Browse by category

- Adaptive reuse

- Archaeology

- Arts and creativity

- Black heritage

- Buildings and architecture

- Communication

- Community

- Cultural landscapes

- Cultural objects

- Design

- Economics of heritage

- Environment

- Expanding the narrative

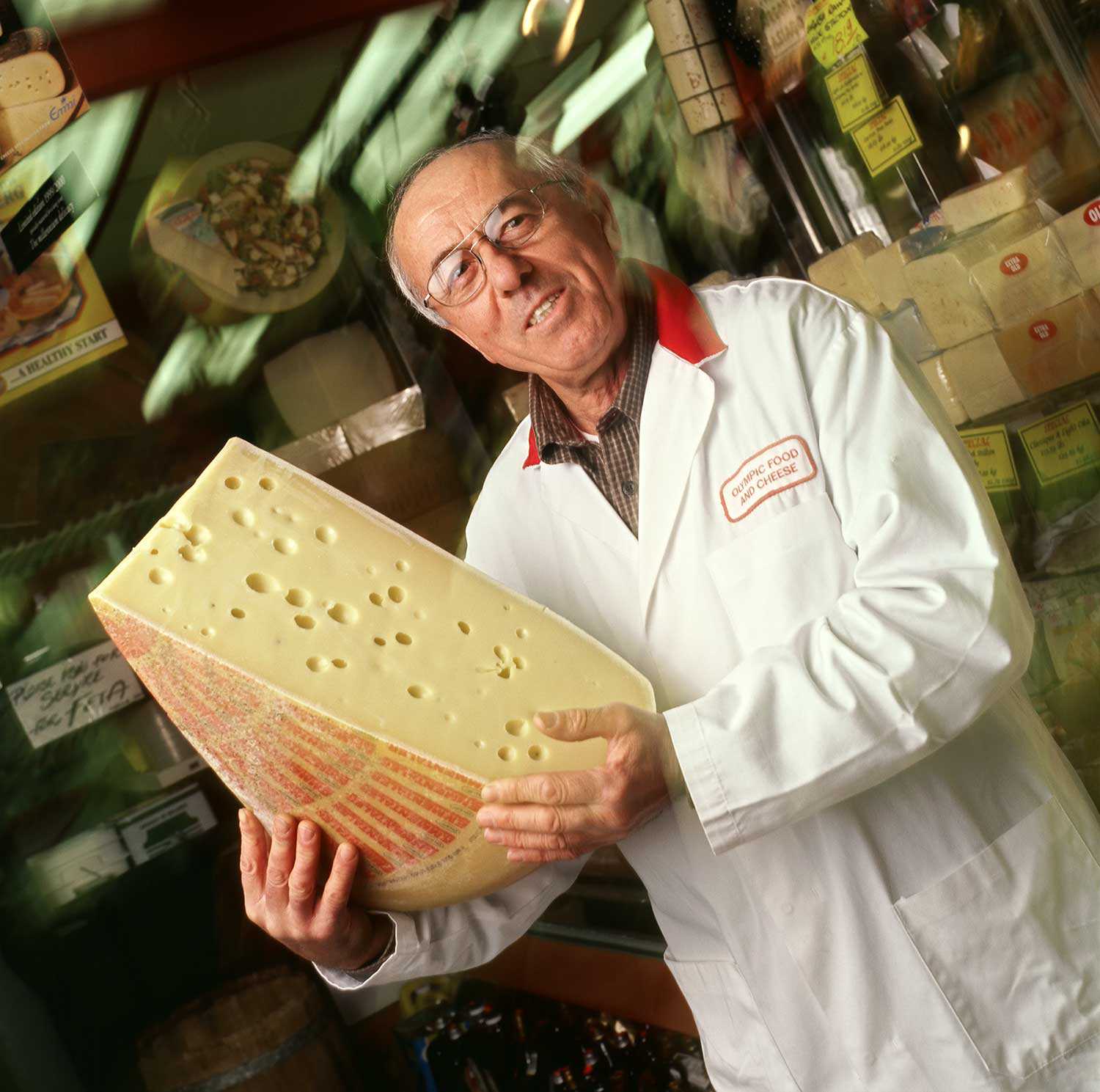

- Food

- Francophone heritage

- Indigenous heritage

- Intangible heritage

- Medical heritage

- Military heritage

- MyOntario

- Natural heritage

- Sport heritage

- Tools for conservation

- Women's heritage

Biodiversity in Ontario: Taking up the challenge

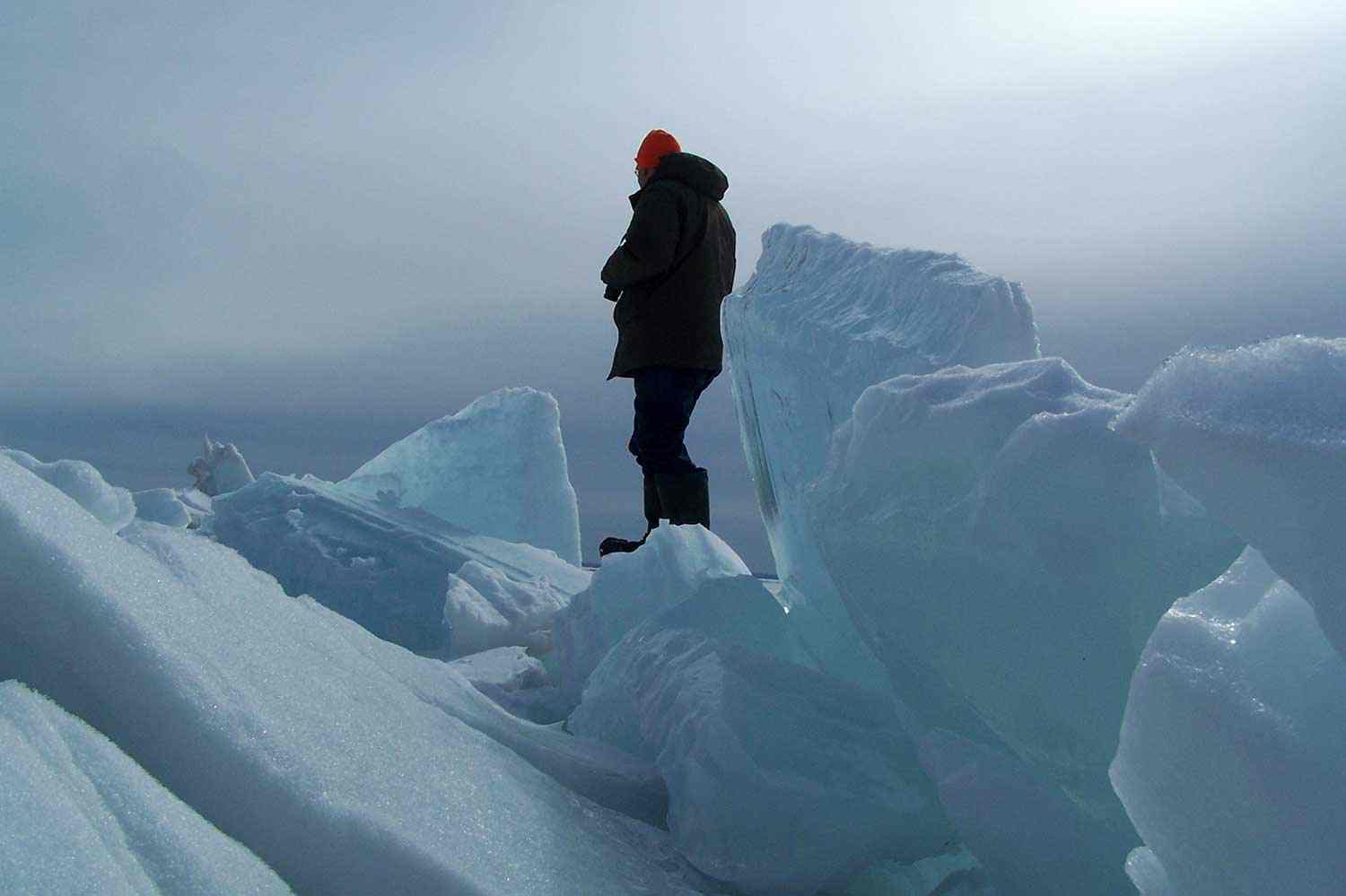

Many are familiar with high-profile threatened species such as polar bears, whose habitat is in flux and whose numbers are dropping, or bald eagles, once in danger of disappearing completely from the Great Lakes region, now recovering slowly, but still a species of special concern in northern and southern Ontario. These are only two of the hundreds of species at risk in this province.

Maintaining a large number of species with a variety of genes in a diverse environment is at the heart of the concept of biodiversity. Although the concept may sound complex, it isn’t. It simply refers to the full range of genes, species and ecosystems in a given area. Living systems depend on and thrive on each other’s existence. Consequently, biodiversity is often used as an indicator for the health of a natural area. If you remove one element or introduce a new one, the effects are often impossible to predict.

A large patch of garlic mustard (Alliaria petiolata) – one of the most widespread invasive plants in southern Ontario – at the Trust’s Willoughby property.

Species extinction over the history of life on Earth has been seen as a natural phenomenon. But the current rate of species loss, occurring within our own lifespan, is outpacing the rate that previously occurred over a geological epoch. How many species can the world lose at this rate before the ability of the environment to support human life is affected irrevocably? Have we reached a tipping point that marks the beginning of an exponential increase in the rate of extinction? Will change be sudden – a series of catastrophic losses – or gradual – or both? What is clear is that invasive species and monocultures introduced by humans are on the rise, natural habitats are rapidly being replaced by a man-made environment and biodiversity is eroding dramatically.

The more biodiverse an ecosystem, the more resilient it is to drought, flood, disease and other natural catastrophes that occur in regular cycles. In light of more rapid climate change and the accelerating destruction of wildlife habitats, the loss of biodiversity threatens the ability of the natural environment to adapt. This loss affects humans as well. We rely on the various natural systems for our survival as a species. Our economies, food supplies, natural resources, clean air and water are drawn from these systems. Their health is our health. This is as true for Ontarians as for the rest of the world. Educating the public about the importance of biodiversity and the history and impact of invasive species are new priorities for the Ontario Heritage Trust.

Pioneering American ecologist Raymond Dasmann (1921-2002) is credited by some for coining the term “biological diversity” in the late 1960s, but American Robert E. Jenkins of The Nature Conservancy may have been the first to use the contraction biodiversity and to bring the issue, in the 1980s, to the attention of the emerging conservation community. Jenkins and his peers postulated that a large number of species were in decline due to human alteration of the environment and the rapid spread of invasive species. In the years that followed, the international scientific community focused on measuring the scale and rate of loss and the significance of the problem. International attention grew to the point that, in 1992, 159 nations ratified the United Nations-initiated Convention on Biological Diversity. Canada, an original signatory to the convention, together with the provinces, identified the most crucial invasive alien species in this country and, in 2004, developed a strategy to combat the spread of these species. In 2005, Ontario, through its Ministry of Natural Resources and the Ontario Biodiversity Council, adopted a biodiversity strategy.

Notwithstanding these efforts, scientists today believe that biodiversity is in crisis around the world. Conservation experts – including Gord Miller, the Environmental Commissioner of Ontario – have pointed out that Ontario has its share of problems. There are 28 species of reptiles (nine turtles, 18 snakes and one lizard) that call Ontario home – 19 of which are now at risk. The loss of a few turtles and snakes may not register on the minds of most Ontarians as a significant problem but, to quote from the 1995 Canadian Biodiversity Strategy, “business-as-usual is not an acceptable option.”

This year, in conjunction with the International Year of Biodiversity, the Ontario Biodiversity Council released two reports on the state of biodiversity in the province. These reports paint a good-news/bad-news scenario.

To learn about species at risk in Ontario, see the inventory of species at risk on the Ontario Ministry of the Environment, Conservation and Parks website.

On the negative side, the pressures on biodiversity in Ontario continue to increase, largely due to the growth of our population. We are consuming more resources and generating more waste. According to The State of Ontario’s Biodiversity 2010 (released in May), Ontario’s ecological footprint is one of the largest in the world. In other words, the report says, if everyone in the world lived as we do in Ontario, four planets would be needed to sustain humanity.

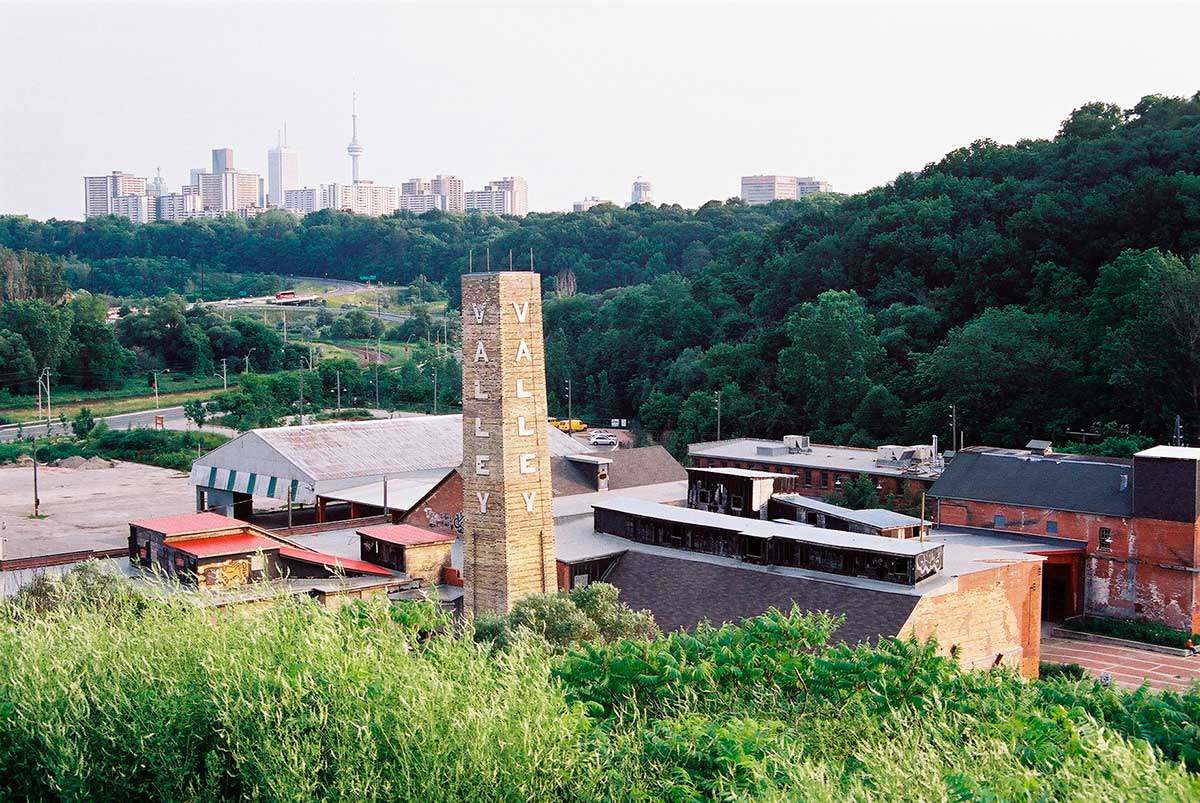

Of particular concern is the southern part of the province, where we are exceeding nature’s ability to replenish itself. This region boasts the greatest diversity of species in Ontario, but it includes most of Ontario’s human population and the infrastructure necessary to support that population. Not surprisingly, it also has the greatest number of species at risk, many of which are incompatible with human activity. Even more alarming are the indications that our efforts to protect biodiversity are producing inconsistent results – there is improvement or stability in some areas, but deterioration in most of the other species at risk.

As noted, the report offers good news too. Activities related to conservation and the sustainable use of renewable resources are resulting in meaningful improvements. Overall, Ontarians care about conservation and sustainable-use initiatives. The government is doing its part with efforts such as the Provincial Policy Statement (2005), Greenbelt Act (2005), the Places to Grow Act (2005), the Endangered Species Act (2007), the 50 Million Tree Program in partnership with Trees Ontario (2008) and promises to protect more than 225,000 square kilometres of the northern boreal region (2008). Ontario also has strong environmental organizations, an engaged and caring rural community and a growing desire by business and industry to reduce adverse effects of their activities on the environment and engage in proactive conservation and sustainable land management.

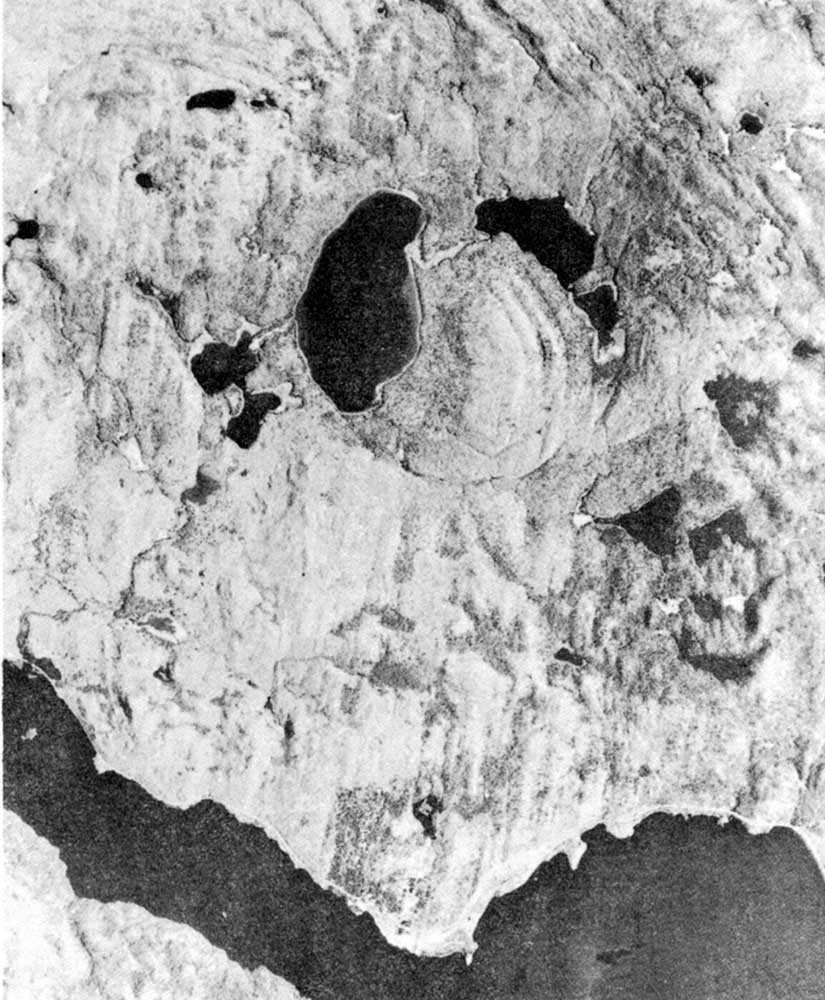

Clearly, more needs to be done. We must understand that the biodiversity crisis is entirely the result of human action. Humans have introduced some exotic plants and animals into Ontario intentionally, for esthetic, economic and sometimes scientific reasons. Garlic mustard, one of the most widespread invasive plants in southern Ontario, was introduced to the province in the late 19th century as an edible green. Bighead carp, a potential threat to the Great Lakes because of their large size, rapid rate of reproduction and hearty appetite, were brought from Asia for use in the aquaculture industry. The introduction of some invasive species has been accidental. Zebra mussels filter out nearly all the phytoplankton and can effectively starve native larva and small fish populations in lakes and rivers. These invasive mollusks were released into the Great Lakes by foreign freighters dumping their bilge water. Additionally, Asian long-horned beetles, which pose a serious threat to Ontario’s trees, were imported in the infested wood of packing crates entering North America from Asia.

The Trust works with its partners both to plant native species on the Trust’s heritage properties and conservation easement sites as well as educate the stewards, owners and other partners – as well as the general public – on this stewardship practice. It’s important that all Ontario residents learn how to identify and control invasive non-native plant and animal species.

All of us – government, environmental groups, business, industry and citizens – must work to reduce the pressures on our natural heritage and protect what we have today so that it will be with us tomorrow. Awareness and education are the first steps. Ontario has identified the issue, developed a biodiversity strategy and has issued its first report card (Ontario’s Biodiversity Strategy Progress Report 2005-2010). Whether or not we can improve our grade – while there is still time to act – is the challenge.

For more information on biodiversity in Ontario, visit the Ontario Biodiversity Council's website.

An invasive species is a plant or animal not native to a region that has been introduced by intentional or accidental human actions. It is so successful in its new range that it dominates the naturally occurring species to such a degree that it establishes a monoculture, thus greatly reducing the region’s biodiversity. For more information about invasive species, visit the International Union for Conservation of Nature Global Invasive Species Database and the Ontario Invasive Plant Council.