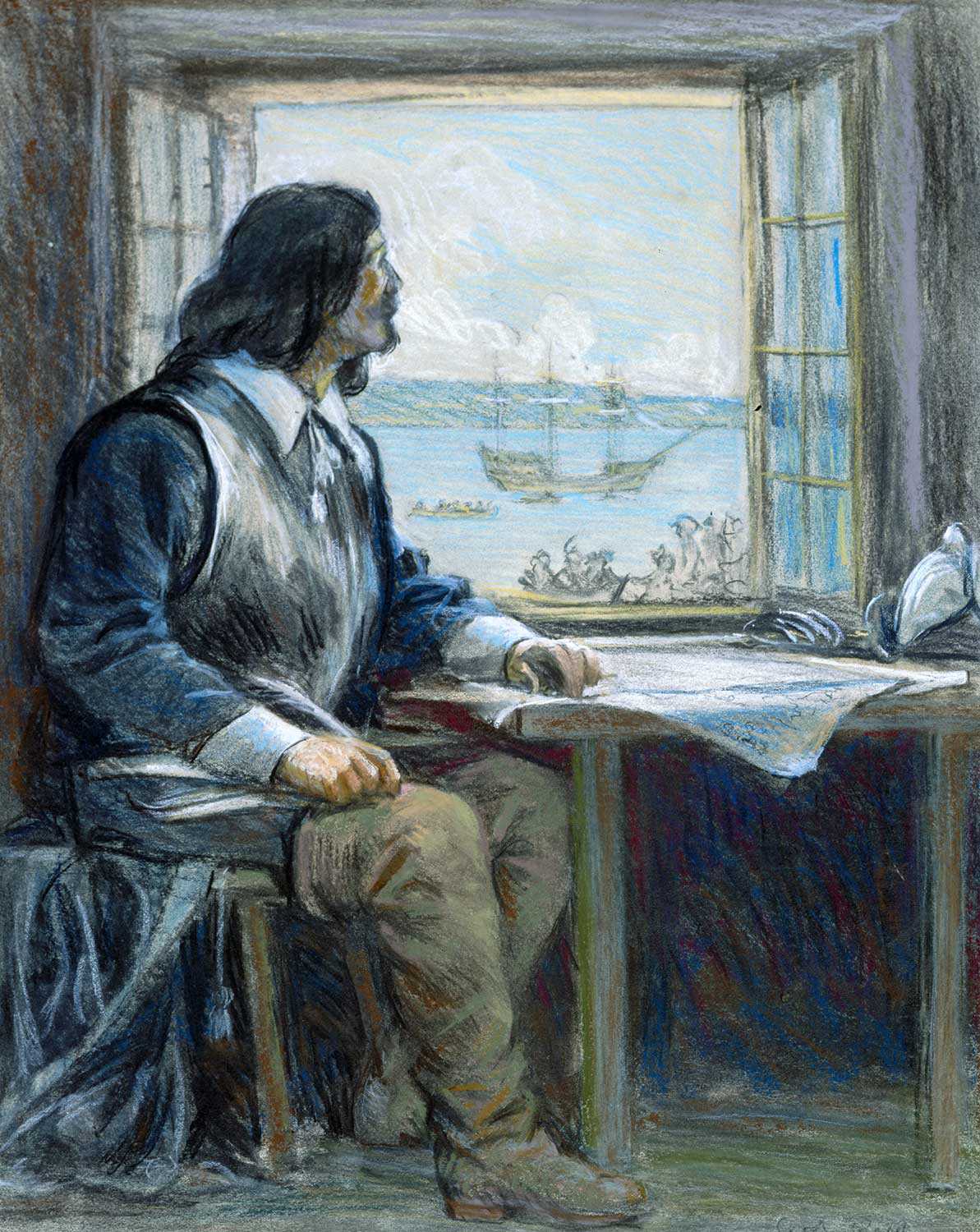

Typical scene from the early stages of a family’s life as settlers in Northern Ontario, Val Gagné, Ontario, c. 1912. Joseph Aumont, a farmer originally from the Joliette area, his wife and their three eldest children, Gabrielle, Albert and Rita; Léa and Edouard Aumont of the Ludger Aumont family; François, son of Simon Aumont. University of Ottawa Centre for Research on French Canadian Culture, TVOntario archive (C21), reproduced from the collection of Germaine Robert, Val Gagné, Ontario.

Soon, Prescott and Russell counties had francophone majorities. Arriving with little capital, the migrants could only afford small farms at first, 20 hectares on average, and the land became poorer each year under the effects of intensive exploitation. Moreover, the French-Canadian farmers in eastern Ontario did not see any advantage in owning a large plot or mechanizing their operation, since, as they had done in Quebec, they spent part of each year off their land, working in forestry to earn essential extra income. With some variations, their compatriots in southwestern Ontario and Georgian Bay were doing the same. In all three regions, the turn of the century saw a transition to the dairy industry. Still, farming for subsistence and to supply workers in the forestry industry persisted.

French Canadians were also found in the province’s industrial centres, including Toronto, where Sacré-Cœur parish had 130 families when it was founded in 1887, and Cornwall, where the migrants worked in the textile and pulp and paper industries. As for Ottawa, which became Canada’s capital in 1867 and was a small industrial centre, it attracted civil servants, professionals, craftsmen, tradesmen and labourers from the regions of Quebec City, Montreal and Trois-Rivières. By 1910, Ottawa was home to 23,000 French Canadians, representing nearly a quarter of its population.

It was in the northern part of the province, though, that the early 20th-century emergence of a French-Canadian proletariat was most pronounced – as railways were built, mines and pulp mills were established and hydro-electric power was developed. As in the province next door, the Church advocated settlement of the North, a veritable promised land. The migrants came mainly from eastern Ontario, the Montreal area and western Quebec, but there were also contingents from the lower St. Lawrence. The clay-based soils were poor, the summer short and the markets far away, and the settlers quickly reproduced a way of life based on a combination of subsistence agriculture and work in the mines and forests, or on commercial agriculture to supply the resource industry worksites. Others moved into company towns where they provided an unskilled workforce. Railways were also important employers of French Canadians. Nearly all 8,000 workers on the Canadian Pacific in the Sudbury region belonged to this group.

Thanks to these migrations and to a high birth rate, the French-Canadian population in Ontario grew from 13,969 in 1842 to 248,275 by 1921. Although they made up only 8.5 per cent of the province’s population that year, their geographic concentration made them extremely visible in certain areas. This was enough to lead some segments of the anglophone majority to raise alarms about a French Catholic invasion, which, in turn, played a large role in generating the great language conflict that shook Ontario in the first two decades of the 20th century.

![The Lamontagne family, one of many families that left Sault-Montmorency, Quebec to work at the Empire Cotton Mill in Welland. Mr. Lamontagne was the foreman of the loom tuners. Welland, Ontario [between 1918 and 1930]. University of Ottawa Centre for Research on French Canadian Culture, TVOntario archive (C21), reproduced from the Lamontagne collection, Welland, Ontario.](https://www.heritage-matters.ca/uploads/Articles/Frenette-Ph23-W9-web.jpg)

Photo: The Lamontagne family, one of many families that left Sault-Montmorency, Quebec to work at the Empire Cotton Mill in Welland. Mr. Lamontagne was the foreman of the loom tuners. Welland, Ontario [between 1918 and 1930]. University of Ottawa Centre for Research on French Canadian Culture, TVOntario archive (C21), reproduced from the Lamontagne collection, Welland, Ontario.

Photo: William Franche seated on a horse-drawn reaper, commonly called “le moulin à foin” (the hay mill) in Wendover, Ontario, 1913. University of Ottawa Centre for Research on French Canadian Culture, La Ste-Famille (Holy Family) Cultural Centre Collection (C80), reproduced from the collection of Rose Demers, Wendover, Ontario.

![The family of Simon Aumont. Only Simon himself and Irène (seated, holding a doll), survived the great fire that devastated the region in 1916, Val Gagné (Ontario), [before 1916]. University of Ottawa Centre for Research on French Canadian Culture, TVOntario archive (C21), reproduced from the collection of Germaine Robert, Val Gagné, Ontario.](https://www.heritage-matters.ca/uploads/Articles/Frenette-Ph23-VG-3-web.jpg)

![Students demonstrating against Regulation 17 outside Brébeuf School on Anglesea Square in Ottawa’s Lowertown, in late January or early February, 1916 / [Le Droit, Ottawa]. University of Ottawa, Association canadienne-française de l’Ontario archive (C2), Ph2-142a.](https://www.heritage-matters.ca/uploads/Articles/Cecillon-Ph2-142a-web.jpg)