Browse by category

- Adaptive reuse

- Archaeology

- Arts and creativity

- Black heritage

- Buildings and architecture

- Communication

- Community

- Cultural landscapes

- Cultural objects

- Design

- Economics of heritage

- Environment

- Expanding the narrative

- Food

- Francophone heritage

- Indigenous heritage

- Intangible heritage

- Medical heritage

- Military heritage

- MyOntario

- Natural heritage

- Sport heritage

- Tools for conservation

- Women's heritage

Challenges of archaeological collections management

While buildings are among the most visible elements of heritage landscapes, they are frequently like the tip of the proverbial iceberg, associated with vast underground archaeological deposits capable of fleshing out cultural history narratives – of both pre-contact aboriginal and post-contact Euro-Canadian occupations – in substantial detail through their careful investigation.

The task of curating these finds is fulfilled by over 450 consulting archaeologists licensed under the Ontario Heritage Act by the Ministry of Tourism, Culture and Sport. The ministry assists both public- and private-sector land developers in meeting their various statutory obligations to steward the province’s archaeological heritage. Annually, this work results in the registration of hundreds of new archaeological sites that span the 12,000 years of human occupation in Ontario and the recovery of thousands of artifacts in the course of archaeological surveys, site assessments and salvage excavations of threatened sites.

Artifacts (clockwise from top left): Hand-wrought and machine cut nails, screws and a spike, window glass from a Euro-Canadian homestead, carbonized corn cobs from a pre-contact village site, pre-contact ceramic potsherds, and pre-contact flint debitage produced during the production of chipped stone tools.

Since the enactment of the Ontario Heritage Act in 1975 and the development of the archaeological heritage management industry since the 1980s, it is estimated that Ontario’s archaeologists are the custodians of artifact collections that would fill approximately 25,000 cardboard banker’s boxes, enough to cover – when laid side by side – about half of a professional soccer pitch. This repository does not include the vast archaeological collections previously acquired in the 19th and 20th centuries and already curated by museums, universities and other public institutions across the province, which may well comprise enough to cover the other half of that soccer pitch.

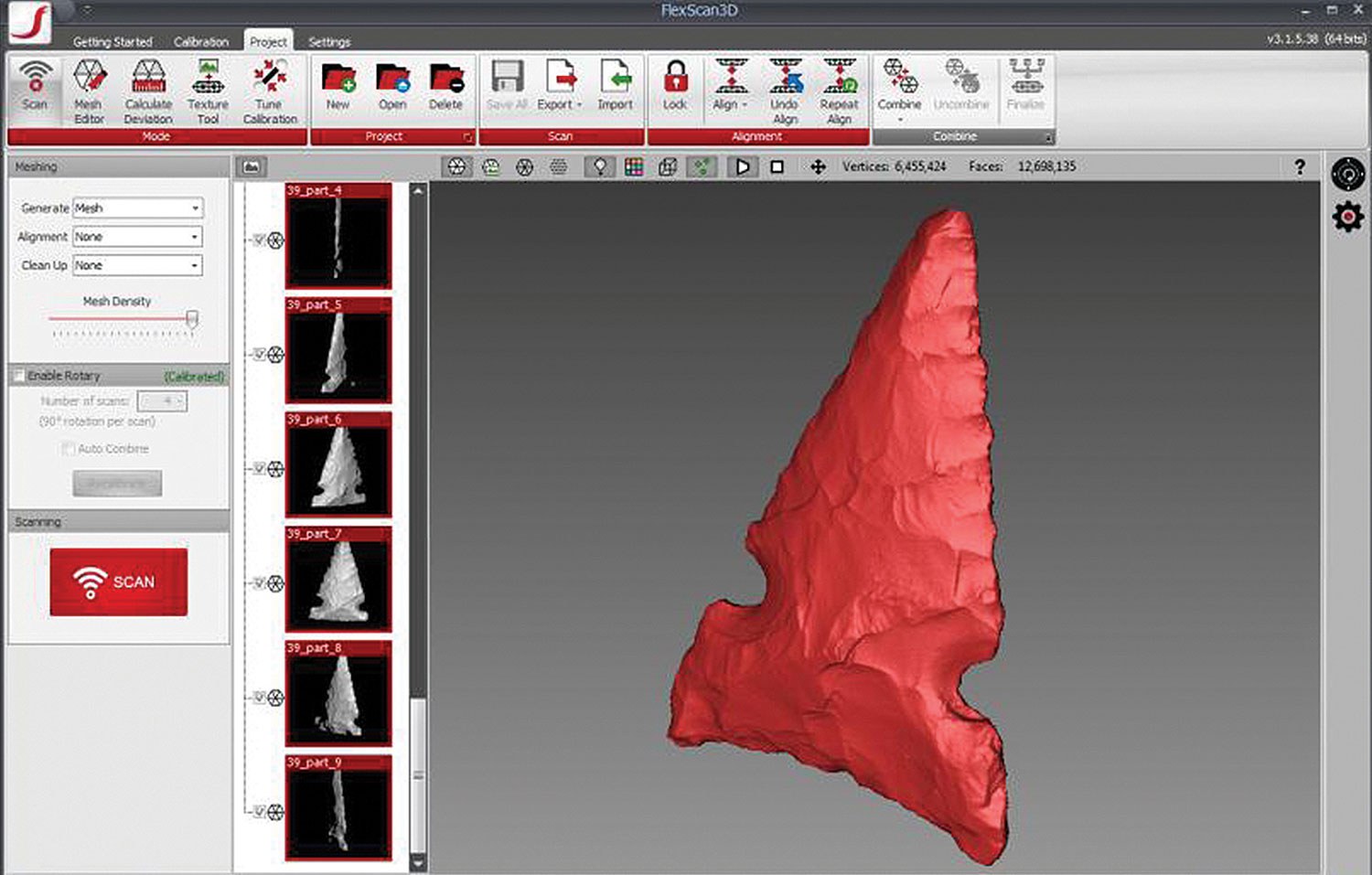

While this wealth of artifacts may seem like a boon to museums, the reality is that only a fraction of the artifacts recovered through archaeology will ever find their way into public exhibits – likely less than one in 100,000 – as the majority of artifacts are not considered to be exhibit-worthy because they are deemed too pedestrian (e.g., window glass, iron nails, flint chips, etc.), lack integrity (e.g., small potsherds), are fragile or require specialized conservation treatment (e.g., carbonized floral remains) or are redundant when compared to exemplary pieces already on display (e.g., spear points and arrowheads). With space increasingly at a premium, museums and universities have necessarily become selective with respect to the archaeological collections they are willing or able to accommodate.

This problem is not unique to Ontario or even Canada, as the growing problem of collections management has become an issue of concern worldwide wherever archaeological heritage management has been developed as an important feature of maturing societies.

In Ontario, a longer-term solution has been developed by a collaborative initiative between Western University and McMaster University with funding from both the federal and provincial governments.

With a collective storage capacity large enough to house the equivalent of approximately 80,000 banker’s boxes of artifacts, the Sustainable Archaeology project aims to work with the archaeological community, descendant communities and the public to ensure access to collections and dissemination of knowledge arising from their ongoing study. In so doing, Sustainable Archaeology seems to offer an excellent alternative to traditional museums, although certainly not the only alternative. For example, some First Nations are considering the establishment of similar facilities that might better serve the interests of their own communities with respect to the stewardship of culturally relevant archaeological collections.

Licensed archaeologists across the province manage the collections arising from their archaeological investigation, including artifact cleaning, cataloguing, analysis, conservation, curation and interpretation. This will continue to be important work along with addressing the ongoing collections management challenges that face all archaeologists throughout Ontario. [Images courtesy of Archaeological Services Inc.]