Browse by category

- Adaptive reuse

- Archaeology

- Arts and creativity

- Black heritage

- Buildings and architecture

- Communication

- Community

- Cultural landscapes

- Cultural objects

- Design

- Economics of heritage

- Environment

- Expanding the narrative

- Food

- Francophone heritage

- Indigenous heritage

- Intangible heritage

- Medical heritage

- Military heritage

- MyOntario

- Natural heritage

- Sport heritage

- Tools for conservation

- Women's heritage

A night out at the Gardens

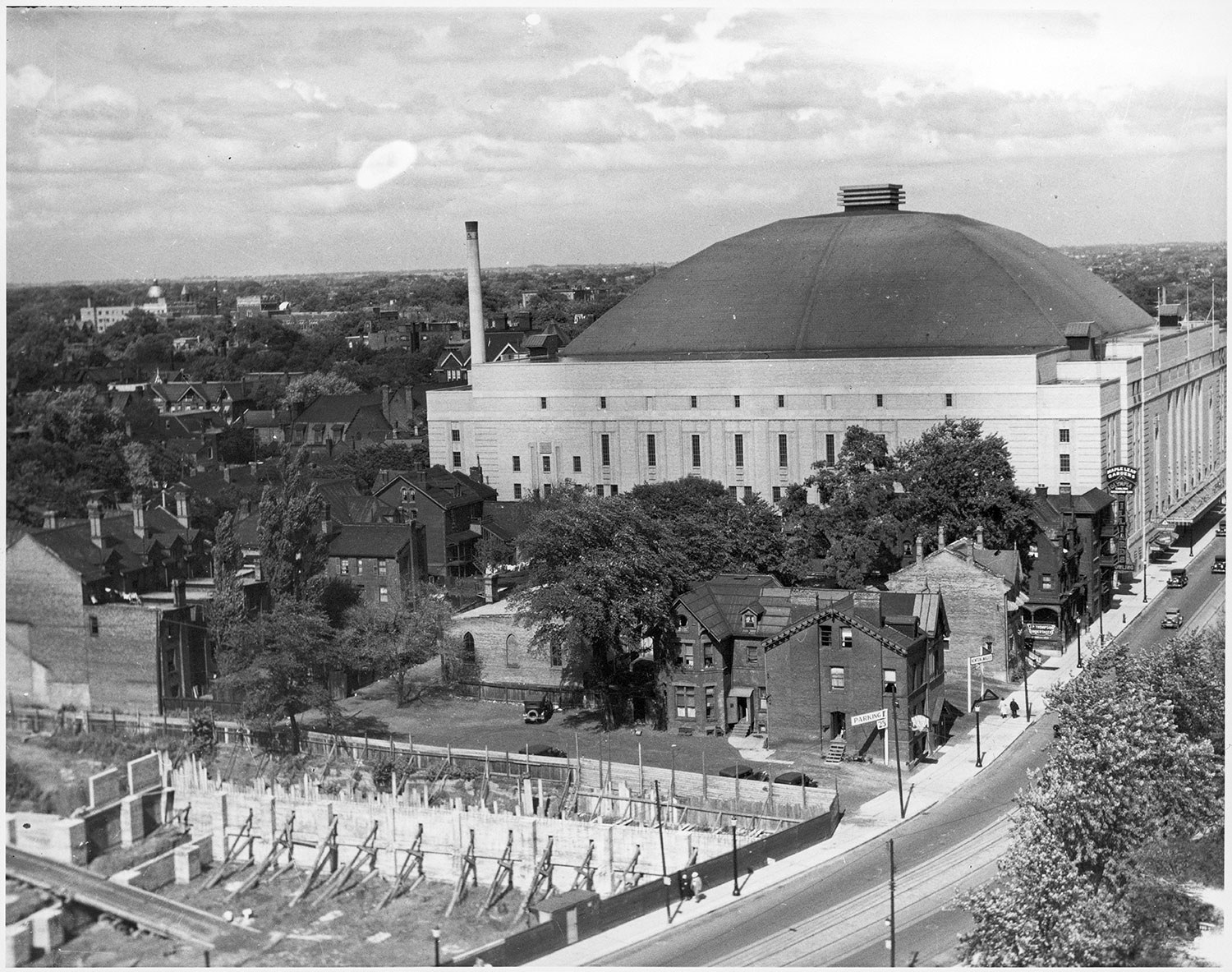

Before the opening of the now-iconic Maple Leaf Gardens, the hockey team after whom the building was named played its games in Arena Gardens. Also known locally as the Mutual Street Arena, Arena Gardens was the National Hockey League’s (NHL) largest arena until 1923. Opened in December 1912, Ontario’s first artificial ice rink had, according to the Toronto Daily Star, “room for 2,000 skaters and 7,000 spectators.” Typical of arenas built in this era when facilities were intended as much for recreational community use as spectator sports, the Arena Gardens set aside Friday nights for public skating.

At the time, what was referred to as senior amateur hockey was as popular a spectator event as the emerging professional game, if not more so. But by 1930, the situation had reversed itself and the local team, now named the Maple Leafs, was being run by Conn Smythe, owner of a local gravel business.

Smythe would recall that, at Arena Gardens in 1930, “about half the time we were packing in 9,000 counting standees, but still weren’t grossing enough to pay our players what they could have been getting with the richer teams in the US.” It was this example of United Statesbased teams who were playing in new, larger facilities – such as New York City’s Madison Square Garden and the cavernous Chicago Stadium – that compelled Smythe to build a new hockey arena in Toronto. By owning the arena, he would not only control its use, but also retain all of the ticket and concession revenues.

Cultural and economic circumstances were markedly different for commercial hockey in Toronto just two decades after Arena Gardens’ opening, and public skating was not a feature of the arenas of the 1920s-30s. The defining feature of these new sporting palaces was that, above all, they catered to spectators interested in spending disposable income on watching sporting events.

The experience of the hockey spectator (indeed any spectator) in the 1920s and 1930s did not occur within a vacuum, but among an increasing array of consumption possibilities. Accordingly, the building of Maple Leaf Gardens is best understood not solely in terms of developments in professional hockey and the NHL, but alongside the construction of other major sites of public consumption in interwar Toronto – including theatres and cinemas for the new talking motion pictures, public entertainment spaces such as Sunnyside Bathing Pavilion and Maple Leaf Stadium (built for baseball), renovations to the Royal Ontario Museum and construction of Eaton’s College Street store in 1930.

To compete in the burgeoning entertainment economy of the late 1920s, entrepreneurs envisioned sport spaces that would exclude – or at least be seen to attempt to exclude – disreputable elements such as gambling and instead project an aura of middle-class respectability. In Toronto, this meant locating the new arena in the neighbourhood of another civic institution that was wooing the respectable middle-class consumer, Eaton’s College Street department store, which owned the land on which Maple Leaf Gardens would eventually be built.

Smythe opted for the same architectural firm, Ross and Macdonald, which had designed Eaton’s flagship store. Their architects created Toronto’s largest indoor gathering space, one that supported the Maple Leafs’ efforts to gentrify the practice of sport spectating without eliminating the possibility of distinctions within the arena. The nature of the seating, for example, was increasingly less comfortable as one travelled higher in the arena, and the building was designed to prevent spectators from moving between the different tiers of seats.

It was into this environment that Smythe hoped to attract his preferred respectable middle-class spectator, a spectator who was likely male, but who would feel that Maple Leaf Gardens offered sufficient comfort to bring a female companion. But, in light of these expectations, who from among Toronto’s population of more than 600,000 citizens opted to spend their evenings attending hockey games? An analysis of ticket subscription records from the mid-1930s reveals that Maple Leaf Gardens indeed attracted middle-class men and women.

But while Smythe was more interested in gentrifying the practice of watching hockey rather than the game itself, the presence of a middle-class audience does not imply that its members spectated in “respectable” ways. The spectator experience cannot be easily distilled to a single experience. Indeed, it was a pastiche of different experiences. Certainly, many spectators took pleasure in the spectacle that unfolded on the ice surface before them, both in the speed of the game and its (oftentimes violent) physicality. But it was not the spectacle alone that attracted the spectator. The opportunity to share the experience with others was also important.

The fact that the average ticket subscriber purchased slightly more than two tickets suggests that attending hockey games was a social experience. This held true regardless of social standing, although in Maple Leaf Gardens’ expensive box seats, subscribers were more likely to have purchased numerous tickets and host a group of spectators. In the less expensive seats, it was more common to find spectators with a connection to one another – for instance, neighbours or co-workers – who individually purchased adjacent seats. Former spectators recall the ways in which hockey spectating was a social occasion: a parent taking a child to his/her first game, a couple going on a date, as well as couples attending in groups.

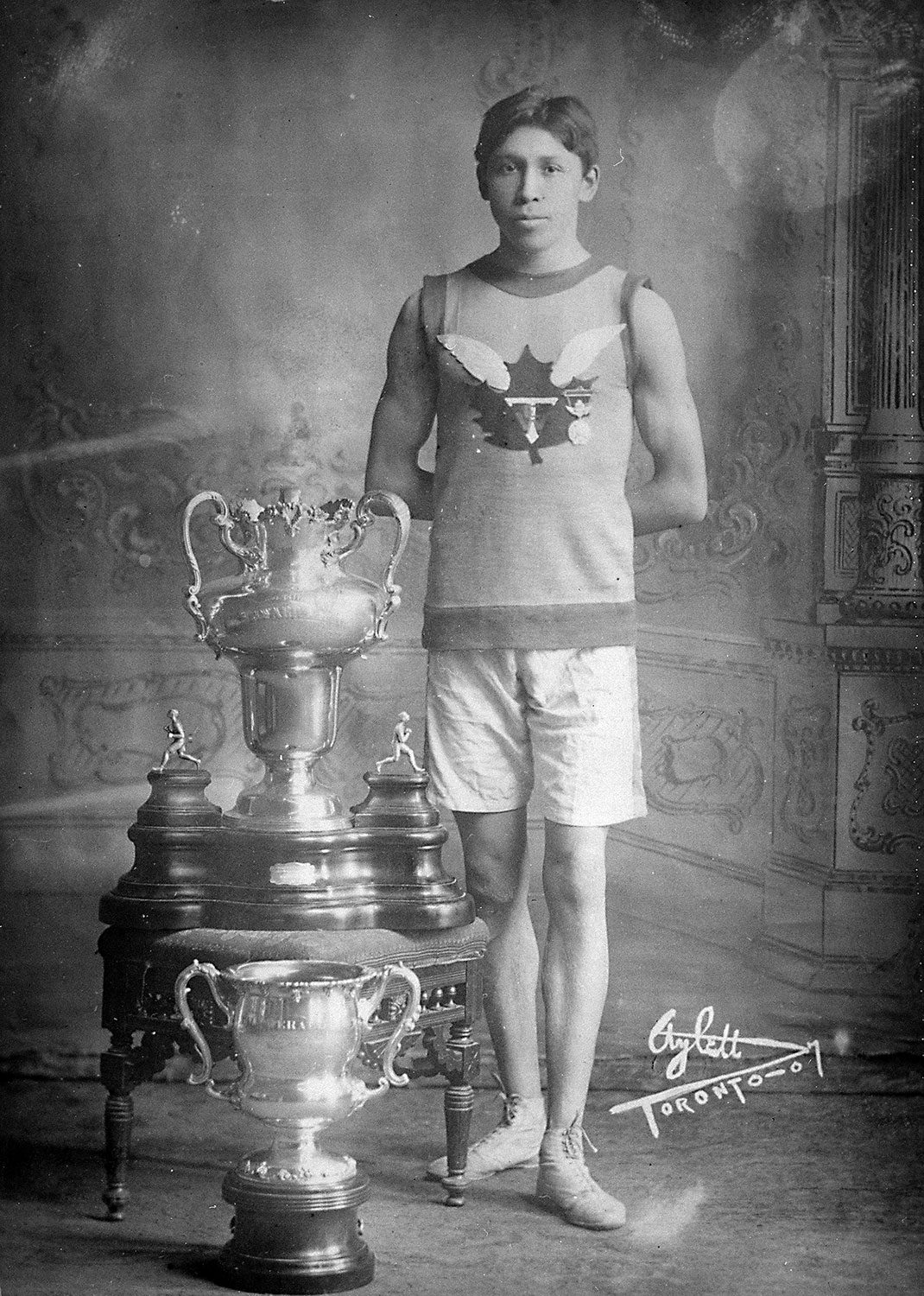

Perhaps most interestingly, while many women entered the arena accompanied by men, there were women who went to hockey games in the company of other women. One female spectator recalled how she and five companions, all female, went to professional hockey games in Toronto every Saturday from 1925 to 1931. This dedicated group began spectating prior to the opening of Maple Leaf Gardens, but with the construction of this modern, new arena, their weekly outings took on the air of an occasion as the sextet dressed in their finest each Saturday night. This woman, whose grandson recounted her story, recalled the “fashion show in the stands” where she and her friends sat in Maple Leaf Gardens’ grey seats, the cheapest seats, most distant from the ice. While elite hockey spectating has its origins as a male pastime in the new spaces of sport in the interwar years, women increasingly attended games and enjoyed themselves and spent their disposable income at Canada’s most prominent sport venue.