Browse by category

- Adaptive reuse

- Archaeology

- Arts and creativity

- Black heritage

- Buildings and architecture

- Communication

- Community

- Cultural landscapes

- Cultural objects

- Design

- Economics of heritage

- Environment

- Expanding the narrative

- Food

- Francophone heritage

- Indigenous heritage

- Intangible heritage

- Medical heritage

- Military heritage

- MyOntario

- Natural heritage

- Sport heritage

- Tools for conservation

- Women's heritage

An interview with Laura Brandon

Recently, the Ontario Heritage Trust spoke with Laura Brandon, the Acting Director of Research at the Canadian War Museum in Ottawa, to examine the role played by war art and artists in reporting the impact of the events in Europe during the First World War.

Ontario Heritage Trust: What was Ontario like on the eve of the First World War?

Laura Brandon: Essentially the province was divided between urban and rural. In Ontario, the urban focus was Toronto. Three-quarters of the population was British in origin. Fifty percent of the Canadian Expeditionary Force was born in Britain. The population in general considered themselves British and were British subjects (of course, with some noted exceptions). Obviously, the ethnic mix in Ontario was far wider. But, in terms of governance, Ontarians were British subjects.

OHT: What was Ontario’s place within the British Empire?

LB: In essence, Ontario was seen as part of Canada, so the external understanding of Ontario was that it was Canada. But there was no doubt that the two provinces that were perhaps more significant in terms of mother country knowledge were British Columbia and Ontario; they were clearly seen as the most loyal.

But, in terms of the war itself, Ontario was very important – recognized or not outside of the bigger picture of Canada. Ontario was undoubtedly the industrial hub of the Canadian war effort, producing at least one-quarter of the ammunition used by British forces overseas. It was a major fundraising hub – an astounding fundraising hub, in fact – raising half of the amount of money the Canadian Patriotic Fund allocated to soldiers and their families – and roughly half of the war bonds issued by the government between 1917-18. So, in other words, Ontario was a province deeply committed at many levels. In terms of recruitment, too, hundreds of thousands of Ontarians enlisted. It’s hard to be precise about the numbers because many people from across Canada enlisted in Ontario. But the sign-up rate was huge. Ontario was very much involved in the First World War.

OHT: What makes images so powerful? How was the war represented for the average Ontarian both on the home front and overseas?

LB: It is always hard to differentiate between public art and private art. One of the things I recently discovered as a result of a project that was undertaken by Jonathan Vance at the University of Western Ontario (he was looking at the people who enlisted in the Canadian Expeditionary Force) was the remarkably high number of people involved in the visual arts. A century later, we are reminded of what the world was like pre-photography through art.

Photography did exist – it just wasn’t as widespread, as ubiquitous as it is now. You look at the enlistment papers and you see graphic artists, architects, sculptors, art students, poster painters, sign painters and designers – the whole gamut. The Canadian Expeditionary Force (CEF) itself was visually talented in sometimes unrecognized ways. So, if the CEF had visual skills, you can pretty well guarantee that the general population was also attuned to understanding world events and their context through visual means.

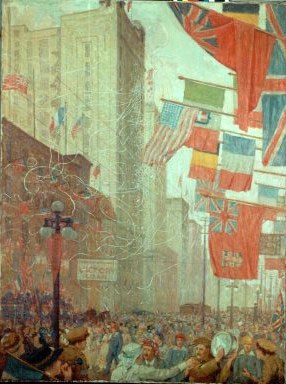

The way you initially saw art after the war broke out was through recruiting posters, which were visually strong images of soldiers and the need for soldiers, and also through posters that touted the need for fundraising and for funding the war effort. These were the kinds of images that Canadians, and Ontarians in particular, were seeing in their newspapers, journals and magazines. It was gradually understood that official art was a good thing.

The direct correlation between the fundraising and recruitment was that images and official art were organized and run by the same institutions, the same authorities. Art was intended to be permanent, while the posters and ephemera were not. The art that was commissioned for the war was intended for a memorial art gallery in Ottawa where future Canadians could come to learn what the First World War was all about.

So, that’s one side of it: the public side of visual arts. The private side used the talents of all of those visual artists who were actually in the war. Collectively referred to as “soldier art,” this art includes the work of often well-known artists who also became solders in the First World War (e.g., Group of Seven member A.Y. Jackson). But soldier art also includes work by people no one had ever heard of.

Some of the research I’ve been doing has been to try and find out what the relationship was between public and private art. I started on the assumption that there would be a difference. Those people who were directly involved in the conflict would see it differently from those who were commissioned to paint large canvasses commemorating certain important events, particularly battles. And I’ve tried to discover that the war culture of official artists (who were producing public art) and soldier artists (who were producing art that they popped in envelopes and sent home to their families) were affected by the same culture. When it came to things like battles and death, neither the public nor the private artist wanted to depict it and preferred to use symbolic or emblematic language, showing sunsets and sunrises or a blasted tree to suggest that something terrible had happened. By exploring the art of the time, we can see how all-encompassing the war effort was between 1914-18 and what a huge impact it had on the social fabric of its time. It crept into every nook and cranny.

That leads me to your first question: What makes images so powerful. Ultimately, it comes down to response. Human beings have always been visual. Widespread literacy is a relatively recent phenomenon in most cultures. Even in the mid-19th century, Ontario’s literacy rates wouldn’t have been outstanding. It’s really a Victorian achievement that had very little impact until the last 200 years. Before that, people learned visually; we’re wired to understand the world visually. For that reason, images – whether on posters or postcards, in magazines or newspapers, whether photographed, painted or silkscreened – continue to make huge impact.

I’ve often said that, in a way, war art is akin to religious art in its impact. If you look at medieval cathedrals, for example, and their use of visuals to get across ideas about Christianity, those same methodologies – established even earlier, in the times of the Greeks and Romans – are the same when it comes to the 20th century and the First World War. It’s part of who we are as humans that we recognize art as something that can have an impact. Knowing how to understand it and how to read it makes an enormous difference, too.

OHT: What was the specific function or role of the war artist?

LB: As I mentioned before, there’s more than one kind of war artist. There’s the official war artist and there’s the unofficial one, generally called the soldier artist. The intentions of what they were doing were completely different.

The official artists created massive canvasses designed for a war memorial art gallery that was ultimately never built – it was supposed to be where the National Gallery stands in Ottawa today. The intention there was purely historical. The Canadian War Memorial Fund that had created this organization was spearheaded by a remarkable Canadian, born in Ontario, named Lord Beaverbrook. He had been much influenced by what he saw when he arrived in Britain – history being conveyed in a stately British home by staircases decorated with portraits, in massive palaces with massive battle paintings. In other words, he was impacted by the way history could be captured for all time in major canvasses.

Beaverbrook believed that this could be done for Canada, too. He organized the program to reconstitute the First World War in art for the Canadian population for time immemorial. His initial idea was to have approximately 40 large-scale paintings that would show the work of the CEF throughout the First World War, from beginning to end; these paintings were intended to go around a dome. To get an idea of what it would have looked like, you’d have to look at the inside of the Senate Chamber on Parliament Hill in Ottawa, where eight of these paintings have hung since 1921 – massive eight-foot by 12-foot canvasses. This program was created by the authorities, so when we call it an “official” war art program, the word “official” refers to the fact that this art is visual art that encapsulates to some degree what the significance of the First World War was for the authorities as opposed to particular individuals and how they wanted it to be remembered.

Private art, on the other hand, had a completely different function. It was the kind of art that was sent home to families. It’s much more about what the war experience was like at a personal level. Most of this art has, until relatively recently, disappeared into archives because it’s not big and impressive and doesn’t involve lots of famous artists.

Yet much of it is incredibly emotive. I’m thinking of one piece that we hope to exhibit soon. It’s only about two inches high by seven inches wide and it depicts a poppy field. It’s a beautiful landscape from the First World War, which doesn’t carry any overt messaging about what was achieved on a particular day or why an event was significant. It’s just a soldier responding to some moment of beauty that he found in the midst of war. That, to me, is the important part of this private art – it gives you another dimension to the public view of the war, which is of a sequence of events, important for the nation, that does not allow for these private moments when there might be a moment of joy or pleasure or sorrow. And it adds to the complexity of war art as a whole, and captures the experience of the war in a much more multifaceted way than official art could do.

OHT: How does art uniquely convey or capture the experience of war?

LB: I’ve concentrated on what I believe the art does. But, I’ve left out the viewer – an important part of the equation. We discovered that when we put on an exhibition a number of years ago at the Art Gallery of Ontario called Canvas of War (organized chronologically to encompass the First and Second World wars). This exhibit was driven by a historical trajectory that explained why Canadians fought in the wars, what was achieved and who was involved. But, when we showed the same exhibit in Gatineau at the Museum of Civilization, we had comments from hundreds of thousands of visitors after seeing these paintings about what they felt about war. Those comments weren’t about how they felt about history or about the Canadian contribution. They were about how the visitors felt personally.

So, although war art – both public and private – can share a purpose that the artist determines it should have, the audience (its visitors, its viewers) doesn’t necessarily pay attention to that aspect. Artworks create their own meaning and have their own meaning, which is unique to each person looking at them.

In recent years, war art along with war memorials have been described in terms that use the words “sites of memory.” In my opinion, the war art collection as a whole, when it’s on view in public and also when people are able to see it in storage as well, acts as a site of memory to which people bring their knowledge, their own personal memories. Then, they can engage almost in a conversation with the work of art to reflect on war, their own experiences and their own thoughts about it.

OHT: Was the First World War the first conflict to generate such a broad and busy visual culture?

LB: There have always been war artists, perhaps not always at the front lines. Artists have always commented on war. Spanish artist Francisco Goya commented on a war in Spain that took place at the end of the 18th, beginning of the 19th centuries. Another artist named Jacques Callot made prints that criticized the conduct of the Thirty Years War, which occurred in the 17th century.

It was only in the mid-19th century that photography enabled people to understand the brutal reality of the American Civil War. Images from that war – and there were millions of photographs from that conflict – were published in journals across the United States, bringing the conflict into the homes of American citizens. So, war has been described in visual terms probably back to the time of cave dwellers. It’s just part of our culture as human beings.

But the difference with the First World War is that it was so massive. We can talk about Canadian war art, we can talk about war art by Ontario artists, but every nation involved in the First World War across the globe had some kind of visual art program or visual artists engaged in creating works for art. I believe that the extensive presence of art is unique to the First World War because it was such a massive, industrialized war involving millions of people. So, in that respect, the art of the First World War had such a significant impact because it had a global impact.

OHT: Have perceptions and representations of the First World War changed over the past century?

LB: People still paint scenes from the First World War. As time goes by, however, different forms of knowledge come into play, different social contexts, different cultures. And that affects the lens through which we look at something from the past.

One of the things, for example, that surprised people about Canadian First World War art is how few paintings have poppies in them, given that the poppy is now so closely associated with the First World War. Although that in and of itself is interesting, the other thing that’s interesting is that the First World War also acted as a sort of corrective to perceptions that crept into what the First World War was like. Many people, for example, understand it through photography, which is largely black and white. So, when they think of the First World War, it’s in black, white and grey – rather grim colours to represent a rather grim time. On the other hand, the Canadian War Museum has sketches in the Beaverbrook collection of war art that are brightly coloured with vivid blue skies and fluffy white clouds. They provide evidence of a much more complicated visual imagery of war and the theatres of war.

One of the things that remains really important when thinking about war art as a whole, as well as its representations and the way it’s perceived, is that you have to look at all of it to understand what life was really like a century ago and accept the fact that, over time, different aspects are more in focus than others. For example, 100 years ago, there was probably little interest in identifying artworks that had women in them because the First World War was primarily seen as a male endeavour. In today’s society, more effort would be made to ensure that any artworks or photographs from that era that showed women were identified to try and redress that marginalization in the First World War effort.

Furthermore, when we talk about war art, we discuss the concept of remembering and forgetting. It’s this coming into and going out of focus of different aspects of something that was documented a hundred years ago that colours our understanding of this conflict at different times. What matters in one decade doesn’t necessarily matter in another. But, at the end of the day, what was created a century ago in the form of art matters today because it directly relates to that time, tells you about it and helps you understand different perspectives of the same war.

For example, we have the biggest war painting ever created for Canada, which is 40 feet wide by 12 feet high, by British artist Augustus John. He never finished it. It’s a curious work because when you look at it, you see that he’s put a bunch of Canadian soldiers and horses in a French landscape with ruined castles and the local populous, carts, women with head scarves and children running around. I look at this piece and think that it’s a very strange way for one of the most important First World War artworks to commemorate the war from a Canadian perspective. When you look at it, it’s so European, so British. What a weird way to commemorate the First World War and have that as the centrepiece of your memorial art gallery. But you have to go back a hundred years and remember that at the beginning of the war, Canadians were British subjects. This kind of European view of the First World War wasn’t that strange to them – it was familiar, within a generation.

It’s important to remember and that’s what the art helps us to do. It helps us to look at a moment in time 100 years ago, to understand that moment in time, and gives us the opportunity to reflect on it 100 years later.

OHT: Is there anything else that you would like to add in terms of your own thoughts or interests?

LB: I think it’s important to recognize that an enormous number of Ontario artists created artworks – both officially and unofficially – because of those enlistment numbers; people might be interested in that. People may also be interested to know that they can look at this art and aspect of the First World War on the Canadian War Museum’s website. There are a number of resources there that can help expand on some of the things I’ve already mentioned.

![J.E. Sampson. Archives of Ontario War Poster Collection [between 1914 and 1918]. (Archives of Ontario, C 233-2-1-0-296).](https://www.heritage-matters.ca/uploads/Articles/Victory-Bonds-cover-image-AO-web.jpg)